|

Lois Greene Stone, writer and poet, has been syndicated worldwide. Poetry and personal essays have been included in hard & softcover book anthologies. Collections of her personal items/ photos/ memorabilia are in major museums including twelve different divisions of The Smithsonian. The Smithsonian selected her photo to represent all teens from a specific decade. BIRDS"What a great July 4th day." I squeezed my father's hand hardly aware of the moisture coming from his skin. "Soon I will be teenage! And no more ration books because of a stupid war: 1946 is swell."

"Glad, honey." My dad looked uneasy. "Why are you nervous, Daddy?" I questioned. Propellor blades rotated quickly and the airplane climbed higher. I wasn't aware that this was the first airplane for commercial use since World War II ended, and that the cabin was not pressurized. My father clutched the armrest and forced a smile. "Look, Daddy!" I poked him. "We're going on top of the clouds." I pushed my face against the tiny window and tried to see La Guardia Airport and familiar Flushing Bay below. "This is a dream. Cotton balls. Clouds look like cotton balls." "More like whipped cream," My father commented as clouds peaked and seemed suspended. Blue was above, but next to and below was only white to gray fluff. "My ears still hurt." "Chew the chicklets, Lois." "They still hurt. But I love this," I said with wonder. "But you don't seem to like it." "I like it, but it's a little scary. Clouds seem thick, dense, like bumping into any will be like hitting a hard object. I didn't grow up with airplanes, honey, but am happy that you are." He looked in the seat pocket to be sure the motion-sickness bag was available in case he got sick to his stomach. The pressure in his head couldn't be relieved by chewing. He definitely liked trains better. "Remember how long it took us by train, Daddy?" "Hm." "Stop joking." "Four hours to Washington, DC. And we ate in the dining car and looked at beautiful fields pass before the big windows. The coffee came in silvery pitchers, and all the tables had starched white linen cloths. But this is the future, and you should feel comfortable with it." I had the feeling that my father really wished he was going from New York to Washington by Pullman and spending four hours hearing metal wheels pass over metal tracks. "But we'll save hours this way and..." I looked back in the tiny aisle and saw a hostess serving lunch. I stood up and the seat cushion's scratchy fabric brushed coarsely against my legs. "It's half a sandwich and fruit. Isn't that swell?" "Uh, huh." My father glanced backwards. I didn't know then that the clouds under the plane as far out and down as he could see made him queasy, or that it felt, to him, unnatural. I didn't realize that he was frightened, or heavier than air machines were unheard of when he was a boy. I didn't understand that he'd only had a car since 1938 and he thought that was amazing. And he got Mom a machine that washed clothes automatically in 1939. I never knew what it was before cars or washers. "Look what Mom's missing!" The stewardess handed me the small lunch. "Why'd she take the train?" Popping relieved pressure for an instant, then my dad's ears clogged again. "No, thanks," he refused the food being offered. I didn't know then that he was protecting me from the concept that life is fragile, precious, filled with accident and also pain. As a pre-teen, I thought I was immortal and guaranteed to be free from harm. He camouflaged emotions that might have exposed that he was frightened about crashing, or upset about traveling in an upside-down situation where overhead sky was below, or in pain from almost unbearable pressure in his ears. He and Mom had silently decided a father must present a strong and fearless image as a role-model. Dad answered, "She'd had a cold, remember?" "Uh, huh," I bit into the soft bread with a slice of turkey between it. The action of my jaw caused an intense pop in my ears. "Well, the doctor told her she couldn't fly after a head cold." My father tried to sound convincing. "But she had a mustard plaster so I thought it was her chest not head." I brushed a bread crumb from my lap to the floor. "She didn't want you to miss this." My dad leaned toward me. "We'll see her later with your sisters at the hotel." "Oh isn't life something." I strained and looked at the plane's wing. "Oh. There's a patch of ground. Look. Look. I'm going to do this forever. Trains are boring and take too long. This is..." I grabbed my father's arm. "See the ground? There." My dad showed pleasure with my enthusiasm. I didn't know that having clouds under him was like his childhood image of heaven, and heaven had to do with death. He covered his fear as much as he could; he never said that one day I'd probably feel as he did about something and he hoped I'd give my own children freedom to believe in an eternal safe future. "Nothing will ever be as swell. Wish Mom didn't have to miss this. Daddy. We're going down. Back to earth. We're like birds." The stewardess removed the lunch tray. She brought another packet of two teeth-shaped, white-coated pieces of chewing gum. I thought he was whistling very, very quietly. I didn't hear his prayer to let us get down safely, and take care of his loved ones. And it never crossed my mind that the family intentionally split up for travel; in case of an accident, the whole family wouldn't be wiped out. Aloud he said, "Chew. It'll help your ears. Flying is your future. Life is incredible. We people can be birds." "And," I quipped, "some people have bird-brains." I began to hum, then pressed my nose into the window watching earth come up. There was never an opportunity to thank my parents for the gift of innocence and adventure; my father died before I was fully grown. I live 400 miles from Flushing Bay, yet I can never fly into La Guardia without thinking about that first flight, and, with amazement, that it happened so many decades ago. My youngest decided he'd try skydiving. How could I shake my uneasiness about his attempting to become a bird? Suppose his harness fails, his arms tire, he heads into a mountain? Suppose ... a bird...why can't he take a plane! I suddenly remembered my special air trip in an unpressurized cabin sitting beside my father. I imitated my dad, pretended not to worry, silently prayed, and aloud expressed "Life is incredible." Published 1999 Rochester Shorts reprinted: 2003 Heroes from Hackland

0 Comments

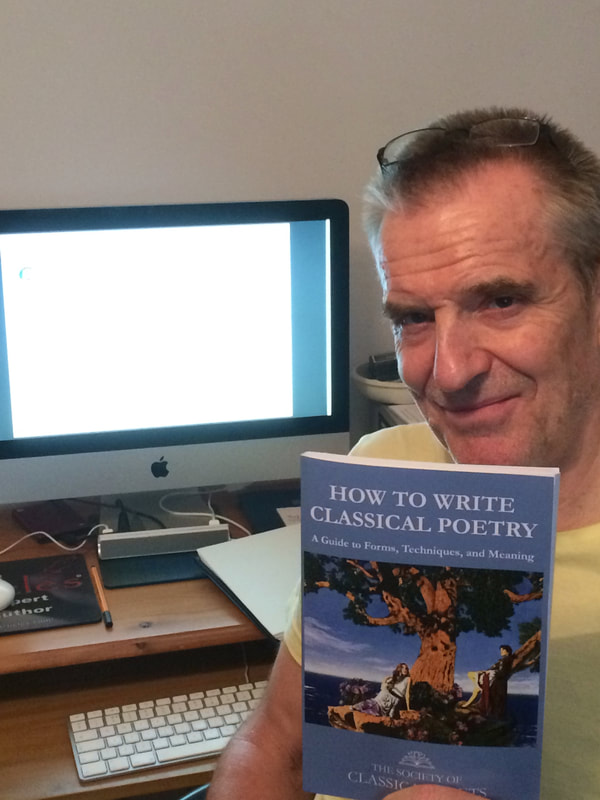

Carol Smallwood is a literary reader, judge, and interviewer. Her most recent book is Visits and Other Passages (Finishing Line Press, 2019). Interview of James Sale December 1, 2018 Lowestoft Chronicle http://lowestoftchronicle.com/issues/issue36/jamessaleinterviewbycarolsmallwood/ Interview of James Sale

