We are moving towards that path. I cried as I watched the Nigerian soldiers shoot at peaceful protesters in Lekki, Lagos, Nigeria. It was a gory scene and I was scared of the chaos it will create in the country. The shooting was a reminder of the Asaba and Calabar genocide that happened during the civil war. It was an indication of the political instability and insecurity in Nigeria.

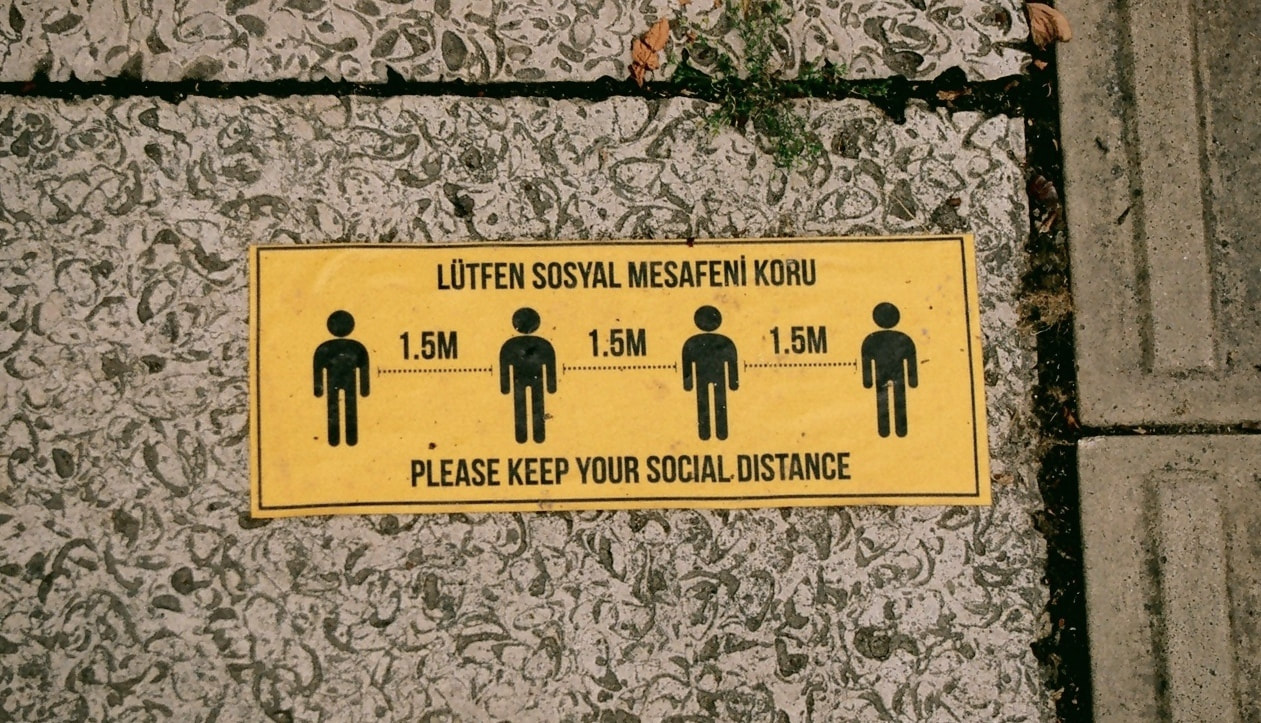

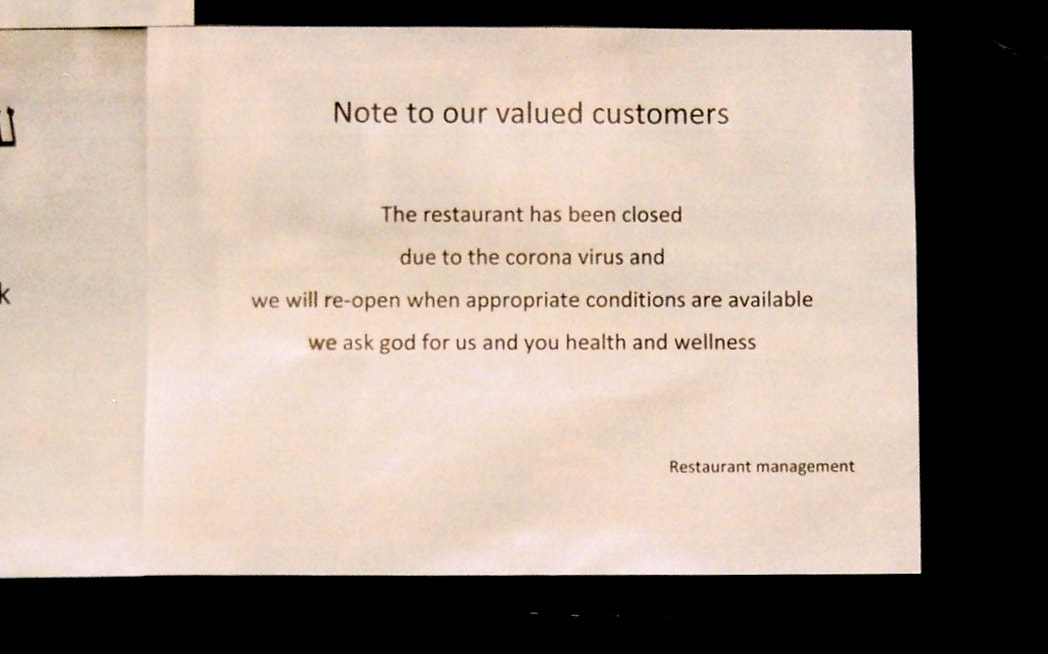

Police brutality across the country provoked a nationwide protest; it was an opportunity for the Nigerian Youths to express their feelings against the poor treatment of the Anti-Robbery unit towards them. The EndSars protest was a crusade against the rough treatment of the Anti Robbery unit of the Nigerian Police Force towards the youths. Youths were victims of the killings, illegal extortion and harassment devised by the police officers of this unit; it is the prejudice of the officers that led to a nationwide campaign against their unlawful acts towards citizens. Organizers of this protest demanded for the dissolution of the unit from the Nigeria Police Force. This petition came along with 5 demands which include the immediate release of arrested protesters, justice for the deceased victim of police brutality along with an appropriate compensation for their families, the setting up of an independent body to oversee the investigation and prosecution of reports of Police misconduct, a psychological evaluation of disbanded officers and increase in police salary so they are compensated for protecting the life and property of citizens. It was a demand that required an urgent attention. It began on October 8, 2020. Prior to this day awareness was raised on different social media platform, denouncing police brutality in Nigeria. The event that sparked the protest was the unlawful killing of a Youth by the Police Officers of Anti-Robbery Unit in Ughelli, Delta State. The trend of killing innocent youths, arresting youths in disguise of being an online fraudsters has being an activity of the Anti-Robbery Unit that is overlooked by the Nigeria Police Force. The EndSars protest became a revelation in 2020 despite its establishment in 2017. Police brutality has raised the question of trust over a public agent that should protect the lives and properties of people across the society. EndSars started as a Twitter campaign in 2017 using the tag #End SARS to demand for the dissolution of the Anti Robbery Unit by government. The continuity of unlawful killings of youths, extortion and unlawful arrest of youths led to an aggravated yet peaceful approach to the protest across the country. It was a time that created an opportunity for people to speak against the unlawful arrest and inhumane attitude of the officers in the Anti-Robbery Unit of the Nigerian Police Force. Few days later, the Inspector General of Police, Mr Mohammed Adamu announced that the Special Anti-Robbery Squad has been disbanded at the same time members of the unit have been withdrawn from the unit. The context of this announcement was followed by an unpleasant gesture and body language by the inspector. The story took a different twist when the Inspector general of police declared that the Special Anti Robbery Squad was changed to Special Weapon and Tactics. The idea was seen as an act of recycling within the unit, recruiting the officers of the disbanded Special Anti Robbery Squad of the Nigerian Police Force. The decision of the Inspector General of Police led to a rise from police reform to bad governance across the country. A petition to stop police brutality became a central discourse towards pertinent issues neglected by the Federal Government of Nigeria. A peaceful movement also an organized protest yet the President failed to speak to Nigerians over the issues raised by the protesters. The Nigerian Youths filled the hole left by prominent activist such as Gani Fawehinmi and Fela Anikulapo Kuti. The Soro Soke generation did not hide their feelings; a raw expression of speaking to power took another dimension in Nigeria. Hope was regenerated yet there were other parties that were employed to manipulate the plan for a better Nigeria; it was action awaiting execution yet we are not aware that it will come very soon. Citizens supported the youths; they were not excluded from the struggles yet the Leaders fail to acknowledge the importance of what we asking for as Nigerians. A peaceful protest became an affair of hoodlums across the country. It began in Oshogbo when the convoy of the Governor was attacked by thugs along the state capital. The emergence of hoodlums raised a question, where is this coming from? It was not what the protesters had in mind yet we had no clue that the other party had their plans. We are not aware that an attacked is being plotted by the other party to stop a peaceful demonstration align towards building a better Nigeria. A protest against police brutality became a political and social awareness in Nigeria. The protest captured a global attention yet the other party chooses to silence those who voted for them because what they are asking for is not what they can do. The other party was against the demonstration because of what they will lose if the protesters emerge victorious in their fight for a better Nigeria. Hoodlums became the only option the other party can implore to disrupt a widely recognized protest. The destruction and demolition of facilities by hoodlum was a strategy that failed the other party; the youth were resilient and courageous yet men of the other party kept looting and destroying public properties as a strategy for disguise, tracing the incidence to the EndSars protest yet it failed because they did not get the support of the citizens. The Jail break in Benin and destruction of police stations and barracks led to a nationwide curfew yet a day came in Lekki; a day when the other party struck at Lekki. Despite raising their flag as a sign of patriotism, the other party called for the men in green to disband protesters using guns and bullets. October 20 was a gory day in the history of Nigeria yet it was the day we knew the beast the other party had unveiled. A curfew was imposed on this day by men of the other party; there were reports that the inspector general of police had called the anti-riot squad to disband the protester at Lekki Toll gate. At dawn the men we thought were police officer were actually the military officers interfering on what I interpret as an internal issue. Many lost their lives but the other party told its followers that there was no casualty. Few days later, it was revealed that many lives were lost after a live video of killings was shared on different social media platforms. The other party told its people that it was a fake yet the international community had a proof that there was a massacre on this day. As a citizen I was disappointed with the men of the other party for lying to its people while the truth was obvious. It was an exposition of insincerity of our leaders towards its people. The EndSars protest was a revelation to the citizens of Nigeria. It was an exposition into the monster we have embraced and supported for 21 years of our transition from military to the Federal System of Government. We have seen that men from the other party are not capable yet they want to rule over our affairs. Secret affairs were exposed, the body language of our leaders prove that they are selfish and unwilling to restructure Nigeria. A country of 36 states and 774 local governments cannot continue to languish in economic and social deprivation. The protest was an awareness of the poor governance across the country yet men of the other party were not ashamed to admit to their failure neither are they ready to correct the mistakes and error. Nigeria is moving towards the right direction as a state but the question of upholding the lessons remain a puzzle until 2023. The fight for better governance and end to police brutality will continue; people should be educated on governance and their expectation towards them to build a better Nigeria. I believe Nigerians are enlightened yet I ask, can we sustain the knowledge for 2023? We need new faces, a different system, new ideas and innovations. Police brutality is the subject of discussion; it is an issue that has led to abuse of our rights and expression as citizens of Nigeria. We have lost many souls to the detriment this act has brought upon us, we have buried more people on the basis of physical harassment by the enforcement agent that should protect the lives and properties of the citizens. Police Brutality has become a question we are yet to answer, a clue that Federal Government have chosen not to solve despite the press to stop Police brutality across the country. Authorities opt to threaten its citizens; it opts to arrest the protesters, freeze their account and oppress those who oppose them. Eromosele illegal detention and the unfair treatment created by the Federal government are proofs of a regime that is neither concerned about the life and properties of its citizen. The end against police brutality was beyond police brutality; it was a fight against a government who chose the Police as tool of oppression against the citizen. The struggle continues, Nigerians have chosen not to back down despite the effort of the government to turn its ears from the voice of its citizens.

0 Comments

Lois Greene Stone, writer and poet, has been syndicated worldwide. Poetry and personal essays have been included in hard & softcover book anthologies. Collections of her personal items/ photos/ memorabilia are in major museums including twelve different divisions of The Smithsonian. The Smithsonian selected her photo to represent all teens from a specific decade. Pasted-on expressions“Welcome” was written on a cardboard poster greeting me, and other wives, who had accompanied their husbands to the convention. It was the second thing I spotted at the hotel’s mezzanine level; the first was a smile. As if stamped by machine, the many faces were almost identically upturned. I approached a table covered with a color green felt-cloth. Copies of auxiliary activities were neatly arranged. My name and hometown were transferred into print on a plastic covered tag, then pinned to my blouse. “Welcome” was inked above my name. Coffee was available; conversation was a by-product. The day’s events offered a makeup lesson at 10am, followed by handwriting analysis. According to the program, a ‘delightful’ luncheon of chicken salad, then a fashion show, would complete the morning’s activities. I flipped the page to tomorrow’s schedule. Late registration and coffee preceded the bus trip to a local university. Points of interest along the way would be indicated. A flower-arranging demonstration should highlight the trip. Freedom to shop was the afternoon fare. On day three, a diet and exercise expert would complement the coffee hour. Dancing class and/or palm reading should provide an interesting morning. I left the mezzanine with leaflets, maps, and three-day schedule to find my husband. Perhaps I could attend meetings with him. Under the guise of entertaining and enriching, the women’s agenda was designed to keep them busy and out of the way. My husband’s gentle “no” made me wonder if a woman was a threat to the male meetings or to the other wives. Were all females united under cosmetic demonstrations to protect those who were not capable of cerebral activity? Or might Joe feel inadequate because his wife’s subculture is shopping while Sam’s wife sits beside him in a class making notes and understanding the discussions? Dinner and bingo, dinner and an art auction, dinner and a banquet will really make the convention a memorable event. Auxiliary activities are acceptable to many. However, the assumption that all would be enthusiastic upset me. After five years and two summers of university life, it was comical for me to be ‘treated’ to a field trip to a university for a dainty salad, home-ec, and “see this big school run”. Handwriting, palmistry, and makeup insulted me. If I hadn’t learned how much or how well to apply the latter at this stage in life, or believed the former, I’d feel rather pathetic. Now that I finally can stroke lipstick minus a mirror, should I spend valuable time teaching myself to brush my lips with pure sable? Handwriting analysis was fun at age twelve; I wasn’t pre-teen anymore. Why couldn’t some of the women meet and exchange ideas on day-care-center problems, equal rights/pay, working wives, single-parent homes, emotional health, contraceptives, state alimony laws, mastectomy attitudes. Coming from different places, women could explore how one another’s communities deal with similar situations. Perhaps they could hear a psychiatrist discuss uprooting and the whither-thout-goest syndrome. Has mass media, or perhaps their own mothers, reassured women it’s okay to dislike their children at times, be angry when mate’s job moves them from familiarity, feel smothered by daily demands, for example? Might women examine situations with aged parents and guilt for not wanting to care for them? Can’t convention females at least have the option to unite and exchange fears, needs, social structures! My thoughts were interrupted by a passing fashion model. In a bra-less halter tennis dress, tinted eyewear, flowing hair, bangle bracelets, and rope pearls worn as a choker in front and hanging behind, she looked terrific for the terrace. Would you believe she was attempting to convince the audience that the garb is actually for playing! “Welcome.” It said that right on my badge. Welcome women.... next year’s exciting plans include the art of pedicure, a bus trip to a real decorator’s studio, satin pillows vs. sleep bonnets, how to look as if you’ve done nothing all day, where to apply perfume? This actually happened in 1980, and I wrote the above for “Graduate Woman”. At the next conference we attended, I merely walked in with my husband as it were a business meeting. There were no badges necessary; I was the only woman in the room. The wives were bussed to a local shopping mall for hours of that activity. While the discussion was of little interest, group shopping and prodding to spend ‘more’ was just not me at all. Several years passed. At a convention in Miami, and women were now in the profession with some wearing badges to attend lectures, I walked in with my husband and pretended my tag had been left in the room. During question time, I raised my hand, and with knowledge learned from reading journals and working for my husband occasionally, I mentioned a specific study not brought up by the speaker and what were his thoughts about such. Congratulated for ‘good question’, I did have to exit rapidly once the session was adjourned else be found out that I didn’t belong. We’re starting a calendar that says 2021. Yes, there are still women who prefer a spa day to hours at lectures; unlike my experience decades ago, now there’s a choice! word-association ‘Do not pass Go’ ... a Monopoly board warning or command? I never did take a pass/fail course, but I did pass the baton in relay-racing, got a hall pass to leave class during high school, heard an old song that said ‘pass the ammunition’.