As well as being a management leader and the creator of Motivational Maps, which operates in 14 countries, James Sale has published 8 collections of poetry and also books on teaching the writing of poetry. His poems have appeared in many UK magazines as well as the United States: he was the winner of The Society of Classical Poets Poetry prize for 2017, and winner of their Prose prize for 2018. James has been a writer for over 50 years, and has had over 40 books published. Specifically, on the teaching of poetry his titles include: The Poetry Show volumes 1, 2, 3 (Macmillan/Nelson), Macbeth, Six Women Poets (Pearson/York Notes), as well as titles from major publishers such as Hodder & Stoughton, Longmans, Folens, and Stanley Thornes. https://www.amazon.com/James-Sale/e/B0034OVZ5I/ref=sr_tc_2_0?qid=1537138136&sr=1-2-ent Smallwood: When did you begin writing poetry and who are a few of your favorite poets? As for many others, at puberty – 14 – when the Muse visited me for the first time, and for the first time I heard a poem being read aloud and was astonished by it. I immediately thought: “I must do that” and I did. I was in Mr. N. A. Thomas’s English lesson at the time. Aside from the greats, who are in another class – Homer, Dante, Shakespeare and Milton – the lyric poets I especially love are Herbert, Rochester, Coleridge, Keats, GM Hopkins, and Yeats. Of contemporaries (since poetry did not stop with the birth of my mother, and although I completely disagree with his underlying, atheistical philosophy), Tony Harrison is a force to be reckoned with; and I am on record at the The Society of Classical Poets’ website for claiming that your own Professor Joseph Salemi is a major poet, though his Muse – one of savage satire – is not my preferred style now. That said, when I was younger, Rochester, a vicious satirist, pleased me greatly. I delude myself into thinking I am more kindly now. Smallwood: Do you think being involved in management motivation relates to your literary writing? That is an interesting question, and the answer has to be yes, because everything is connected. When one looks back on the arc of one’s life – and truly begins to understand it – all is incredible and all is a miracle; indeed, a miracle of ‘rare device’. You may remember the actor David Carradine who starred in the Kung Fu series. He memorably said: “If you cannot be a poet, be the poem.” The poet makes a poem; and we make our lives. If we have not made our lives, then we are already dead; but the strange thing is – there is another force influencing our lives in exactly the same way that the Muse starts to write our poetry. And like the Muse there is an unpredictability about it – about God basically. Those with no Muse in their lives or poetry must suffer their fate; those whom the Muse/the God speaks to, encounter their destiny. How it affects my writing would, alas, take an essay to explain, so I’ll move on for now! Smallwood: What is your most recent poetry collection, Inside the Whale, about? Actually, Inside the Whale is my penultimate collection. The Lyre Speaks True is my most recent book. But there are no accidents and as you have nominated Inside the Whale, then let me talk about it. This collection is a metaphor for being in hospital – as Jonah was swallowed whole by the whale for 3 days and nights, so I in 2011 suddenly collapsed and found myself in hospital for 3 months. Unbeknown to me I had a malignant cancer, one of them the size of a grapefruit inside me. After two major operations, and one near-death experience, I finally emerged from hospital into the light, into the land of the living, an ‘older, wiser man’, and one, like Jonah, transformed by the extremity of my experience – and the saving grace of God that brought me back when I was nearly dead. The poems detail some of my experiences in this inferno. Perhaps, if I may be permitted to quote from one short one, your readers will get a flavor: I Heard the Lord I heard the angel, I heard the Lord – Dying, and his word came to me. Lying there, in that dumb sweat, no word Expressing what it was not to be. Confessing only in my tear, torn eye: What was the soul able and full of? Not – whatever men think, contrariwise, This earth of nothing, this lack of love With condemnation’s fearful, fevered pitch! No, I say, I heard the Lord. Go, he said, rise up and touch – And as I did – life struck its chord. Smallwood: One of your books (I was pleased to note) is Six Women Poets: please share who they are and how you selected them? Yes, the Six Women Poets are all popular British poets who are on UK examination board syllabuses; in other words, they are studied in UK schools by 15-16 year olds for exam purposes. I was asked, therefore, specifically to write review notes on these poets and their poems to help students pass their examinations; so, I did not get to choose them! The six are: Gillian Clarke (currently the Poet Laureate of Wales), Grace Nicols (a Caribbean poet who emigrated to the UK in 1977), Fleur Adcock (actually born in New Zealand, but perhaps the most classical of them all), Carol Rumens (greatly influenced by Plath and Sexton, and the American women poets generally), Selima Hill (a poet focusing on personal experience and its meanings), and Liz Lochhead (who was the National Poet of Scotland). A diverse group, representing a lot of diversity in the UK. One final comment, though, would be to say to all poets, male and female, if you want more sales of your poetry collections, then make sure you get on an exam syllabus somewhere! Smallwood: What is the Royal Society of Arts and how did you get elected a Fellow? I was a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts (FRSA) for 10 years, but resigned my fellowship a couple of years ago for reasons I will come to. But the full title of the RSA is: The Royal Society of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, which gives a slightly different nuance to its focus. It was founded in 1754 – before even the American Republic existed – and it was a child of the Enlightenment. What Enlightenment really means, of course, is secularism, humanism, atheism. It’s quite masked; many religious types belong to the RSA and see no problem, but I increasingly found myself irked by the heresy the ‘enlightenment’ always presumes: namely, the Pelagian heresy. In short, the RSA subscribes to the view that society and human beings are perfectible – they are busy creating a brave new world, and in my view now this is all utopianism, which will fail. Putting this in a ‘classical’ framework: we need to improve the world and use all our strength to do so, but to think we can do this without or in defiance of the gods is what the Greeks called hubris. And there is so much of that about. But thank you for reminding me: there are still places up with my name framed with FRSA, which I need to take down. How did I get in in the first place? My good business friend, Tim Bullock, an investment ace, was a Fellow and proposed me: so, you see, there is an example of the business and the art world mixing. Currently, I am member of another London club (but with overseas links to other worldwide and in places such as New York, which I am visiting next year): The Royal Over-Seas League. That suits me better. Smallwood: What is The Society of Classical Poets and what prizes did you receive from them? Can anyone submit poetry? I love The Society of Classical Poets and everything about the organization and its inspirational leader, Evan Mantyk - with the possible exception of the rancor of some of its members! It exists to promote real poetry: that is to say, poetry with form, for without form there can be no poetry. Poetry is form. It is true, in case there are any doctrinaire free-versers reading this, that occasionally, a true poem exists that seemingly is ‘free’, but this is an extreme exception; and it is a not a starting point. The idea that someone who can’t write a coherent sentence is somehow a poet because they splash words on a page is part of a profound and immoral political agenda. People easily forget that the greatest modernist – and free-verser – of the C20th, TS Eliot, didn’t really write ‘free’ verse: a cursory study of the Wasteland reveals iambics everywhere, and rhyme as a matter of course. It seems to be the view that has taken hold that writing in conventional forms means one is ‘conventional’ – as if that were a bad thing. The overemphasis on the individual at the expense of society is one reason why the West is rotting internally. The Society of Classical Poets is seeking to reverse this in its domain of poetry. So anyone can submit a poem, but it is pointless submitting ‘free verse’ and post-modernist claptrap. Alongside the insistence on form is the requirement of beauty – poems should be beautiful even when dealing with ugly subject matter. Take Wilfred Owen: his poems on Word War 1 create a terrible and terrifying beauty. There is nothing sentimental or sloppy there about using form. As for prizes, I am proud to say I won Second Prize in their 2015 Poetry; First Prize in their 2017 Poetry competition; and I have also won First Prize in their 2018 Prose Competition for my 4-part series of Muse articles, which I recommend to anyone wanting to know more about poetry and its true origins. Past winners are not considered a second time, so I encourage all your readers to enter this year’s competition – it’s free to enter. Smallwood: Please tell readers about the Cantos you are writing. What is terza rima and why did you chose it? I found the form very challenging to write and cannot imagine a sequence: Thank you for this question. Ultimately, true poets want to be challenged by the biggest mountain they think they can climb. Of the 9 Muses, Calliope is the Muse of epic poetry, and since I encountered Milton in my early 20s and his Paradise Lost blew my mind, I have wanted to write an epic. However, as I have experimented with blank verse I have found it impossible to attain the gravity that epic demands. As Keats found, with his two Hyperion fragments (awesome as they both are), one ends up sounding like sub-Milton. Recently, I started re-reading Dante’s Divine Comedy; also I went to Ravenna to visit his grave. And it all clicked: the terza rima form was underused in the English language (Shelley being the best exponent of it in his unfinished The Triumph of Life), it was ideal for narrative, and I had been to hell in hospital, had had a near death experience and been taken out of the body to another place and experienced the divine, and what with some other matters as well, I reached the conviction that I could write a psychological divine comedy in English – the English Cantos – modelled on Dante, in which I visit hell, purgatory and heaven, but perhaps in a more restrained 33 Cantos. I have written nearly six of these now, and the first three have appeared on the Society of Classical Poets website. I’d appreciate any of your readers visiting, reading and commenting on my work: http://classicalpoets.org/canto-1-by-james-sale/ http://classicalpoets.org/canto-2-by-james-sale/ http://classicalpoets.org/canto-3-by-james-sale/ There is also a dramatic YouTube reading by my youngest son, Joseph Sale, (a fabulous novelist actually - published by a New York press: see The Darkest Touch) of part of Canto 1. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nbex5IGecZw&feature=em-share_video_user It is extremely difficult to write in terza rima partly because the English language is poor in rhymes compared with Italian. Dorothy L Sayers did a masterful translation in the 1950s, and Peter Dale did a good one in the 1990s. But many translations stick to prose or blank verse, or variant rhyming: I love the new translation by Clive James, which is not terza rima, but does use rhyme. He has some wonderful and idiomatic turns of phrase. For example, one of the counterfeiters in hell (keep in mind that counterfeiters produce the ‘not’ real thing) says: ‘In Hell everything is real’. Wow! How well my use of the form stands up only your readers can judge; but for myself so far I am pleased with what I have done, and I think the whole thing makes for a gripping read. The thing is: terza rima is ideal for narrative: the interlocking rhymes propel the story sense forward. Whereas, for example, Spenserian stanzas do not. James has a poetry website at http://jamessalepoetry.webs.com and a personal website at www.jamessale.co.uk Carol Smallwood is a multi-Pushcart nominee; she’s founded, supports humane societies, serves as judge and reader for magazines; a recent poetry collection is In the Measuring (Shanti Arts, 2018). Lois Greene Stone, writer and poet, has been syndicated worldwide. Poetry and personal essays have been included in hard & softcover book anthologies. Collections of her personal items/ photos/ memorabilia are in major museums including twelve different divisions of The Smithsonian. The Smithsonian selected her photo to represent all teens from a specific decade. Sorority Rush week. Rush, to me, once was the caning of seats in a trolley car. Rush meant in-a-hurry. As an undergrad, it concerned sororities.