And code? In religious school, I learned about the Code of Hammurabi, some really important laws to deal with civil and criminal things. The combination lock on the steel rectangle in the Girls’ Gym, high school, had turn right/turn left/three numbers but I didn’t think of that as a ‘code’. Homeroom closet held my outer coat, and that locker was to hold mandatory gym suit or my clothing when I put on the one-piece, balloon shorts, puff sleeve attire washed and starched by my mother. A code was talking Pig Latin when I was pre-teen, holding the heavy black Stromberg Carlson telephone that was tethered to the wall; I was sure my parents had no idea what ooh-yea meant. Word count. My gosh, that took so long adding-up every single one I carefully wrote with my fountain pen’s color South Seas blue. Why didn’t the teacher accept page-count instead! When I learned to type, instructors also wanted word-count and I couldn’t just total lines as some words were short and others long! Tedious. And I always-always loved words. My new ipad, during our current Pandemic, was ordered sight-unseen and mailed to me. The computer store, although actually open in a local Mall, was not going to transfer data from my previous one even if I’d gone in person, donned in a mask covered with a face shield for extra protection. By phone, a grandson 400 miles away, ‘walked’ me through the transfer and erasing the previous device to mail to the company’s trade-in place for some cash-back. Then came the e-mail: while my former tablet was ‘clean’ and such, some encoded item still present had to be removed. Go to Find My Phone; my phone was next to me so why should I ‘find’ it. I looked in ‘settings’; I never had that turned on, so what was I to do so the company can finish evaluating my trade-in? Ah. Call my Guru grandson back; he got my private information and took over my tech item here and dealt with the company. Well, suggesting I change my password, and to something I might even remember, my husband and I sat at the kitchen table. A real table, by the way, and not a counter with high stools that, at our ages, we’d have trouble even climbing on. He said ‘make it strong’; why isn’t a weak one as good as everyone will expect strong? I can remember weaker ones since those don’t need upper case, lower case, numbers, math symbols, and be at least eight letters long! Okay, how about a ‘p’ and maybe a ‘t’ to start? The ‘p’ might look both upper and lower case, so that was out, the ‘t’ when handwritten might look like a plus-sign. Out. An ‘s’, ‘c’, ‘k’, ‘m’, ‘n’.... oh you get the idea, also might confuse me since I’d be handwriting those in my little ledger of such. A lower-case ‘l’ seems too much like the numerical ‘1' so that was out. Let’s go back to the letters, I suggested, and also do the math symbols. Writing out a dollar sign appears that I’m crossing out a big ‘S’, and the tic-tac-toe board had me want to play as its meaning as hashtag just isn’t in my memory bank. The ‘&’ looked like a musical symbol; oh let’s do symbols as the last step in creating a password! Okay, how hard can numbers be? We got four numbers. Could I remember those easily? Possibly if the other necessary things for a password were also meaningful. And I shouldn’t use birthdays, anniversaries, graduations, old phone numbers.... why! Who are all these people in space that know these about me! All right. I won’t use any of those. Creating a password is complicated. On some medical portal, I could use the name I gave my childhood canary and that’s okay, but it isn’t strong-enough for my tablet and phone. Seems medical records are more private than emailing ‘hi, how’re you doing during this global crisis, and how’s your family holding up’. Password finally done and took longer than it should. But I have to enter it in the device, twice. Done. Oh, I have to do that again on my phone? Okay. Uh-oh, I’m not finished with this easy process: two-factor authentification. What’s my passcode? Geez. Passcode is not password; how do I open my devices using numbers rather than one digit that has wavy lines unique to me? Go to my ledger and look that up: there, hand-penned with a ballpoint (my fountain pen’s purpose vanished with smudgeless ballpoints). Oh setting up a tech thing is so easy. And changing passwords not a problem at all. And, of course, one does remember a passcode when the eyeball or face-recognition or digit doesn’t open the phone. When Pandemic ends, the public will hear how important a Geek is to do these things, for the small price of $100 set-up. I once thought moving pieces around a Monopoly board was confusing with the railroads, and which properties were worth saving and which ought to be traded if any player even would trade. Do not PASS Go... Maybe that would make a valid password..... nope, doesn’t have numbers or symbols.

TRUE STORY Ten years ago, I suited myself up in snug-fitting, job-interview attire. My toes screamed for mercy as I crammed them into the stiff leather pumps I saved for dress-up occasions. The hostaged flesh around my midline rebelled with equivalent fervor.

Desert Valley Regional Co-op (DVR) had solicited me as a potential candidate to fill a teacher vacancy in the vision department. I had limited experience in the teaching field. Several years prior to the interview, I worked as a substitute teacher. That taught me nothing other than I had no talent for interpreting, let alone carrying out the vague plans the teachers-in absentia left for me. My ambitious goal to ward off starvation and the bill collector compelled me to accept any and all positions the sub finder threw my way. Like a dog chasing after a rubber bone, I ran after every job offered to me. I never quite sank my teeth into teaching as a career, though. Like that rubber bone, it lacked a meaty satisfaction. I wanted to land a career with a little more flavor, not to mention with a more reliable income. After several years of subbing, a one-on-one aide position in a special needs classroom crossed my path. I applied. I looked good enough on paper to earn an interview. Before grilling me with questions, Mrs. Archer, the special needs teacher, shared what little she knew about the new enrollee. "He requires full-time support. That's where you come in. Among other things, the student—a nine-year-old—is multiply disabled: orthopedically impaired, non-verbal, and visually impaired." That little preview blind-sided me. I knew nothing about this population. At the same time, I knew not to let on that I was clueless. I wanted a steady paycheck. The health benefits provided an extra perk. Either no one else applied for the position or I wowed them with my impressive credentials and articulate responses—the district hired me. I had two months, the summer break, to mentally prepare myself to work one-on-one with this child. During that time, I researched resources available to the blind or visually impaired. I learned that the local library had a collection of braille children's books. A call to the Foundation for Blind Children (FBC) revealed even more. The University of Arizona offered an $8000 stipend for anyone enrolled in their program to train as a Teacher of the Visually Impaired (TVI). This news struck a nerve. Still in debt for a master's degree in physical anthropology that I never used—motherhood derailed my original Jane Goodall wanna-be plans—this revelation got me thinking. I survived substitute teaching. That meant I could do anything. Right? I secured an application, aced an over-the-phone telephone interview with the department head and mired myself in a new job and academia. The summer got hotter as I fretted over whether I'd jumped in over my head. * * * The first day of my new job rolled around, and so did my charge in his custom-fitted wheelchair. His handsome face and big grin belied his medically fragile condition. A premature birth at 24 weeks sentenced Armando to a lifelong struggle with cerebral palsy. Armando's mom accompanied him into the classroom. She introduced herself and her son to me. Next, she gave me a cursory rundown of how to operate the wheelchair, how to prepare and serve Armando's pureed diet and how to put on his orthotic device or AFO, a brace worn on the lower leg shank. After handing over diapers, wipes, and baby powder, she took off. Stunned by the reality of my new responsibility, I pulled up a chair and made nervous chatter with Armando. Judging by Armando's distressed countenance, the two of us had something in common—a comfort level that just about zeroed out. Over time Armando and I learned to communicate with one another. As an aide, I followed through with goals established by the physical, speech and occupational therapists and vision teacher. Like any other kid, Armando often balked at the "homework" they provided. Armando learned to communicate by tapping a bright yellow switch. I recorded daily news reports into this device. Whenever the nurse came in to give Armando water through a special tube that fed directly into his stomach, Armando shared the highlights of his day. Eventually, he learned to pause between statements so that the nurse had a turn to respond. Through this activity, Armando acquired the give and take of two-way conversation. Armando had access to another wheelchair-mounted communication device. He had an aversion to this equipment. It operated either with switches or in a computer-like touch screen mode. Now and then—maybe six times over the course of the school year—Armando tapped out a brief message. He let everyone know one morning that his wheelchair had a tune-up. On another occasion, he announced he had met a local sports celebrity. One morning Armando cried non-stop. No one had any luck uncovering his distress. That's when I took it upon myself to interrogate him on his little-used computer. Although at first reluctant, Armando tentatively reacted to my quest about what hurt, "Your head?" I asked, tapping the voice-activated picture of a throbbing head. "No," he tapped. I moved on to the next picture in the sequence, "Arms?" "No," he tapped again, but this time he kept tapping until he got to foot. "Foot," he announced. I rolled up his pants leg, ripped the Velcro fasteners on his AFO, and peeled off the brace. Next I took off his sock. An angry blister raged beneath. Mystery solved. Armando taught me a few things that surmounted what I picked up in my intense training as a Teacher of the Visually Impaired. Despite his condition, I learned that Armando was a regular kid. Although incapacitated, he had opinions and a strong personality. The most important message conveyed to me though was the value of patience and waiting. Students with limited communication skills at their disposal often slide into a passive mode. Their caretakers, like well-intentioned genies, answer every one of the child's anticipated, unstated wishes and desires. Armando had little use for his expensive communication equipment. The adults around him took care of everything. Armando's desperation to have his painful foot condition addressed compelled both of us to slow down and methodically consider our options. Thanks to Armando, I learned to step back, watch and listen. Now, I liken myself to the school bus that stops at all railroad crossings. Sure, it seems senseless. There's no sight or sound of an oncoming train. But on that rare chance that I miscalled that assessment, I've at least made all efforts to do the job right. * * * My earlier experiences as a substitute teacher still haunt me. They resurfaced during my job interview at DVR. I still had doubts about whether I had it in me to teach. Just in the nick of time, my successes with Armando skidded into my head. They emulsified my uneasiness and gave me the confidence to endure the stressful Co-op interview. I must have said something right. DVR invited me to join their ranks. Over the past ten years the lesson learned from my original mentor, Armando, served me well. Stop. Look and listen.

A Timid Romance With Science Fiction: |

| Eric D. Goodman is author of Setting the Family Free (Apprentice House Press, 2019), Womb: a novel in utero (Merge Publishing, 2017), Tracks: A Novel in Stories (Atticus, 2011), and Flightless Goose (Writer's Lair, 2008) as well as the forthcoming adventure thriller, The Color of Jadeite. A past literary contributor to Baltimore’s NPR station, WYPR, Eric is curator of Baltimore’s popular Lit & Art Reading Series and a regular reader at book festivals, book stores, and events. Eric lives and writes in Baltimore, Maryland. Learn more about Eric and his writing at www.EricDGoodman.com. |

| Although Sally Whitney has spent most of her adult life in other parts of the United States, her imagination lives in the South, the homeland of her childhood. Both of her novels, When Enemies Offend Thee (Pen-L Publishing 2020) and Surface and Shadow (Pen-L Publishing 2016) take place in the fictional town of Tanner, N.C. The short stories she writes have been published in literary magazines and anthologies, including Best Short Stories from The Saturday Evening Post Great American Fiction Contest 2017 and Grow Old Along With Me—The Best Is Yet To Be, the audio version of which was a Grammy Award finalist in the Spoken Word or Nonmusical Album category. She currently lives in Pennsylvania and can be reached at www.sallywhitney.com, www.facebook.com/sallymwhitney, www.Twitter.com/1SallyWhitney, and www.Instagram.com/smwhitney65. |

Author to Author, a Conversation Between Eric D. Goodman and Sally Whitney

Fiction writers Eric D. Goodman and Sally Whitney were first published together in the 2007 anthology, New Lines from the Old Line State: An Anthology of Maryland Writers. Sally’s second novel, When Enemies Offend Thee, was released by Pen-L Publishing March 2020 and Eric’s fifth book, The Color of Jadeite, was published by Loyola’s Apprentice House Press October 2020. Both are interested in the other’s work, so they wanted to get together and talk about their new novels, writing processes, and what comes next.

Sally: In The Color of Jadeite, your descriptions of the Forbidden City, the Temple of Heaven, the Summer Palace and other locations are vividly detailed. I know you travel a great deal, and I think you’ve been to China. Have you visited the locations you describe or did you rely on research? Also, why did you choose to write about these particular locations?

Eric: Yes, the Chinese locations featured in The Color of Jadeite are all places I have visited. We spent a little more than two weeks exploring China, focused mainly on Beijing, Shanghai, and Xi'an with stops in Suzhou and Hangzhou. The architecture and culture seemed so exotic to me that even as we were touring I found myself thinking, "this would be a great setting for a novel" or "I have to set a scene here." The Temple of Heaven and Summer Palace, the Forbidden City and Terracotta Army—these were all places that simply amazed me when we were there taking it in, and they left an impression. That impression shows up all over this novel. I sometimes jokingly call this a "novel in settings" because part of my goal as I plotted out the novel was to get the characters to all of these locations I wanted to use not only as colorful backdrops, but as pivotal parts of the story.

Now, a question for you: When Enemies Offend Thee is your second novel. Did you change your writing process for book two, or did you find that your writing habits were very much the same?

Sally: I didn't really have a writing process when I started writing my first novel, Surface and Shadow. I had a setting that was important to me, a character who was important to me, and a nugget of a plot line when I plunged right in. As a result I had to make a lot of changes not only with revisions, but as I wrote the first draft. I had to combine a couple of characters and add a character who became critical to the story. I also deleted a lot of scenes. With When Enemies Offend Thee, I did much more planning before I began writing. I didn't do a detailed outline, but I did have a much greater sense of where the story was going and how. I didn't know how either book would end when I began writing, so that part of my process didn't change. And even with the increased planning of the second book, it took me the same amount of time to write it as the first.

Is this your first novel in which the story started with setting, or have you used that approach before in writing novels or short stories? I know setting frequently inspires my stories. What aspect of story-telling most frequently inspires your ideas?

Eric: Although setting is usually an important part to a story, often being sort of a character in itself, I normally don't start with setting as I did with Jadeite. Most often a story or book sparks from either an idea or a scene. I'll have a sort of vision of dialogue between two people, or think of a situation that seems interesting, and a story evolves from that. As an example, my novel Womb began with me pondering the most unusual narrator I could think of, and once I thought about the idea of an unborn narrator, the story grew from that simple idea. Setting the Family Free began with the real news story and then me imagining how the story unfolded differently for different people. Some of the stories from Tracks began with snippets of dialogue between people in certain situations that grew into stories and, ultimately, a novel in stories. I guess a story can come from anywhere, but for me it's normally either an idea or a specific scene.

You mentioned that setting often inspires your writing. Both of your novels take place in small towns. Is this a reflection of your own affinity for small towns, or a desire to introduce small towns to big-city-dwelling readers?

Sally: Surface and Shadow is set in a small mill town because part of my inspiration for the novel was to preserve the small-mill-town culture that flourished in the United States from the late 19th to late 20th centuries. By the year 2000, most small mills had been sold to larger manufacturers, and jobs were moved to larger cities or overseas. I grew up in that culture, and I wanted people to know what it was like, because once the mills were gone, the towns changed. In When Enemies Offend Thee, which takes place in 2011, I wanted to explore the ways the towns changed when the largest employer was no longer there. In the novel, the mental unease caused by lack of jobs plays an important role in shaping the characters and the plot. In both novels I also hoped to use the culture and customs of a single town to express a larger universal experience.

The Color of Jadeite is a noir detective story, which makes it different from your other novels. Why did you decide to pursue this type of fiction? Is it a genre you read often? What were its most challenging aspects to write?

Eric: Writing in this genre and voice was a fun challenge. I tend to read more literary fiction and mainstream fiction than noir detective novels, but I always did want to write an adventure story of this sort. The biggest challenge for me was probably plotting it out. Often, although I know where I'm headed, I feel my way through a novel. For this book, I had the entire thing plotted out in order to get the characters to each place, and coordinate who was where when (and who was alive or dead). With drama or literary fiction, I think there's more room to let your characters take you where they want. But with a thriller that involves multiple places and characters, I felt the need to map everything out ahead of time. That said, there was still room for unexpected dialogue and character traits to evolve unexpectedly.

Characters who “cross the line” after you fall in love with them can be fascinating. In When Enemies Offend Thee we follow Clementine as she begins going down a dark path, making decisions she never would have considered at the novel’s start. How did you navigate that path without sacrificing the readers staying “on board” with her decisions?