That time span, that was later defined as the "Happy Days" generation, was post-World War II and the then-ongoing Korean War. It was commonplace to “rush” as these organizations would allow members to be with other girls of the same religion and present an opportunity to mingle with fraternity males also of the same denomination. I attended the party of the two possible places that I could join, and found the first friendly, but full of forced-smiles and a promotional atmosphere that spoke of why it was better than its competitor. I then went to the next and the members seemed to come from a cookie-cutter which had replicated one individual as they were a blurred group of co-eds with the same hairstyle, pleated skirts that appeared to be an unofficial uniform, and facial makeup to cover post-adolescent acne. Then I was quite literally told that if I pledged, I was not to then, nor ever, date men who were not in its brother fraternity. With never any more make up than a pale pink lipstick and straight natural blonde hair that required me sleeping in metal rollers (before hair dryers or curling irons) but was never sprayed or “perfect,” my preferring wind to blow it and rain to moisten it, the second place was no option. My philosophy was inclusion; sororities seemed to say exclusion. I did not sign up to potentially be considered a member of either. On the day the “results” came out, there were girls in my dorm literally sobbing about rejection. What was wrong about an acceptance that didn’t come? It wasn’t about the individual, but the distraught dorm-mates could not see that. We, in the dorm, were mixed religions and races; we were fine together. Yet the word “sorority” seemed to be very important to many. At a dorm meeting, I proposed that we initiate our own non-sectarian, interracial unit, and ask the school to support our idea and give us housing. Such a concept had never been realized. The university approved. We also agreed that there would be no pledging, no excluding someone by a negative vote (then called the blackball system), and any female who agreed to live with kindness and consideration with women of any religion and race would be a member; that she must agree upon before moving into the dorm. Since we couldn’t fill the space for 66 co-eds, the university housed independent women with us and many became members and wore the sorority pin. Others who were uncomfortable with our premise, say being given a roommate of a different skin color for example, moved out as soon as was possible. I hand-typed individual letters to colleges and universities across the nation; there were no computers or printers or any duplication machines except for mimeographs. I proclaimed our values with the key strokes on a Remington Rand typewriter, before electric typewriters made touching keys easier, and I naively believed this group would become a recognized national organization. I received letters from southern schools that were hateful. At my northern New England university, I had no idea that the South at that time differed regarding religious or racial tolerance. This was before integration. Other mail came back to me with "no" and statements about how the idea was quite awful, and those words surprised me from northern and mid-western places. My grandfather, a photographer who photographed U.S. Presidents from Taft through Truman, gave me an idea to telephone Eleanor Roosevelt, whom he personally knew, and she allowed my grandfather to give me her personal home phone number. I called her in New York and explained my frustration with “society,” and said maybe if she could take the train to Connecticut and meet us and speak, it might acknowledge why our concept was important. She agreed; I bought her a corsage of her favorite flower, a camellia. There were no bodyguards when she got off the train, and she ate in our dorm’s dining room, accepted an honorary pin, and I so expected society would suddenly change. Of course it didn’t. But Mrs. Roosevelt gave us reason to continue with our rebellious-for-the-time sorority house fully integrated in race and religion and we girls became adult women accepting others for their personalities and outlook—not what pews they sat in or whether their skin tones matched. Of course we all didn’t get along like some big friendship circle; we were people first, and our likes and dislikes were based on personality clashes or petty jealousies or such, but never on racial or religious differences. Rush week still happens. And girls will slump in hallways looking at rejection slips and still sob and feel despair. “Sisters” can blackball a potential pledge, and dictate to an initiate. Despite that, there are now dorms of both men and women in the same building, curfews don’t exist anymore, dress codes are obsolete, and fraternal organizations are no longer specifically for one religion—at least on paper, as far as I know. We have improved. Eleanor Roosevelt would be pleased with the 21st century’s advancements in technology and humanity. The South began integrating its schools in 1957. In 2008, the country elected a black President who held office for eight years. Our country has gone through numerous progressive movements since the 50s, and society has changed views and legislation for same-sex marriages, transgender bathrooms, and so forth. We are better than the "Happy Days" generation. I see society the way I see the change in postage stamps. We no longer have to endure the bitter taste of a postage stamp to affix to an envelope but merely press it and it adheres with ease, and the stamps are forever so a rate raise doesn’t mean extra postage to use. We all make a difference and don’t need a bitter taste of life left in our mouths to try and make something stick; with a direct, simple yet solid effort, the newly affixed stamp of belief or support can stay in place, delivering us into new territory. While none of us can live forever, I want my time to still be helping shape values that will endure. ©2017 The Write Place at the Write Time

GENDER EQUALITY: WILL THIS SOLVE ALL OUR PROBLEMS? Gender equality is a familiar phrase. It is supposed to lead the way toward a more egalitarian and fair society. However, since the 1970’s many positive changes have been made, but women are still subjected to domestic violence, rape, sexual harassment, sexual objectification and other abuses of power. The point of this article is that only the dismantling of patriarchy itself will solve our problems. This is not just a women’s issue, and it cannot be done without the full involvement of all men.

The fight for women’s rights has been waging for hundreds of years in countries around the world. The word “feminism,” meaning the advocacy of women’s rights on the ground of the equality of the sexes, became a word in in our vocabulary in 1910. Voting rights, employment equity, marriage and divorce rights, property rights…The work of a feminist (or whatever name one prefers) is never done. It seems no matter how much progress is made, women are still victims of violence, discrimination, harassment and much more. Movements (Suffrage, Women’s Lib, MeToo, etc.) can’t keep up with the ever-recurring complaints made about the lack of gender equality. From afar, it looks like just so many chickens running around with their heads cut off. Why is this such an intransigent problem, and more importantly, is gender equality the solution or just part of the problem? And does gender equality mean equality for men, too? We will get to that in a moment. As of 2016, there is no prohibition of sex discrimination in the United States Constitution, and only 22 states have their own Equal Rights Amendments. Someone doesn’t think gender equality is a good idea. Perhaps it’s because the road to gender equality has so many twists and turns. Consider Iraq. One of the purported reasons our military invaded Iraq was to rid the area of a despot, clearing the way for democracy, but what kind? Under Saddam Hussein’s secular government, women enjoyed academic freedom and were among the most advanced in the Arab world. Muslim religious leaders now control the Iraqi government, and women lost their rights under Islamic law. Sex trafficking, which was practically non-existent in Hussein’s regime, is now on the rise due to an unstable government, corruption and unchecked criminal gang activity. In Afghanistan, domestic violence, rape and forced marriages flourish. The United States military forces there have not been successful in rooting out the Taliban and other Islamic groups opposed to women’s rights in over 17 years. According to the Afghan Independence Human Rights Commission and the United Nations, at least 90% of Afghan girls could not attend classes in five southern Afghan provinces, partly because girls’ schools were being burned down. American women now fight alongside men to secure safety and security for women in the Middle East and elsewhere, but what happens to our women soldiers when they come home? According to Veterans Affairs studies, women veterans are two to four times more likely to be homeless than other women. They are nine times more likely to suffer from PTSD---and not just from combat. (15 to 23% of female veterans seeking VA services report having been sexually assaulted while on active duty. If they are expecting the military to address the issue, their superiors better not continue to enlist the likes of U.S. Air Force’s Lt. Col. Jeffrey Krusinski to lead efforts to curb sexual assault in the military. He was arrested in 2013 for groping a woman in a parking lot near the Pentagon. The Army needs to do the same. In that same year an Army sergeant instructor of sexual assault prevention was arrested for sexual assault and maltreatment of subordinates. Many women military members report that they have faced retribution and social ostracism for reporting sexual assault, but reporting rates are on the rise in spite of that.) Women vets now commit suicide at almost the same rate of male vets, a gender equality statistic few expected. For women aged 18-29, veterans kill themselves at nearly 12 times the rate of nonveterans. The equality of women, whether at home or in war, has historically been a controversial and divisive issue, and many fight against it. Aside from Tunisia constitutionally guaranteeing gender equality in 2014, the International Monetary Fund has indicated that global gender equality has stalled. Sweden ranked number one in gender equality prior to 2014, while Egypt ranks 58 out of 58 countries studied by the World Economic Forum, a Swiss nonprofit organization. (The United States ranks 17). 1 Gender equality is self-evident to some, but to others it is absurd. Despite rumors to the contrary, many women are against gender equality. Why? (1) “If I make more money than my husband, he will feel emasculated. I want him to be the man of the house.” (2) “Why should I work? I can’t get any cooperation now. Even when I’m sick I have to do everything. I wouldn’t have the energy to work a full-time job too.” (3) “The only thing I get from my marriage is the ability to not work. I’m not giving that up!” There are other reasons. As the above # 1 notes, women buy into keeping patriarchy intact. Often called male-identified, these women see other women (but not necessarily themselves) through the eyes of men who believe in patriarchy. Women are considered catty, manipulative, weak and are at fault if they are raped or abused. These women enable the current power system to prevent being ridiculed, ostracized or even murdered. Of course, we all know this doesn’t work. Striving to be sexually attractive to win approval is a no-winner, also. Beauty is no guarantee of good fortune. Remember Marilyn Monroe and Nicole Brown Simpson? Survival may not be the only reason for eschewing gender equality. Others in society feel that men and women can never be equal because it’s just not “natural.” For instance, the life expectancy gap between the sexes is seven years, the female winning. This is a phenomenon the world over; in virtually every mammal species, the female typically outlives the male. In fact, men outrank women in all of the 15 leading causes of death except one, Alzheimer’s disease. Perhaps women and men can never attain equality because of their brains. Researchers at the University of California-Irvine have found that men and women have different colored brains. Men have more gray matter which may explain why they are better at “high-end mathematical reasoning.” Women have more white matter which may explain their aptitude for recalling words, remembering landmarks and other memory abilities. In addition, women’s brains are 10% smaller than men’s, giving ammunition to those who feel women should never run the government or carry weapons. Perhaps men and women can never be equal because of differences in their hormonal makeup. Estrogen and progesterone help protect women from heart disease until menopause. After menopause, if they opt for estrogen replacement therapy, they still win, unless they suffer possible side effects associated with such treatment. Female hormonal imbalances have been used by men to keep women out of board rooms and the military: “Who wants a pre-menstrual with her hand on the nuclear button?” On the other hand, post-partum depression and PMS have been used as defenses to win mothers lighter sentences or acquittals for murdering their children. There is hormonal equality to a certain degree, however. Men can suffer from andropause, the male version of menopause. Symptoms include fatigue, hot flashes, pain and stiffness, depression, irritability, anger and reduced libido. Although more uncommon due to testicular function declining gradually in most men, should men gain or lose power as a result of such symptoms? More importantly, how can women ever be equal to men as long as they become pregnant? Some women’s rights activists don’t see how women can win equality until all babies are developed in an incubator and co-parenting is mandatory (where applicable). As long as pregnancy results in women being incapable of uninterrupted productivity, having limited physical mobility as well as being subject to hormonal disruptions, the female reproductive process will be as much a liability as an asset. In addition, pregnancy still is the scarlet letter “P.” Society will always know that a woman has had sex, a most private of acts, while the man involved can forever remain unknown or blameless, if circumstances dictate. She, on the other hand, can be subject to punishment, ridicule, family ostracism or job sanctions (legal or otherwise). She may suffer the guilt of having an abortion or medical complications from trying to end the pregnancy herself. If she hides her pregnancy and then stuffs the newborn into a dumpster, she risks legal action. How can women otherwise secure sexual equality? Women were certainly sold a