Sally: This is a great question because it goes to the heart of probably the biggest challenge I faced in writing When Enemies Offend Thee. I wasn't sure of all the things Clementine would do when I began the book, but that was one of my inspirations: to explore how far a person would go to right a wrong that had been done to her. My goal was to make her motivations so moving and believable that readers would understand her actions even if they didn't agree with them. I also used a lot of interior monologue to show what was going on in her mind, that she didn't come to some of these decisions easily. Her state of mind is critical to the story as she becomes more desperate when each plan fails. I wanted readers to feel empathy for her, and maybe a little respect for her courage, rather than judge her.

Eric: You certainly did a good job of putting us in her mind and making the reader understand her thought process as she made her decisions. In this way, I think she judged herself before the reader thinks to.

Sally: Thanks for your comment about conveying Clementine's state of mind. So far, most readers who've posted reviews did understand and empathize with her. A few, however, shared the concerns of one reader who said, "WHAT'S WRONG WITH THIS WOMAN?" in all caps just like that. Guess that was to be expected.

The plot of The Color of Jadeite includes searching for intriguing clues such as "where the chicken hangs, the frog bleeds" and objects like the cricket cage and coin. What process did you use to create the clues and decide on the objects? Were they part of your original plotting or did they come to you as you were writing? Do you have a favorite clue?

Eric: Yes, coming up with the clues was a fun and sometimes challenging part of the plotting. Most of the clues and the items they led to were part of the plotting, before the writing. Some didn't appear until my later drafts, or evolved from one thing to another. I tried to tie as many as I could to actual items we saw during our time in China that otherwise would not have made it into the plot—pet crickets and cricket fighting, clay barrels of rice wine, penjing trees in gardens, and terra-cotta warrior factories. I think my favorite clue was the last one, which managed to involve a misinterpreted translation, an image on Chinese currency, and a historic landmark all in one.

You describe Clementine’s antique shop so vividly that you can almost see, feel, and smell it. Did you have an actual shop in mind when writing? Did you find yourself going to antique shops more often to help with the descriptions?

Sally: Creating Clementine's antique shop was one of the easiest jobs I've ever had in writing fiction because I knew exactly how it looked, felt, and smelled. I've been an avid antiques collector for most of my adult life and have lingered lovingly in antique shops throughout the eastern and midwestern United States, as well as in Anchorage, Alaska, and on Portobello Road in London. I've often thought about how much fun it would be to own my own shop, so I indulged that fantasy through Clementine. The color of the walls, the selection of items, and the arrangement of items in her shop are very similar to what they would be if the shop were mine. I totally felt her love for her shop.

Each of the four main characters in The Color of Jadeite is distinctly different from the others. Why did you choose this particular mix of personalities? What does each contribute to the story?

Eric: That's an interesting question. I mentioned that the plot was well mapped out for this novel, but other areas evolved as I wrote. These characters are a good example of that. In my first draft it was just Clive and Wei Wei as the main characters, and Mackenzie remained in the states as a friend Clive called for help with the clues from time to time. I needed more interplay in the scenes, so in a later draft I brought Mackenzie in from the beginning and introduced Salvador. He was initially meant to be comic relief, but turned out to become a beloved character. And Mark is a fifth character who plays a larger role in the last half of the book. When there wasn't tension in the action, I tried to create tension between the characters: romance and uncertainty between Clive and Wei Wei, brother-sister-like love between Clive and Mackenzie, a sort of sibling rivalry between Salvador and Mark, a love-hate two-way street between Mackenzie and Mark, and a sort of sidekick loyalty between Salvador and Clive. These sometimes tricky relationships not only helped make the dialogue more interesting, it created opportunities for the characters (and readers) to place blame and suspicion.

Speaking of characters: Both of your novels feature strong female characters who have to fight their way through the challenges of a male-dominated society. What do you think makes a strong female character? To what degree do you feel women are challenged by these types of burdens today?

Sally: A strong female character is the same as a strong male character only more so. First of all, she's a human being with personal integrity and alliance to who she is. She's on a passionate journey to change the world or herself, even though she may not realize it. She has flaws that may make it difficult for her to accomplish the goal she seeks, but she also has the courage and wisdom to rise above those flaws. The reason she has to be more so than a male character is that society expects less of her and throws more obstacles in her way. Fortunately, this is less true now than it was in 1972 when Surface and Shadow takes place, but, as evidenced in the 2011 world of When Enemies Offend Thee, these problems continue, and they still exist today. While, unlike Lydia, married women today are able to get library cards—and credit cards and bank accounts—in their own names, they still make significantly lower salaries than their husbands and assume a greater responsibility for child care. Until these and other restraints are removed, women and literary heroines will have to fight harder for their accomplishments and to be the people they want to be.

Of all your novels, which was the hardest to write and why?

Eric: That's a tough one. Each novel has had its own set of challenges. For the novel in stories, it was finding as many subtle connections between the characters and stories as I could. For the novel in utero, it was the limitations of the perspective itself. For my last novel, Setting the Family Free, it was finding a multitude of different points of view for telling the story. But I would venture to say The Color of Jadeite, although my most traditional A-to-B novel, was the most challenging. This was in part because of the need to plot everything out ahead of time, and trying to keep the interactions of the characters and their logistics in balance. I found the organization of navigating the characters from one place and one clue to another to be challenging at times. But I'd do it again in a Shanghai second.

Your books are both entertaining and enlightening. They have strong characters, plots, and messages. Which of these elements spark the beginnings of a book for you—the seed? Which is most important when finishing a novel--the result?

Sally: Looking back at their beginnings, I feel like my stories were sparked by a swirl of ideas, but I realize that at their core, they started with a character. For Surface and Shadow, I wanted to write about a woman in the 1970s who wasn't sure whether the Women's Movement was a good thing but who knew something was wrong in her life. The 70s were a turbulent time for some women, and I wanted to explore that angst. For When Enemies Offend Thee, I wanted to write about a woman who realized nobody was going to help her right a terrible wrong that had been done to her. The events and additional characters that came to be the novels grew from those two women. At the end, the initial characters were still most important because they were the ones who conveyed the message.

The Color of Jadeite is a mixture of exciting action, luscious settings, and interesting history. What do you hope readers remember most about the novel?

Eric: It's funny, but I've gotten similar questions before worded in a different way and gave different answers. But because of the way you asked it, I realize that I should focus on the original inspiration for the novel: I hope readers come away with an appreciation of other cultures and a desire to learn more about the history and culture of new and exciting places. That, after all, is what inspired the novel to begin with—exploration of China and its culture and history and a desire to share it through a story. On a more basic level, this is a thriller, and I would be happy if readers simply come away feeling like they've had a good adventure, an enjoyable read, and gotten to know some interesting characters. Maybe some of whom they'd like to spend more time with in the future.

When Enemies Offend Thee is an interesting name, sounding almost like a quote from a poem or book. What inspired the title?

Sally: One of my favorite characters in the novel is Pete Ritchie, who owns the hardware store down the street from Clementine's antique shop. Pete is a somber fellow with a long, thin face, and his first reaction to the shop is that it'll never be a success, although he later becomes a supporter. One of his quirks is that he likes to quote Bible verses, most of which he misquotes. When he finds Clementine fighting back tears after an unpleasant encounter with Gary a few weeks after the assault, he tells her, “You know, it says in the Bible, ‘Tears wash misery from the mind, just as water washes dirt from the body.’ It’s good to cry every now and then.” Before he leaves the shop, his parting words are “The Bible also says, ‘Rise up with might when enemies offend thee. From the depths of retribution spring resolution and respect.’” He doesn't know it, but he's summed up much of Clementine's state of mind throughout the rest of the novel.

Eric: Yes, I remember that—I enjoyed his biblical-sounding quotes that were sometimes in no way biblical.

Sally: Final question: What are you working on next?

Eric: I'm finishing up rewrites on a short novel, or novella, called Wrecks and Ruins. It's sort of an anti-love story that ends up correcting itself. You may remember my short story that was published—along with your story—in the anthology of Maryland writers, New Lines from the Old Line State. My story, "Cicadas," was about a playboy who was resisting settling down during the cicada infestation of 2004. Recently I had been planning to write a story about a husband and wife who still love one another but aren't in love and who decide to divorce but remain friends. As the idea germinated, I realized not only that the next 17-year emergence of Brood X was coming in 2021, but that the characters from that story would be ideal in age and personality for the telling of this story. So although it began as an original idea, it ended up being a sequel of sorts. My ambition is to have Wrecks and Ruins out next year, with the actual cicadas serving as a backdrop.

How about you? What are you working on next?

Sally: My new novel explores the reactions of a group of parents when the best player on their sons' eighth-grade basketball team, who also happens to be the only Black player on the team, is seriously injured by a hit-and-run driver. Was the encounter strictly an accident? Or was it the result of community resentment against the newcomer who's overshadowing the town's native sons? Was one of the parents involved? It marks a return to Tanner, N.C., where Surface and Shadow and When Enemies Offend Thee take place, but this time it's 1984, and the townspeople are dealing with different kinds of changes.

# # #

Sally: In The Color of Jadeite, your descriptions of the Forbidden City, the Temple of Heaven, the Summer Palace and other locations are vividly detailed. I know you travel a great deal, and I think you’ve been to China. Have you visited the locations you describe or did you rely on research? Also, why did you choose to write about these particular locations?

Eric: Yes, the Chinese locations featured in The Color of Jadeite are all places I have visited. We spent a little more than two weeks exploring China, focused mainly on Beijing, Shanghai, and Xi'an with stops in Suzhou and Hangzhou. The architecture and culture seemed so exotic to me that even as we were touring I found myself thinking, "this would be a great setting for a novel" or "I have to set a scene here." The Temple of Heaven and Summer Palace, the Forbidden City and Terracotta Army—these were all places that simply amazed me when we were there taking it in, and they left an impression. That impression shows up all over this novel. I sometimes jokingly call this a "novel in settings" because part of my goal as I plotted out the novel was to get the characters to all of these locations I wanted to use not only as colorful backdrops, but as pivotal parts of the story.

Now, a question for you: When Enemies Offend Thee is your second novel. Did you change your writing process for book two, or did you find that your writing habits were very much the same?

Sally: I didn't really have a writing process when I started writing my first novel, Surface and Shadow. I had a setting that was important to me, a character who was important to me, and a nugget of a plot line when I plunged right in. As a result I had to make a lot of changes not only with revisions, but as I wrote the first draft. I had to combine a couple of characters and add a character who became critical to the story. I also deleted a lot of scenes. With When Enemies Offend Thee, I did much more planning before I began writing. I didn't do a detailed outline, but I did have a much greater sense of where the story was going and how. I didn't know how either book would end when I began writing, so that part of my process didn't change. And even with the increased planning of the second book, it took me the same amount of time to write it as the first.

Is this your first novel in which the story started with setting, or have you used that approach before in writing novels or short stories? I know setting frequently inspires my stories. What aspect of story-telling most frequently inspires your ideas?

Eric: Although setting is usually an important part to a story, often being sort of a character in itself, I normally don't start with setting as I did with Jadeite. Most often a story or book sparks from either an idea or a scene. I'll have a sort of vision of dialogue between two people, or think of a situation that seems interesting, and a story evolves from that. As an example, my novel Womb began with me pondering the most unusual narrator I could think of, and once I thought about the idea of an unborn narrator, the story grew from that simple idea. Setting the Family Free began with the real news story and then me imagining how the story unfolded differently for different people. Some of the stories from Tracks began with snippets of dialogue between people in certain situations that grew into stories and, ultimately, a novel in stories. I guess a story can come from anywhere, but for me it's normally either an idea or a specific scene.

You mentioned that setting often inspires your writing. Both of your novels take place in small towns. Is this a reflection of your own affinity for small towns, or a desire to introduce small towns to big-city-dwelling readers?

Sally: Surface and Shadow is set in a small mill town because part of my inspiration for the novel was to preserve the small-mill-town culture that flourished in the United States from the late 19th to late 20th centuries. By the year 2000, most small mills had been sold to larger manufacturers, and jobs were moved to larger cities or overseas. I grew up in that culture, and I wanted people to know what it was like, because once the mills were gone, the towns changed. In When Enemies Offend Thee, which takes place in 2011, I wanted to explore the ways the towns changed when the largest employer was no longer there. In the novel, the mental unease caused by lack of jobs plays an important role in shaping the characters and the plot. In both novels I also hoped to use the culture and customs of a single town to express a larger universal experience.

The Color of Jadeite is a noir detective story, which makes it different from your other novels. Why did you decide to pursue this type of fiction? Is it a genre you read often? What were its most challenging aspects to write?

Eric: Writing in this genre and voice was a fun challenge. I tend to read more literary fiction and mainstream fiction than noir detective novels, but I always did want to write an adventure story of this sort. The biggest challenge for me was probably plotting it out. Often, although I know where I'm headed, I feel my way through a novel. For this book, I had the entire thing plotted out in order to get the characters to each place, and coordinate who was where when (and who was alive or dead). With drama or literary fiction, I think there's more room to let your characters take you where they want. But with a thriller that involves multiple places and characters, I felt the need to map everything out ahead of time. That said, there was still room for unexpected dialogue and character traits to evolve unexpectedly.

Characters who “cross the line” after you fall in love with them can be fascinating. In When Enemies Offend Thee we follow Clementine as she begins going down a dark path, making decisions she never would have considered at the novel’s start. How did you navigate that path without sacrificing the readers staying “on board” with her decisions?

Sally: This is a great question because it goes to the heart of probably the biggest challenge I faced in writing When Enemies Offend Thee. I wasn't sure of all the things Clementine would do when I began the book, but that was one of my inspirations: to explore how far a person would go to right a wrong that had been done to her. My goal was to make her motivations so moving and believable that readers would understand her actions even if they didn't agree with them. I also used a lot of interior monologue to show what was going on in her mind, that she didn't come to some of these decisions easily. Her state of mind is critical to the story as she becomes more desperate when each plan fails. I wanted readers to feel empathy for her, and maybe a little respect for her courage, rather than judge her.

Eric: You certainly did a good job of putting us in her mind and making the reader understand her thought process as she made her decisions. In this way, I think she judged herself before the reader thinks to.

Sally: Thanks for your comment about conveying Clementine's state of mind. So far, most readers who've posted reviews did understand and empathize with her. A few, however, shared the concerns of one reader who said, "WHAT'S WRONG WITH THIS WOMAN?" in all caps just like that. Guess that was to be expected.

The plot of The Color of Jadeite includes searching for intriguing clues such as "where the chicken hangs, the frog bleeds" and objects like the cricket cage and coin. What process did you use to create the clues and decide on the objects? Were they part of your original plotting or did they come to you as you were writing? Do you have a favorite clue?

Eric: Yes, coming up with the clues was a fun and sometimes challenging part of the plotting. Most of the clues and the items they led to were part of the plotting, before the writing. Some didn't appear until my later drafts, or evolved from one thing to another. I tried to tie as many as I could to actual items we saw during our time in China that otherwise would not have made it into the plot—pet crickets and cricket fighting, clay barrels of rice wine, penjing trees in gardens, and terra-cotta warrior factories. I think my favorite clue was the last one, which managed to involve a misinterpreted translation, an image on Chinese currency, and a historic landmark all in one.

You describe Clementine’s antique shop so vividly that you can almost see, feel, and smell it. Did you have an actual shop in mind when writing? Did you find yourself going to antique shops more often to help with the descriptions?

Sally: Creating Clementine's antique shop was one of the easiest jobs I've ever had in writing fiction because I knew exactly how it looked, felt, and smelled. I've been an avid antiques collector for most of my adult life and have lingered lovingly in antique shops throughout the eastern and midwestern United States, as well as in Anchorage, Alaska, and on Portobello Road in London. I've often thought about how much fun it would be to own my own shop, so I indulged that fantasy through Clementine. The color of the walls, the selection of items, and the arrangement of items in her shop are very similar to what they would be if the shop were mine. I totally felt her love for her shop.

Each of the four main characters in The Color of Jadeite is distinctly different from the others. Why did you choose this particular mix of personalities? What does each contribute to the story?

Eric: That's an interesting question. I mentioned that the plot was well mapped out for this novel, but other areas evolved as I wrote. These characters are a good example of that. In my first draft it was just Clive and Wei Wei as the main characters, and Mackenzie remained in the states as a friend Clive called for help with the clues from time to time. I needed more interplay in the scenes, so in a later draft I brought Mackenzie in from the beginning and introduced Salvador. He was initially meant to be comic relief, but turned out to become a beloved character. And Mark is a fifth character who plays a larger role in the last half of the book. When there wasn't tension in the action, I tried to create tension between the characters: romance and uncertainty between Clive and Wei Wei, brother-sister-like love between Clive and Mackenzie, a sort of sibling rivalry between Salvador and Mark, a love-hate two-way street between Mackenzie and Mark, and a sort of sidekick loyalty between Salvador and Clive. These sometimes tricky relationships not only helped make the dialogue more interesting, it created opportunities for the characters (and readers) to place blame and suspicion.