bill of goods in the 1960s with the sexual liberation movement. Sexual objectification, rape, pornography, pimps and sexual slavery have not been eradicated. Women still suffer unwanted sexual advances, harassment and attack; they have increased risk for venereal disease and AIDS. They still, in ever-increasing numbers, choose to be pornographic stars, strippers and beauty queens, perhaps hoping to achieve riches or fame but too often being exploited, injured or killed. Although the question “What else can I do to get rich?” seems to be less relevant now in the age of women attorneys and corporate executives, the need to be desired by men remains, and not everyone has the brains to go to college. More opportunities in well-paid less glamorous, but safe, technical jobs need to be open to girls/women. Indeed, early feminists advocated non-sexist jobs for all. This meant more men getting into female-oriented jobs, such as nursing, for instance. However, that pesky income inequality issue never sleeps. Male registered nurses earn $5,148 more than female registered nurses. In fact, income inequality has been a reality in that field since 1988. (National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses.) Some think that income inequity starts in childhood. Several studies in America and Britain have indicated that girls get paid less allowance than boys while doing more chores. Although there has been some progress in the adult world, in this country housework is still seen as not worthy of government pension benefits. Early feminists wanted housewives to earn a yearly income, calculating the cost of such services as cleaning, child care, laundry, cooking and the like to be about $25,000 annually. Today, such combined work could be worth $45,000 or more. In spite of the fact that housework is a dead-end and volunteer job, many females are lining up for the job. A survey of teenagers in America, conducted by Families and Work Institute in 2005 found that 75% of girls said they would stop work for a while when they had children, but only 14% of the boys said the same. The newest trend is for women with college degrees to drop out of the career rat race and come home to raise their children. The big change is that many of these women have economic tools to become self-sufficient, if need be. According to the Center for Women’s Business Research, women-owned small businesses without employees are the fastest growing businesses, allowing more women to work at home while they care for their children. Mompreneurs Online and Ladies Who Launch are two resources available for these women. Some corporations are becoming more flexible in order to keep talented women’s jobs available in the future. Of course, for true gender equality men have to have the same choices. Women-owned businesses average 25% female board membership in Fortune 500 companies, and even more in those ranked 501-1,000, according to Ms. Magazine. One could question why the percentages are not more. In any case, Norway ruled that by 2008, corporations had to have 40% of women on their boards or be shut down. Norway has more than twice the number of women in its government than the United States, which could explain such legislation. However, since then, France, Spain and Germany have imposed gender quotas on corporate boards, as well. Gender pay equity is not a new loony feminist cause. In 1942, The National War Labor Board wrote: “The National War Labor Board issues General Order No.16, authorizing employers to make voluntary adjustments which equalize wage or salary rates paid to females with the rates paid to males for comparable quality and quantity of work on the same or similar operations.” 2 We’re still trying to solve this problem in 2018. In researching this complex issue, I found that, much like those who deny the Holocaust ever existed, there are those who believe women are treated fairly in the workplace. If they are not, it’s for a good reason (e.g. dangerous jobs pay more). However, a certain pay disparity remains even after factoring in such things as age, race, occupation, average hours worked, number of years in work force, dangerousness of job, region of employment and other factors. Some researchers are hesitant to claim that pure sexism explains the difference. As wages doggedly become more equal, however, corporations increasingly fight back by moving jobs overseas or employing cheap immigrant (legal or otherwise) labor. Such corporate warfare also results in men making less money, which makes the gender pay gap appear to be disappearing. Women who have fought for parity and have gained employment in the steel, automotive and aerospace industries, now find themselves being laid off “just like the big guys.” Wal-mart, the largest corporation in the world, is not a champion of women’s equality. “God made Adam first,” stated one manager as the reason.3 Women comprise 70% of the corporation’s employees. The corporation makes tremendous profits by paying women four to five percent less than their male counterparts, and women don’t make it to top management in a timely fashion either. According to Ms. Magazine, “Workers for Wal-Mart in Bangladesh make even less---13 to 17 cents per hour. It’s hard to spot male workers in the sweatshop scenes; the vast majority of this near-slave labor force is female. The women live in squalid company-owned “dorms,” sleep in crib-like bunks, wash in basins on the floor and clean their teeth with their fingers because they can’t afford toothbrushes.” 4 Although 1.5 million women joined a class-action suit against the giant retailer, the Supreme Court threw it out. Another ongoing income equity battle is being waged to raise the minimum hourly wage to $10-15. The Bureau of Labor Statistics noted that in 2014, however, that 1.7 million workers, two thirds of whom are women, were not even paid the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour. The federal government does not enforce state and local laws in such matters. Western society has suffered the growing pains of gender equality for 30 years or more, and what is the result? Indeed, more women are prime ministers, presidents and legislators. More women are in the military, media, medical, legal, law enforcement and corporate ranks. However, there are big prices to pay for being equal “in a man’s world,” as previously noted. Lung cancer is now the number one killer of women in wealthy nations. They die at a higher rate than men of cardiovascular disease, are sent to prison more often by non-sexist judges, work in polluted factories and die of occupational hazards previously reserved for men. Women are participating in (men’s) war mentality and dying on the battlefield. (Even more will die since the Pentagon opened all combat jobs to women as of 2015.) In ever increasing numbers they are media stars---this time as ninja warriors or serial killers. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health announced in 2006 that, for the first time, girls’ use of alcohol and drugs was higher than boys’ use. Such equal self-abuse is especially harmful for girls whose reproductive development can be disrupted by even moderate use of alcohol, according to Warren Seigel, president of the New York state chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics. According to ACLU statistics, the number of women in prison rose 757% from 1977-2004. (No, that’s not a misprint.) Two thirds of these women were black. The crimes ranged from prostitution, fraud and drug use. In addition, many of these women were victims of domestic violence. Gender equality may bring us other horrors. Rihab Taha, a female Iraqi microbiologist held by U.S. intelligence in Baghdad, was nicknamed “Dr.Germ” because she had been in charge of the Iraqi facility that weaponized aflotoxin, botulinum toxin and anthrax. Jhadists point out that the result of Western freedom and women becoming equal are pictures of them torturing and humiliating male Iraqi prisoners as revealed in the Abu Grahib prison scandal. We can only shudder at the possibilities of having equal opportunity dictators and megalo-maniacs. The argument that women’s innate goodness prevents such a reality is offset by those who believe “Power corrupts!” Obviously, gaining equality for women isn’t as simple or perhaps as desirable as it sounds. Radical feminists, for instance, wondered why women would want to be like men. It seemed like lowered expectations to them. If anything, men needed to become more like women---compassionate, nurturing, peace-loving and non-violent. Oddly enough, that piece of the equality pie didn’t get eaten very much by the media, social reformers and, especially, by men. “Pussy-whipped” and “wimpy” men are not a popular item. The fear of emasculation has increasingly competed with our fears of war, terrorism and environmental disaster. Watch any television