Speaking of characters: Both of your novels feature strong female characters who have to fight their way through the challenges of a male-dominated society. What do you think makes a strong female character? To what degree do you feel women are challenged by these types of burdens today?

Sally: A strong female character is the same as a strong male character only more so. First of all, she's a human being with personal integrity and alliance to who she is. She's on a passionate journey to change the world or herself, even though she may not realize it. She has flaws that may make it difficult for her to accomplish the goal she seeks, but she also has the courage and wisdom to rise above those flaws. The reason she has to be more so than a male character is that society expects less of her and throws more obstacles in her way. Fortunately, this is less true now than it was in 1972 when Surface and Shadow takes place, but, as evidenced in the 2011 world of When Enemies Offend Thee, these problems continue, and they still exist today. While, unlike Lydia, married women today are able to get library cards—and credit cards and bank accounts—in their own names, they still make significantly lower salaries than their husbands and assume a greater responsibility for child care. Until these and other restraints are removed, women and literary heroines will have to fight harder for their accomplishments and to be the people they want to be.

Of all your novels, which was the hardest to write and why?

Eric: That's a tough one. Each novel has had its own set of challenges. For the novel in stories, it was finding as many subtle connections between the characters and stories as I could. For the novel in utero, it was the limitations of the perspective itself. For my last novel, Setting the Family Free, it was finding a multitude of different points of view for telling the story. But I would venture to say The Color of Jadeite, although my most traditional A-to-B novel, was the most challenging. This was in part because of the need to plot everything out ahead of time, and trying to keep the interactions of the characters and their logistics in balance. I found the organization of navigating the characters from one place and one clue to another to be challenging at times. But I'd do it again in a Shanghai second.

Your books are both entertaining and enlightening. They have strong characters, plots, and messages. Which of these elements spark the beginnings of a book for you—the seed? Which is most important when finishing a novel--the result?

Sally: Looking back at their beginnings, I feel like my stories were sparked by a swirl of ideas, but I realize that at their core, they started with a character. For Surface and Shadow, I wanted to write about a woman in the 1970s who wasn't sure whether the Women's Movement was a good thing but who knew something was wrong in her life. The 70s were a turbulent time for some women, and I wanted to explore that angst. For When Enemies Offend Thee, I wanted to write about a woman who realized nobody was going to help her right a terrible wrong that had been done to her. The events and additional characters that came to be the novels grew from those two women. At the end, the initial characters were still most important because they were the ones who conveyed the message.

The Color of Jadeite is a mixture of exciting action, luscious settings, and interesting history. What do you hope readers remember most about the novel?

Eric: It's funny, but I've gotten similar questions before worded in a different way and gave different answers. But because of the way you asked it, I realize that I should focus on the original inspiration for the novel: I hope readers come away with an appreciation of other cultures and a desire to learn more about the history and culture of new and exciting places. That, after all, is what inspired the novel to begin with—exploration of China and its culture and history and a desire to share it through a story. On a more basic level, this is a thriller, and I would be happy if readers simply come away feeling like they've had a good adventure, an enjoyable read, and gotten to know some interesting characters. Maybe some of whom they'd like to spend more time with in the future.

When Enemies Offend Thee is an interesting name, sounding almost like a quote from a poem or book. What inspired the title?

Sally: One of my favorite characters in the novel is Pete Ritchie, who owns the hardware store down the street from Clementine's antique shop. Pete is a somber fellow with a long, thin face, and his first reaction to the shop is that it'll never be a success, although he later becomes a supporter. One of his quirks is that he likes to quote Bible verses, most of which he misquotes. When he finds Clementine fighting back tears after an unpleasant encounter with Gary a few weeks after the assault, he tells her, “You know, it says in the Bible, ‘Tears wash misery from the mind, just as water washes dirt from the body.’ It’s good to cry every now and then.” Before he leaves the shop, his parting words are “The Bible also says, ‘Rise up with might when enemies offend thee. From the depths of retribution spring resolution and respect.’” He doesn't know it, but he's summed up much of Clementine's state of mind throughout the rest of the novel.

Eric: Yes, I remember that—I enjoyed his biblical-sounding quotes that were sometimes in no way biblical.

Sally: Final question: What are you working on next?

Eric: I'm finishing up rewrites on a short novel, or novella, called Wrecks and Ruins. It's sort of an anti-love story that ends up correcting itself. You may remember my short story that was published—along with your story—in the anthology of Maryland writers, New Lines from the Old Line State. My story, "Cicadas," was about a playboy who was resisting settling down during the cicada infestation of 2004. Recently I had been planning to write a story about a husband and wife who still love one another but aren't in love and who decide to divorce but remain friends. As the idea germinated, I realized not only that the next 17-year emergence of Brood X was coming in 2021, but that the characters from that story would be ideal in age and personality for the telling of this story. So although it began as an original idea, it ended up being a sequel of sorts. My ambition is to have Wrecks and Ruins out next year, with the actual cicadas serving as a backdrop.

How about you? What are you working on next?

Sally: My new novel explores the reactions of a group of parents when the best player on their sons' eighth-grade basketball team, who also happens to be the only Black player on the team, is seriously injured by a hit-and-run driver. Was the encounter strictly an accident? Or was it the result of community resentment against the newcomer who's overshadowing the town's native sons? Was one of the parents involved? It marks a return to Tanner, N.C., where Surface and Shadow and When Enemies Offend Thee take place, but this time it's 1984, and the townspeople are dealing with different kinds of changes.

# # #

| Miriam Edelson is a neurodivergent social activist, writer and mother living in Toronto, Canada. Her literary non-fiction, personal essays and commentaries have appeared in The Globe and Mail, Toronto Star, various literary journals including Dreamers Magazine, Collective Unrest, Writing Disorder, Palabras, Wilderness House Literary Review and on CBC Radio. Her first book, “My Journey with Jake: A Memoir of Parenting and Disability” was published in April 2000. “Battle Cries: Justice for Kids with Special Needs” appeared in late 2005. She has completed a doctorate at University of Toronto focused upon Mental Health in the Workplace and is currently at work on a collection of essays. She lives with and manages the mental health challenges related to bipolar disorder. |

Driving Miss Emma

My daughter Emma is straining to craft an identity separate from me. At 27, she is achieving this as she forges her life’s path. I admire that she is creating, designing with raw materials, making objects with her hands that are functional as well as beautiful. So different than my own, with its emphasis on the written word.

My girl is a woodworker, making her way in a world of craftsmanship. I trail behind her in the exotic wood emporium we visit occasionally to pick up her supplies. Proud as a peacock I watch her assessing the wood that she needs, measuring and sawing boards on forbidding, noisy machines. Cutting quite the figure in her tool belt and blue overalls, she tells me about the wood she has selected, the maple and softwoods and, of course, the burled wood on display.

She is now launched, mostly independent. There is some feeling of loss for me, but moreover, a feeling of pleasure and accomplishment that she has reached this moment. At home my kitchen, I touch a piece of jute cord that appeals to me in its sturdiness and heft. At one time, the link between Emma and me was strong and unbreakable like the rough, jute cord. Time passes and she matures, and she needs a less robust link with me to develop into herself. A soft yarn then serves to connect us. She thrives as the connection is lessened, until eventually, only a fine diaphanous thread dangles between us. Still enduring but not nearly so hefty or fragile.

Suddenly I recall that when she was a young girl, maybe six or seven years old, she was like my little sidekick. That changed over time, as her friends became more important to her. But I adored that closeness, “Oh Mommy, I have so much to tell you” she would say. I was her first confidante.

Now, I am not. And so, I strive to let go and to find my own place in this reconstituted order. I cradle a piece of burled wood in my city girl hands. Originating from a tree that was stressed, it is a round knotty growth that when polished will be full of swirls and beauty. I peel away the bark to investigate and marvel at the entangled splendour underneath. Craftspeople say that it can take thirty years for its full beauty to emerge.

The swirl of my burl is my life stories, my children, my joy and pain. Through my writing I shine a light on that jumble of memory, fact and emotion, searching for truth. Like my stories and myself, the burl wood grain is twisted and interlocked, resistant to splitting. I look upon it with wonder as it teaches me to find strength in its misshapenness.

I need that strength. In my interactions with my Emma I am constantly trying not to overstep, to respect the boundaries that she erects. It can be painful. Sometimes the edges feel like barriers but they can also melt away, as malleable as the situation commands.

***

I pick Emma up at the subway near my home. She is waiting there, slim, light brown hair tossed by the wind. It’s a late September day as we set off for Ithaca, New York in the Finger Lakes District, about four hours from Toronto. Anticipating almost two weeks together for adventure, family and travel, we are both in good humour and easy with one another.

This has not always been the case. Earlier this year she pulled sharply away from me, not wanting any contact over a period of a few months. She was angry about something I’d done. It was a very painful interval, for both of us. By the time our road trip began we had healed somewhat, taken to seeing one another again and sharing aspects of our lives. The trip, I hope, will be a chance to cultivate and deepen our ease with one another.

The chair Emma designed and crafted, the primary reason for our trip, is braced safely in the back of the car. She conceived and built it at Sheridan College where she studied furniture craft and design. It is a unique piece, with an almost Scandinavian air, a fully wooden seat with no weaving or thatch. A beautiful, original rendering, it is now covered with care by an old grey baffled blanket. It awaits delivery to an exhibit space in Philadelphia. We wonder what we’ll be asked at the border, but they say nothing about the chair when I tell them we are on our way to visit my brother’s family there.

We meet my niece Sarah in Ithaca, where she is doing a doctorate in psychology at Cornell. First, we stop at the little air bnb I’d reserved and drop off our things. Then we walk along a few tree-lined streets to the famed Moosewood Restaurant. Sarah is gracious. Seven months pregnant, red-haired and still generously freckled, she seems quite radiant over dinner. As imagined, the vegetarian food is tasty and wholesome, a Seventies throwback for sure. I have most of their cookbooks and cherish fond memories of cooking from them in a co-op house with friends while at university.

We talk about Sarah’s program of study and how she expects they will manage the baby’s first year, with her husband Peter still in Philadelphia. She is upbeat and looking forward to the challenges ahead. Emma tells her about the chair and also the woodworking course she will be doing in Maine in another week’s time. I am pleased to see Emma and Sarah kibitz and bond together during our dinner. We haven’t always had close relations with their family and I hoped Emma would feel closer to them. When we’re saying goodbye, Emma buys a pale green baseball cap that sports the Moosewood logo, and Sarah wishes us good luck for our upcoming visit with her parents in Philly.

We blow in to Philadelphia the next day about four in the afternoon, just as Speaker Nancy Pelosi is declaring publicly for the first time that the U.S. House of Representatives will engage in impeachment hearings of the president. My brother is glued to the television, citing the historic moment, only moving slightly to snarl at me that I shouldn’t have parked where I did. Lynne, his wife, makes soothing noises and the exchange does not boil over, as it often does. I move the car.

Emma and Lynne ferry the chair to the garage where it can continue to off-gas from its finishing products. We offer to help with dinner but are shooed away to our respective rooms to rest. Emma looks up a climbing gym nearby on Google maps and catches an Uber to work out for a couple of hours. Later, Lynne and I go for a much-needed invigorating walk in the community before dinner. Lots of old leafy trees and wide lawns are welcome indeed after two days of stressful highway driving. We work up a little sweat and the exercise helps bring me back down to earth. We talk about our kids, their lives and a little bit about the challenges of relationships with our respective partners.

The next morning, after a delicious breakfast of coffee, fresh berries and yogurt, we head into Philadelphia to deliver the chair. Lynne offers to drive, and so I do not need to navigate the city’s busy streets. We drive to the Center for Art in Wood in downtown Philadelphia. The Center interprets, nurtures, and champions creative engagement and expansion of art, craft, and design in wood. It is a beautiful, bright venue. Emma does a little dance on the sidewalk with the chair held up in her arms and we follow her in, Lynne and I snapping photos all the way. We joke that we are her “paparazzi” and the Center staff laugh as we enter. Mission accomplished. The chair is delivered safely to the show “Making a Seat at the Table: Women Transform Woodworking” and we can continue on our journey.

We spend another relaxing night at my brother’s having a barbecue dinner out on the patio, and then set off the next day toward upstate New York where we will visit Storm King Art Center. It is a 500-acre outdoor museum located in the Hudson Valley, where you can experience large-scale sculpture under open sky. Since 1960, Storm King has been dedicated to stewarding the hills, meadows, and forests of its site and surrounding landscape. We walk through the countryside looking at the huge sculptures and learn how the facility nurtures a vibrant bond between art, nature, and people, creating a place where discovery is limitless. It is a fabulous afternoon in the open air.

The next day we venture to the gallery known as the Dia Beacon, also in upstate New York. Located in a former Nabisco box-printing factory, Dia Beacon presents Dia’s collection of art from the 1960’s to the present. It is a spacious gallery with very high ceilings and many impressive installations. We are playful, both enjoying this, as we snap photos of one another as we walk about the gallery. We’re having fun.

Emma is most taken by the work of American artist Richard Serra. Serra is one of the preeminent American artists and sculptors of the post-Abstract Expressionist period. His large-scale steel panel welded sculptures are remarkable and he suggests that art should be something "participatory" in modern society, that is, a gesture, or physical insertion into everyday life, not something confined to a cloistered museum space. “I love how you have to interact with his pieces and how sound, vision and space changes your mood depending on the undulations of each piece,” Emma wrote to me in answer to my questions about Serra. “Once when I was in Portugal where one of his large pieces is found, people were singing within the centre of the sculpture and it totally changed the experience.”

The following morning, we make our way to visit the Shaker Village in Hancock, Massachusetts. It is a former Shaker commune that was established by 1790 and active until 1960. It was the third of nineteen major Shaker villages established between 1774 and 1836 in New York, New England and other states. It is a nice day and we explore the different buildings and also walk on a path into the woods at the side of the village. The buildings represent all the trades that would have contributed to the village’s commerce, including a hardware shop and blacksmith. Emma looks carefully at the tools in the woodworking shop.

Then we head off to Boston to see another of my nieces, Kaitlyn and her family. She is Sarah’s older sister. It is not an easy drive into the core of the city where they live. Some of the time, Emma is irritated by my weaknesses. We’re in a busy parking lot. It’s early evening and I’m having trouble seeing the parking signs. I have to rely on her to point them out. “I practically have to drive the damned car,” she charges. So, I’m not perfect, I think to myself. I wish she was more generous in her attitude toward me. Besides, she could learn to drive!

We park on their street and meet Kaitlyn and Paul at home and have drinks and snacks together on the balcony. It is a pleasure to play with Maya, who is coming up to two years old. Kaitlyn, an obstetrician herself, is pregnant with their second child, and that makes for some interesting conversation as they wonder how they will fit everyone into their modest apartment. It was great to see Emma connect with Kaitlyn and I feel that one of my goals for the trip has been met. Adult friendships have been rekindled with her cousins. I hope they will keep in touch in future. Later we walk to a family restaurant and have a nice meal, before saying goodnight and returning to our air bnb.

We then have a two days’ drive to Maine. I think a lot about my relationship with Emma and the tensions between us. We talk a little, but nothing earthshattering. That night we stay at a non-descript motel just off the highway. Emma goes to a climbing gym, leaving me to get settled and do some writing.

When she gets back she looks at me and says suspiciously, “Did you take something? Your pupils are so dilated.” I feel hurt and say, “No, of course I haven’t”. I’m just feeling exhausted from all the driving and I suppose it shows in my face. I wonder if she thinks I’ve taken my medications incorrectly. We amble over to the little store next to the gas station to pick up a few items. I am still smarting from her accusation. She seems to settle down after that, but we don’t talk about her hurtful remarks. I cannot cross the boundary line she has erected without fear that I might lose her again. The lack of power I assign myself in the situation saddens me.

The reason Emma chose to be so distant from me last year stems from a first-person piece that I broadcast on public radio about my battles with depression. I had disclosed a suicide attempt that I made when Emma was just a few months old. Unfortunately, I did not prepare her adequately for the broadcast and so it was the first time she heard of it. She was both hurt and angry at me and wanted to know why I had not told her this before. I felt awful about it, not quite believing myself that I’d been so negligent not to tell her in person about that dismal period, before it was broadcast to the world. But I was trying to protect her at some level, and it backfired. Big time. I did not know, during those awful months of separation, if I would ever get her back.