ad for household cleaners, and it is evident men are still mostly absent from smelly bathrooms and encrusted casserole dishes. This brings us to another point about gender equality. Men are typically physically stronger than women. Therefore, how can the genders attain truly attain equality unless females are “trained” to be as aggressive and strong as most men? Indeed, the vast majority of female domestic violence victims do not fight back physically. Those inclined toward aggression use weapons to even the playing field, but most women indicate that aggression is beneath them, that they don’t want to emulate the Amazons and prefer to get help for their partner or leave, if necessary. (This may not be the case if the woman suffers from severe mental illness or a personality disorder.) This perhaps is the most difficult area of gender equality that advocates must address. Many women want men to become less aggressive and violent, developing their nurturing and caring side instead. Until that happens, how can women live equally in an aggressive world? We also might ask how women can live equally in a passive-aggressive world. Just because women enter male bastions of power, doesn’t mean they will be welcome. As mentioned previously, the military is a glaring example. Another is the field of technology. Although young females are encouraged to take math and science and play video games, if they get high tech jobs, they may find themselves locked out of promotions, shunned socially and harassed. More women are opting out of such negative environments, but, of course, that doesn’t change things. It would appear that we are saying that only the entire dismantling of patriarchy will solve our gender problems. A truly egalitarian society ruled by both men and women, not a patriarchal or matriarchal system (which some radical and sentimental feminists long for) is needed. We have few societal models to copy, except some (soon to be extinct) or extinct hunter/gatherer societies. (Read Peggy Reeves-Sanday’s book,” Female Power and Male Dominance: On the Origins of Sexual Inequality” for details.) How does society go about dismantling patriarchy? What do men have to do? Let’s begin by exploring power sharing and power relinquishment. Men have had a difficult time doing this historically. Our white Founding Fathers certainly struggled with concepts of equality of women and blacks. Visitors to the new Liberty Bell Center in Philadelphia, for instance, walk directly over the spot where Washington housed his African slaves. Washington owned more than 124 slaves who were freed only after his death. Women initially had no voting rights. The intrepid few men who have joined the ranks of feminists have often been reviled by their gender and by those male-identified women, as previously mentioned. (Famous men who were for women’s rights include Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Henry Ford, Bertrand Russell, John Stuart Mill, Daniel Defoe and Frederick Douglass.) Although it would seem a simple concept, eqalitarianism has its detractors. Men who believe in equalitarianism, for instance, don’t buy it. Instead, their tenets are: (1) every person counts (2) every privilege carries an obligation (3) every person has the right to responsibility (4) every person has the right to be treated fairly (5) we should treat every person with some minimum of respect. 5 Were these fellows around when the Constitution was written? No, their philosophy is a reaction to their perception of feminism’s “unfairness” and “blame-game” tactics in attempting to gain equality. John Knight is not for gender equality. He is the founder of the father’s rights organization, The Father’s Manifesto. Its Reaffirmation and Declaration asserts: “We signatories to the Father’s Manifesto, responding to natural and Biblical laws, in defense of our nation and our families, hereby declare and assert our patriarchal role in society. America is an experiment in freedom and the feminist experiment in freedom, under the guise of ‘equality,’ unleashed a panoply of social ills which have become a cancer on our land, led to the moral and economic destruction of our nation, made American a house divided unto itself, created a vast underclass with a bleak and bankrupt future and is the greatest national disaster we have ever faced…” 6 On the other hand, the official position of the Swedish government on the status of women and men states:” A decisive and ultimately durable improvement in the status of women cannot be attained by special measures aimed at women alone: it is equally necessary to abolish the conditions which tend to assign certain privileges, obligations or rights to men.” Men face many challenges on the way to equality, equal parenting being only one. In the 1980’s, due to the women’s movement, men began to organize themselves around such issues as fathers’ rights and responsibilities, setting up fathers’ centers to offer counseling, parent education and support as well as developing an influential “father’s movement” responsible for child support, visitation and custody reform initiatives. The concerns of single fathers were also being addressed. Today the legal landscape of fathers is changing. Indeed, they more frequently get custody of their children, although many activists feel men have a long way to go in this matter. Equal parenthood also means that fatherhood has to be cherished by men as much as motherhood is to women. A good start would be a change in the toy department. Boys need to have dolls to nurture, not military figures to kill. They must see men as care-givers in the home and in the media. I would posit that if more men cherished fatherhood, they could not tolerate patriarchal abuses of power. Another area that needs to change is the government, but, un-like the Swedish government, our government has always adhered to the doctrine of gender inequality, and so its role in fostering men’s equality is dubious. For instance, women have been given benefits when they leave a job to follow their husbands when their jobs changed; the same hasn’t been true for men. In nineteenth century America, a man would be tried for his wife’s criminal acts and imprisoned if she were found guilty. 7 Government programs were set up to aid mothers of dependent children but not fathers in the same position. The National Institute of Health spends nearly four times as much on female-specific health research as on male-specific research. The U.S. Department of Justice has on Office on Violence Against Women, but none for men. Perhaps the most difficult equality challenge for men will be in the sexual arena. After all, sexual privilege, sexual entitlement, dominance and prowess have defined male sexuality for millennia. The power can be illusory as anyone with a fickle penis will tell you. Herb Goldberg writes in his book, The Hazards of Being Male, that the male’s relationship to his penis is ambivalent at best. “He has an adversarial relationship with his penis; he feels victimized by this capricious organ between his legs that seems to have a mind of its own. His feelings of failure, self-hatred, fear and inadequacy drive him to regain his performance competency as quickly as possible when a problem arises.”8 To share sexual power will mean feeling less concerned about performance and more about endurance of relationships. To share sexual power will mean relinquishing the myth “A stiff prick has no conscience.” This could just be one of the most destructive messages young men and women receive about male sexual entitlement. In essence, men are mindless creatures ruled by their hormones. (Remember men have rationalized women’s hormonal disruptions as reasons for disenfranchisement.) In such a circumstance, it is up to the female to maintain moral order. This is a tall order when women are often overpowered by male strength and determination. Such a message discourages men’s abilities to use judgment and sensitivity in sexual relationships. If men take gender equality seriously, they will demand that all men’s public restrooms have diaper-changing tables. Men will have the choice of hyphenated names when they marry. The military draft will no longer be exclusive to men. Heterosexual men will be able to kiss and dance together (in all countries) and wear dresses, if they wish, without social backlash. More men will take the kids to doctor appointments and school meetings, cook inside (not just grill outside), learn conflict resolution skills by third grade and will not tolerate abuse of the powerless wherever they may be. There will be as much air play for groups like Fathers Against Drunk Driving, Men Can Stop Rape, the National Coalition of Free Men and DADA (Dads and Daughters) as there is for the NFL and the NRA. The list is endless, but it just might be the recipe for the dismantling of patriarchy. FOOTNOTES

Jordana Hall has an M.A. in English from Texas A&M U-Commerce, and teaches English at Wiley College in Marshall, Tx. She will complete a Ph.D. in English Studies with an emphasis in children’s literature and literature theory from Illinois State University in December 2019. She shares a deep love a fiction with fiction with her husband and six children. Sickness Blows rain down on my face and arms as I wrap them tightly around my head. His shouts are loud, but the ringing, I know, comes from my ears as he slaps my head again and again. I stagger, and cry, and beg. I can hear Arturo yelling, but it is already far away as I stumble and fall into the deep pit that we had been digging together--a hole that we had imagined would become a secret, underground lair (fun and games). I don’t even know what made him angry.

“Stop! Stop, man!” Rocks and dirt begin to rain down on me as Jordan struggles free from his friend’s grip on his arm and grabs whatever he can find from the pile of rubble by the pit to throw at me. He kicks and screams and pelts me with rocks in his madness while I watch Arturo rushing away to find a grown up. It feels like forever before I hear the deep shouts of Arturo’s father as he and his son race towards the one-sided fight. Through the space between my skinny arms I see Mr. Florez pull my brother, Danny, away, wrapping his tense body up in strong arms as he struggles against the man. I uncurl enough to look at my brother more closely, but Danny’s eyes have reached that point; I know it is not really my brother that beat me bloody. His eyes are blank and there is an edge of . . . something. It doesn’t belong on the face of a thirteen-year-old, I know, though I have seen my brother wear that same face off and on for as many years as I can remember. It is all the more terrifying for the contrast that I know I will see once he can think clearly again. Since that frightening day long ago, I have learned that my brother’s behavior is not as unusual as I once thought, though his episodes can be very extreme. He was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder in his thirties when he finally sought help after having struck his daughter. He wasn’t even aware of who she was at the time. The National Alliance of Mental Illness describes the disease as a “chronic mental health condition characterized primarily by symptoms of schizophrenia, such as hallucinations or delusions, and symptoms of a mood disorder, such as mania and depression”. Raised in a period where mental illness was still stigmatized to an extreme degree, any symptoms that my brother displayed were either ignored or covered up as much as possible for fear that he would be locked away. “But he’s so sweet with her. It can’t be true. He’s the most, gentle man I’ve ever seen, and he absolutely dotes on his little girl!” It was a common refrain from family acquaintances after the crisis that led to his diagnosis, but I had born witness to many moments where my loving, doting brother could turn violent and seemingly insane for the slightest offense. I knew that he could and would turn on his daughter in the same way--through no fault of his own. Once, we had both promised to babysit our young nephew, and I then refused to get out of bed. Danny grew angry, and then furious, before holding a pillow over my head. I remember struggling for what seemed the longest minutes of my life against the pressure that held my face against the mattress, the soft yet suffocating feel as he pressed just a little bit harder, then harder yet, as my arms thrashed and reached backwards scrabbling to beat futilely against him. “I’m so sorry,” he cried, pulling at his hair as I gasped for breath when he finally let me up, having realized what we was doing. He was like that—turning on a dime. One minute he was kind and sweet, letting me snuggle against him in the dark because he knew that I was afraid. The next he was cruel, lashing out for things that I would roll my eyes at if I wasn’t too busy being terrified. “I did that,” he would ask, looking at my bruises in shock and horror. Danny was never cruel, but he did frequently lose himself in delusions and mood swings. His illness made my childhood a nightmare at times, but I can only imagine the pain and guilt he must have felt after one of his bouts of violence, seeing the people that he cared for more than anything in the world shy away from him, often bruised and bleeding. His own fear must have been nearly as overwhelming, but like our mother and the rest of our friends and neighbors, he never mentioned his “peculiarity.” It just wasn’t done. “You know, I’m afraid of the dark too,” he said to me once, after. “But the dark is inside of me.” His shoulders were tense, and I knew that he was thinking of the way things were when we were children, afraid of that same darkness hanging over the head of his little girl. “Then let’s turn on the light,” I said, clutching his hand tightly. Though mental illness is still stigmatized and misunderstood today, it is far more acceptable to seek out treatment for behavioral issues. My niece is a happy little girl with no memory of the incident that forced her father to finally seek to understand the darkness that cast a pall over our childhood. Now he regularly takes medicine to help combat his mood swings and delusions and makes regular visits to a therapist. How different might our lives had been if the world was ready to admit that there is nothing wrong with needing a little help? References “Schizoaffective Disorder.” National Alliance of Mental Illness. Nami.com www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/Schizoaffective-Disorder. Accessed on 1 Oct 2018. Lois Greene Stone, writer and poet, has been syndicated worldwide. Poetry and personal essays have been included in hard & softcover book anthologies. Collections of her personal items/ photos/ memorabilia are in major museums including twelve different divisions of The Smithsonian. The Smithsonian selected her photo to represent all teens from a specific decade. DAD“How can you still love your father?” At first, I wanted to respond with something clever after hearing the totally stupid sentence coming from another woman. Why is time a factor in how long love continues? But I chose to not answer.

My mother took my childhood bruises and treated them so infection might not set in; my father kissed away the pain. My mother washed my thin blonde hair and combed out the snarls; my father told me how it glistened golden in the sun. My mother hand-sewed pretty dresses she also designed; my father captured moments with a camera that was always ready to take a fleeting instant and make it permanent. When I was ill, they took turns staying all night at my bedside; I was too young to wonder how my dad managed to go to work the next day or my mother got my sisters ready for school. Early adolescence, I hand knit a pair of bold-color plaid socks for my dad. His work suits were beautifully tailored, his socks held in place with garters, and trousers held up with suspenders, as was the fashion then. His felt hat with wide grosgrain ribbon complimented his outfit. Weekend clothes had him in a plaid felt hat, and slacks with a belt. I assumed he’d wear my shocking socks then. Instead, he put them on, smiled and his dimples winked, looked at me with his powder blue eyes, and nodded his head. He went to work in them, and probably allowed others on the Long Island Railroad to notice what his daughter had knit with her own hands. In taxis, returning home from Broadway musical shows, there were two ‘jump-seats’ that pulled down and passengers using those rode backwards. He didn’t like riding backwards but he and my mom took those seats so their three daughters could ride on the cushioned regular bench-seat. I never said ‘thank you’ as my comfort was always considered, and, as a child, didn’t the world revolve around me? We explored the farmland of Long Island, the quiet streams in the Pocono Mountains, sat outdoors on a summer night listening to opera at Randall’s Island, planted Victory Gardens in our backyard, stood around the piano each night singing as my mother played, danced in the living room to the individual recordings where the turntable was concealed inside a pretty cabinet, and marveled at the tiny new wonder of television in the late 1940's. He put a ballet barre in the basement when I took that dance class, erected a real theatre curtain down there when I began to write and perform skits for the family, presented me with a wooden case of oil paints and sable brushes when I wanted to paint, gave me a funny note and money to spend on my dream figure ice skates, and gave me a different independence with my balloon tired/ no speed bicycle. My mother listened, lectured, advised me when age twelve was becoming thirteen; she was never too tired or busy for me. My father read philosophy to me, brought my mother flowers, constantly told her how much he loved and valued her, showed us that our family was a gift given to him. He had character and personality that I eventually wanted in a mate and the kind of father I wanted one-day for my own children. He felt one’s speaking voice should be free from any specific inflections and bought a fat-reeled tape recorder. When I was preparing a speech in early high school, I spoke into the machine and could clearly hear that I needed to drop my pitch as a microphone seemed to make it higher. He also used that recorder when he was taking 16mm home movies so we’d have some sound of what he was filming; he told us one day there’d be a device to capture both sound and movement for home use. He took me to summer camp in the Berkshire Mountains when, one season, I started after the session had begun. I never even thought about his long ride back, with his left arm getting sunburned from having it against the open window. He drove me to another state and even unloaded all my possessions when I left for college; I never thought that he might not have been fit enough to climb the 5 flights of stairs constantly in the no-elevator building; I lived on the 4th floor but all the trunks had to be brought to the basement and unloaded by hand there. He went up and down, and I simply put items away at the same time. I was 17 and life was an adventure with loving parents just continuing to do what they’d always done making me feel important and safe and happy. How can I still love my father who has been dead all of my adult life? Why would that loving expire just because life ceased for him? As a grown-up, I realize that he missed living, seeing his children grow, aging with my mother who never even looked at another man for the rest of her life, sharing in the wonders of technology, holding grandchildren in his arms, exposing his family to the wonders he felt constantly surrounded us. I’ve learned, with age, that I am not the center of the universe but so appreciated that, for a period of time, I was. I miss him still. When a magnolia tree blooms, I remember the one he and my mother planted in 1941 when it was a twig, and the pleasure he had watching it get larger. When I see works of philosophers, I remember his appreciation for words. If a scent of lavender passes my nose, I recall his after-shave aroma, just as I can still see the mug of foam and sable brush used to lather the shaving cream on his face. I like myself, value my family, appreciate my intelligence, enjoy my abilities at sports or art or writing or music, for examples, and these came about because of my parents. Why would time stop feelings? ©2006 The Jewish Press  Jordana Hall has an M.A. in English from Texas A&M U-Commerce, and teaches English at Wiley College in Marshall, Tx. She will complete a Ph.D. in English Studies with an emphasis in children’s literature and literature theory from Illinois State University in December 2019. She shares a deep love a fiction with fiction with her husband and six children. Empty Spaces I was 39-years-old when my appendix ruptured while I was pregnant. Phineas was born in our home after only 5 and ½ months while I was recovering from emergency surgery. He was 13” long and weighed only 1.4 pounds. He fit in the palm of my hand. He lived for one hour; he changed our lives forever. This is his story.

Though he is tiny enough to be held safely in a single hand, I cradle the little body by cupping my hands together. His chest rises once and a thin arm lifts just slightly—it falls. His chest rises again . . . and again . . . and again. I count every rise and every fall. They are precious. Just outside the door there is shouting, and footsteps rush up and down the hall. I hear everything through the thin walls, but the only thing that exists in that moment is in my hands. He breathes slowly, laboriously. Even if he could open his eyes, they would not look like the eyes of his brother, his sister, or even any other child. He is too new. He is too early. But he already holds a place of equal size in my heart, and it is bursting with fear and hope that war against each other in that moment. “Stay. Stay! Hail Mary, full of grace. The Lord is with thee.” I pray like I have never prayed for before. In this moment I pray to God, but I also pray and ask Mary to speak on behalf of my son. She is a mother. She understands. I mutter the familiar prayer, and I rock back and forth, not for him, but for me. There is no comfort. “They’re here!” My husband’s shout is frantic. I hear more shuffling and knocking against walls. Grunts and worried shouting and fighting as brothers and sister fight for position to see and know, but Mark pushes them back. “Don’t look,” he says urgently, turning them away. “Don’t look,” and his voice breaks just as the paramedic bursts through the door. I have not stopped praying, rocking, or staring at the thin chest that still determinedly rises and falls. Such a simple thing, breathing, but every breath fills me with pride and I smile through tears. “Oh, he’s not gonna make it. Too small,” the paramedic says, pulling up short as if all of the urgency has drained away. “Shut up,” a second paramedic snarls, shoving past his partner and kneeling beside me as I sob and shake my head. I can’t stop praying. “It’s ok,” he whispers. “We’re going to have to cut the cord now.” He looks at me, and I know what he’s really saying. They will cut the cord that holds my tiny son to me even now while I hold him in my hands. My whole body rebels. I tremble and sweat. All I think and feel in that moment is NO! The look in his eye as the paramedic stares back at me says “Yes. You already knew this.” The moment ends, but I am numb now. Somewhere inside me I know that they have cut the cord. One paramedic has taken my son. He’s taken my son! Now I’m screaming and kicking. Trying to reach him again as the man carries him away. My husband is sobbing and reaching first for me, then our son, then turning and blocking the door again. It’s clear that he needs to do too many things at once. Is he husband? Is he father? Can he be Phineas’s father right now? Is that allowed? Are we allowed to think of the little boy who is still alive, but also clearly already gone? Can this be his moment, because I really want this to be Phineas’s moment. I know what my husband would choose, but I also know that Mark is unsure if that is a right choice. I can just see five young faces looking on in what must be terror—a look I’ve never seen on their faces before. I stop screaming abruptly and still. The paramedic is moving me towards the door. I can walk though I still cry and shake. The rest is like a dream. “It’s okay. We’re all going to be okay,” I say as I pass the sea of young faces that should look away, but can’t. And I’m just too tired and sad to make them. “Do what Daddy says. It will be okay.” I have just enough time to see my second eldest son’s face. He looks haunted. His eyes are red as if he needs to cry, but his face is dry. Later he will cry, wracked with sobs, shoulders shaking as he begs for me to understand. “I was happy! I was happy because they said that you would be fine! I’m so . . . I’m so sorry!” The rest is a dream, or a nightmare. I’m taken to the hospital in an ambulance. Phineas is taken to the hospital in a separate ambulance, and they would later explain that he passed away before they even arrived. He lived for barely an hour, and during more than half that time he lay carefully cradled in my hands as I prayed for the soul that left us behind. After some basic care I’m taken to the maternity ward. I lay in a bed identical to those where I gave birth to five other, healthy children. I listen while families in nearby room celebrate and laugh. Their tears are of joy. Later my husband shuffles into my hospital room, his face lined with exhaustion and sadness and holds my hand. A nurse comes to check on me and is sympathetic. She asks if we have other children. “Yes,” Mark says, monotone. “Five.” “Oh. Then you’ll be alright,” she says simply. I stare at her and hate her. Two years later. Eight spaces fill the dinner table including our youngest daughter, Imodgen, but everyone is always mindful of the empty space |

Categories

All

This website uses marketing and tracking technologies. Opting out of this will opt you out of all cookies, except for those needed to run the website. Note that some products may not work as well without tracking cookies. Opt Out of Cookies |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed