Detained in Tehran—Sort OfThe timing of the call could have won an award for serendipity. I was walking the halls of the former U.S. embassy in Tehran, nicknamed Henderson High by the former diplomatic staff because of its resemblance to American high schools of the 1940s, when it was built. Now it is the Museum of Anti-American Arrogance, since it reopened to display the alleged subterfuge of American diplomats before the fall of Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi.

It was Firouzeh’s phone that rang. For three days Firouzeh had been my guide in Tehran, leading me around the sights of the city. The call ended, and she told me that when we were finished she had been instructed to bring me to the visa office. I didn’t know, but soon learned, that within the Iranian foreign ministry there is a special department that approves (or denies) visas for the “usual suspects” (from the Iranian point of view)—Americans, Canadians, and citizens of the United Kingdom—who are required to be accompanied by a tour guide from the beginning to the end of their stay in Iran. We spent the next half hour strolling through the grim corridors, eyeing the massive office machines, circa 1979, which the regime claims as proof of the effort of a global power to “meddle in the internal affairs” of a smaller one. Which was probably true. But whether all of this was evidence of “crimes against Iran” or merely the electronic gadgetry any embassy would have had on hand to do its business, circa 1979, was anyone’s guess. The visit over, we headed to the main gate. As we left the ticket seller, with customary Persian hospitality, wished me a very pleasant stay in Iran. When we entered he’d asked Firouzeh where I was from. “Welcome home,” he’d replied. Our driver was waiting at the gate. Firouzeh had summoned him. We navigated the Tehran traffic for half an hour before pulling up in front of a drab, nondescript office building. Nothing stated its purpose. It could have been a department of the foreign ministry or the office of an insurance company. The interior was just as drab. Drabness is the face of bureaucracies because drabness makes no statement. It says nothing about its modus operandi, least of all its character or values, if it has any. But drabness takes on special meaning in Iran. Because drabness says nothing it can say anything, and in Iran any statement—of aim, of intention, of principle—depends on circumstances, which are forever changing. Therefore the bureaucracy, and those who administer it, may alter its face at a whim, because they, too, have made no statement, staked no claim, said nothing. In the Persian mind clarity limits flexibility, offers no wiggle room, no opportunity to adjust to changing circumstances. One needlessly boxes oneself into a corner. It is bad politics, bad negotiating strategy, bad everything when delicate relationships are in play. Firouzeh was told to wait outside. I handed over my cell phone and passed through the metal detector and spent the next 10 minutes sitting on a drab waiting-room chair waiting for—I knew not what. Finally I was called to an inner office. A tray of Persian sweets was centered on a coffee table surrounded by leather couches. I sat down to wait. An office lackey brought me a cup of tea with a mountain of sugar cubes. The cubes were provided so the tea could be drunk the Persian way—sucking it through a single cube, placed between the teeth. After a few minutes two officials entered—a 30-something I will call Amir and an older man with a salt-and-pepper beard and hair to match I will call Reza. Amir sat on the couch across from me. He had a scholarly look, with horn-rimmed glasses and thin build. But Reza established himself as the boss by seating himself behind the only desk in the room. “Are you aware of the reason for this?” Amir asked with easy, Persian formality. I shook my head. “No.” “We have many foreign tourists and like to learn about their interest in our country. We realized you were leaving Tehran tomorrow and wanted the opportunity to meet you. We have many Americans but not many who come in Iran three times.” Of course this was horseshit. If the visa office wanted to meet every foreign tourist who came to Iran it would have to book appointments. Likely they realized only that afternoon that I was scheduled to leave Tehran the next day and told Firouzeh to hustle me over to the visa office before I was “on the road”—Iranian style. But why? Because few Americans visit Iran three times, if at all, and my repeat visits had made them curious. Reza and Amir tried to wear the garb of gracious Persian hosts, but it was costume that did not fit. To get ahead of them I explained my interest in the country. For years I’d read articles about Iran that portrayed a much different reality than anything conveyed by conventional news outlets. In 2004 I moved to the UAE and one of my aims was to see it firsthand. The conversation shifted to my first visit to Iran, during the postelection demonstrations in 2009. Violent demonstrations rocked the streets of Tehran and other cities, because former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was reelected to a second term due to poll results widely seen as fraudulent. “Weren’t you frightened?” Amir asked. “Not really.” “No?” “No. I grew up in Chicago in the middle of the civil rights movement. It was the violent sixties, and there were lots of protests over the Vietnam War.” It was not the answer they expected. Americans are supposed to be afraid to leave their comfort zone, fear places in the world viewed as threatening. “Didn’t you think someone might attack you, being an American?” I shook my head. “Iranians aren’t violent, and they like Americans.” Reza was listening close, but turned to Amir for a translation. Then he sat back in his chair, revealing nothing. Amir then wended his way through a series of questions he already knew the answers to: How long had I lived in the UAE? In what area did I teach? In classic Persian style it followed no particular path and was aimed in no particular direction, like all good conversations. But it clearly had one, otherwise I wouldn’t have been summoned to the visa office the day before I was supposed to leave Tehran. Whatever it was, only Reza and Amir held the keys, but even they may have had no clear aim other than to “feel out” this American on his third visit to Iran. What did I think of Trump’s decision to move the American embassy to Jerusalem?—Amir asked. It was a mistake. Jerusalem should become a neutral city, shared by all the major religions. Did I believe in God? How we arrived at this is lost within a series of steps that left no trace, but I found the winding, twisting course of the conversation fascinating. In the traditional sense—no. As a Syrian friend of mine once said about religion, “I believe in all of them and none of them.” But, I added, just to throw a spanner into the works—I was part Native American, and I’d always felt drawn to Native American spirituality. Reza leaned forward to listen close, but far more important than my responses was tone and body language, which needed no translation. Sometimes I sat back in the couch, sometimes I leaned forward—whatever suited the moment. That I taught university-level writing courses also interested Amir: Did I have a Web site? A blog? “No.” “No?!” No. I told him I had neither the time nor interest. “I have always been under the impression that writers feel their work has to make an impact, socially or politically.” “That’s more true of Europeans,” I explained. “European writers have a much longer history of social and political activism. They’ve had more revolutions. It happens in the U.S. too, but usually among minorities and other groups, or during times of conflict. Many writers have strong views, but in America it isn’t seen as obligatory to use writing for that purpose.” All of this was translated for Reza, who nodded with each phrase Amir sent his way. I enjoyed the mini-lecture on American letters. It turned the tables, if briefly. Iranians are masters of obscurity—in language, thought, even purpose. But here was a straight-talking American they could not quite figure out. Amir recalled what I’d said about film studies being my main area of teaching. He asked if I knew much about Iranian cinema. “It was excellent,” I replied, which was certainly true, and I rattled off a string of films I admired-- The Color of God, by Majid Majidi, Leila, by Dariush Mehrjui, A Taste of Cherry, by Abbas Kiarostami, and of course Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation and The Salesman. For the first time Reza cut in, without translation: “You like the ones with all the beautiful women.” “Who cares about the men?” I shot back. There was a round of laughter. When it died down Amir asked if I found the Iranian people hospitable. “Very much,” I replied, which was also true, “but they can’t beat the Syrians.” Amir was nonplussed: “The Syrians are more hospitable than us?!” “Yes, but don’t take it personally. No one can beat the Syrians.” Another round of laughter. It had become clear this was not going to be a short conversation. I thought of Firouzeh waiting outside and hoped she’d found a coffeeshop nearby to kill the time sipping a cappuccino. Amir asked to see my passport. I told him I’d given it to the reception desk at the hotel when I checked in and never got it back. This threw them into a minor tizzy. I was supposed to have it in my possession all the time in Iran, he scolded—slightly. Reza summoned the tea lackey, issued instructions, and he left the room. And then, without any explanation, Amir left also. Then it was only Reza and me in the drab surroundings. Reza leaned back in his chair and rocked slightly, avoiding eye contact. Time passed—15 minutes, then 20. I wanted to engage him, seek tips on the best coffeehouses in Tehran, or where to find the best pizza—anything to fill the silence—but his English was not up to the task. That had been Amir’s job—to serve as translator and questioner. Time passed, and I wondered what the point of this was—the wait. Was it calculated? Very little in the Iranian mindset isn’t calculated. Like all good chess players, they make no move without thinking five steps ahead. To paraphrase Barack Obama, Iranians “don’t do stupid stuff.” They may blunder, like all good chess players, but impulsiveness is a rare find in the Iranian gene pool. So I waited—for Amir or the lackey to return with my passport so we could get on with it. So I could head back to the Hafez Hotel, put my feet up, and watch a bit of Press TV, the English-language Iranian satellite network. I wondered what Reza was waiting for. That I’d crack under the pressure, reveal the true reason for my return to Iran? That would be the tactic of any interrogation, but this wasn’t an interrogation—or was it? When Amir first settled down on the couch across from me he said, straightway, that if I felt uncomfortable about the meeting I was free to leave and go on with my sightseeing. And he meant it. But I wasn’t uneasy and had no reason to be anywhere else. Besides, whatever was about to transpire was far more interesting than anything that could be found in another Tehran museum. One of the purposes of museums is to project clarity—historical, cultural, scientific. Here nothing was clear, not the aims of Reza and Amir, nor the reason for my presence, nor the possible endgame, which made this more enthralling than any museum could ever be, and it give me a better insight into Iran than any museum could. After 20 minutes Amir reappeared, holding my passport. I was impressed. The lackey must have zipped through the Tehran traffic on his motorbike in record time, flashed whatever credentials he needed to obtain it from the hotel staff, and done double-time all the way back. Reza took the passport and flipped through it. It was cluttered with a dizzying array of visa stamps and entry and exit permits, which said as much about my travel patterns as a jumbled Rubik’s cube. Reza tossed it on the table. I looked at the clock. It was almost five-thirty. Again I thought of Firouzeh, and wondered if she wondering if I had been carted away to Evin Prison or some holding tank within the labyrinth of the Iranian penal system, and if I had, what would she do? But there was no reason for worry. Our chat was at an end. Both Reza and Amir rose, and with consummate Persian politeness shook my hand and wish me a very pleasant stay in Iran. Amir added, in a moment of rare candor, “We had no idea it would go on this long, but it was so interesting!” I’m sure. And with that I left. Regrettably, Firouzeh hadn’t been whiling away the time in a coffeeshop. She was so unnerved she hadn’t left the car for the past two hours, now waiting outside the office door. The driver flashed his lights and I got in. “When you didn’t come out I didn’t know what to think,” Firouzeh stammered. I was about to fill her in on the curvaceous conversation, but she had other things on her mind. “Did they ask about me?” “No.” “Every day we just followed the program, what the agency gave me,” she argued, defensively, and she opened a plastic binder to show me the itinerary she had been handed. It was all written in Farsi and meant nothing to me, but her worry was clear. Had we strayed from it in any way and had there been questions about it, it was she, not me, who would have had questions to answer. But Reza and Amir weren’t interested in where I had gone or what we had done, and probably knew anyway. To put her mind to rest, I gave her a quick rundown on my conversation with Reza and Amir in all its mundane detail—banality is often a balm for anxiety. Soon we were turning off Ferdowsi Street and pulling up in front of the hotel. I got out of the car and thanked her for her very professional service over the past three days. The worry lines on her face had smoothed—a little. The next morning I was greeted by a new guide, Aydin. After breakfast we loaded his car and headed northwest, spent three days in Tabriz before making an abrupt right turn at Ardabil to cruise toward Rasht and Ramsar, on the Caspian coast. All was smooth going. Then we got to Rasht. The night we arrived there were antigovernment demonstrations on the streets. In the past few days they had erupted in many cities, but oddly, many were known to be government strongholds. Tehran, usually the hotbed of antigovernment sentiment, was left in the cold. Even by Iranian standards it was curious—forever curious. Aydin and I had dinner at an Italian restaurant and then took a stroll along the pedestrian streets for which Rasht is well known. The shops were alit and buzzing. Then progovernment demonstrators appeared, parading down the center of the street, escorted by security forces and mouthing pro-regime slogans. Politically speaking, it was a muddle—pro-regime voices shouting down protestors who were also attacking the government? Pundits speculated that it was all a stage show, that the antigovernment protests had been organized by anti-Rouhani forces aiming to blemish his too-liberal government, and the harder hardliners had taken to the streets not to support Rouhani, but to bolster their allies seeking to humiliate him. In the end the guessing game continued. No one knew anything. The next day Aydin’s phone rang. We were on the highway somewhere between Rasht and Ramsar, with the azure sheen of the Caspian glimmering to the east. I identified the voice on the other end as the woman from the tour agency who had met me at my hotel in Tehran one morning to collect the payment for the trip. She had called a few times before, but this was the first time since the Rasht episode. The two chatted, I heard laughter, and when Aydin hung up I asked, “Was that the office again?” He sighed. “Yes . . .” “What did they want?” He fessed up. The agency had been calling him two, three times day, he said, sometimes first thing in the morning, sometimes late at night, at least once in the middle of the day: How is everything going? Have there been any problems? This time they wanted to know about the night before. “What did you tell them?” “That we went for a walk and there was a demonstration.” “What did she say?’ “She just laughed and asked, ‘What did you do? I told her—we watched it go by.” And that was that, and other than that I knew nothing, and neither did Aydin. Perhaps the visa office had instructed Hamid, the tour agency’s man-in-charge, to check in on me. Perhaps Hamid had taken it upon himself to check in on me, to ensure he had nothing to report to the visa office should it call to check in on me. Either could have been true, or not. In Iran one learns to work with a limited horizon. It is like forever driving on a foggy night with the headlights going dim. The trip finished, and a few months later I contacted Hamid. Could he arrange another visa for me? The timing was bad, and I knew it. The U.S. had just pulled out of the 2015 nuclear deal—that was a fact—and likely the Iranians weren’t very anxious to welcome an Americans, even a returnee. But Hamid passed my request on to the visa office anyway. A few days later he replied. “You are very famous to them,” he wrote back. No kidding. But then he went on, with practiced Persian regret, to say that the foreign ministry would not give me another visa—not now. It might approve one “in the future, after a while.” But—he made clear—they gave no indication of what “a while” meant, and “might” only guaranteed that there was no guarantee, but it didn’t close the door, either. I couldn’t have expected anything else—a reply that was forever obscure, perfectly noncommittal, classically Persian. As an Iranian friend of mine once said, “Who would be stupid enough to tell anyone exactly what they think?”

0 Comments

Journey to the Kagayaku Smile |

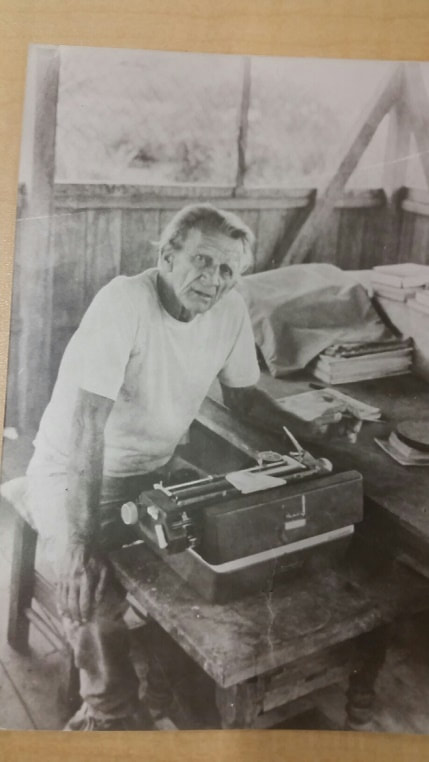

| Charles Hayes, a multiple Pushcart Prize Nominee, is an American who lives part time in the Philippines and part time in Seattle with his wife. A product of the Appalachian Mountains, his writing has appeared in Ky Story’s Anthology Collection, Wilderness House Literary Review, The Fable Online, Unbroken Journal, CC&D Magazine, Random Sample Review, The Zodiac Review, eFiction Magazine, Saturday Night Reader, Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, Scarlet Leaf Publishing House, Burning Word Journal, eFiction India, and others. |

You’ll Be Sorry

After passing over the coastal mountains along the South China Sea we went into a sudden dive, sending my stomach up to my throat. Out the small bulkhead window I saw the jungle and bamboo villages suddenly grow larger until, just as suddenly, we pulled up. Palm trees flashed by just below the wings. I checked my crotch for wetness and watched the palm trees quickly give way to black tarmac. We landed hard and slowed just enough to quickly exit the runway and taxi to a large metal hanger. As if this was all completely normal, a colorfully dressed stewardess appeared at the front of the cabin and welcomed us to the busiest airport in the world, Da Nang, Vietnam.

I came from one of the many sweeps for poor white trash and blacks conducted throughout Southern Appalachia to feed the Vietnam war. Having no clout nor any real means to get out of the poverty of the hills or avoid the draft, I was easy prey for the “Uncle Sam Wants You” roughriders at my local draft board.

I reported for induction into the Army and the sergeant in charge told me that the Marines were short on men. He said that if I agreed to join them for 3 years I wouldn’t have to go to Vietnam. Otherwise, the sergeant said that I would be beating the Vietnam bush within 3 months. I fell for the spiel, beginning a journey that still quickly took me to Vietnam. Taking a last look back at the pretty stewardess standing in the exit doorway I said my goodbyes to the world.

The first thing I noticed after that goodbye was the heat coming from all directions as it poured down and was reflected back by everything it touched. Everyone seemed to be in motion as if the sun demanded it in order to avoid being cooked dry by its wash.

My group was quickly met by a gunnery sergeant as he hopped out of a jeep, gathered us together, and herded us toward our next staging area. All along the hot tarmac I could see camouflaged jets landing and taking off. The same for helicopters. It was one big beehive of sweat, flashing afterburners and noise.

Soon we passed another group of marines peering at us through a chain link fence just off one side of the tarmac. Looking very much out of place amongst all the purposeful activity and uniform dress, they wore jungle fatigues and floppy bush hats. With their jungle boots scuffed tan from wear and never having seen any polish, their gaunt yellowish faces, colored by the anti-malaria pills, they looked out from masses of long hair and mustaches. But it was their eyes and demeanor that really set them apart and belied their youth as they amused themselves, watching the new guys as if watching their favorite animals at the zoo. Pressed up against the links in the fence, like some band of detainees curtained off from the more respectable lots of society, their looks unsettled me in a way that’s hard to explain. Like I was part of some exhibition of the condemned. I wanted to ignore them but couldn’t help staring back. Reviewing their faces, I saw that most seemed to be there just for the sake of being there. No particular reason or motivation registered on their visages, just that they were there and accounted for, to hell with anything more definitive than that. That was until I met the eyes of one a little taller and dirtier than the rest. With no amusement reflected in his dark eyes, he sang out in a clear lilting voice without a hint of comedy, “You’ll…….. be…… sor……ry.” The others along the fence only stared on as if the tone of his prediction rang with an air that some things just were ...and not a one of them doubted it.

We eventually got parked in a huge hanger and over the next few hours were in turn sent out over Vietnam far and wide to replace those who were going home, or who had been killed or wounded. When it came to my turn I was sent only a few miles southwest of the air strip.

I was very much welcomed when my jeep arrived at my new unit. No predictions of sorrow were heard for me who had come to freshen up this unit. Fresh newbies generally meant a little less hazard for those trying to get out of the Nam someway other than a crate or a hospital plane. Making it through that year and getting the hell out of there was what it was all about. Not complicated at all I soon figured as I settled in and started ticking the days until I could get back to the world. Nor was it complicated or long before I got my first taste of the war, that cherry from the hillbilly country of West Virginia.

As the pop flare drifted to earth a ghostly light was cast over the green wet terrain beyond the perimeter of the 1st support battalion, 1st Marines. Those along the bunker line facing the base of Hill 821 peered through the misty monsoon rains from underneath ponchos and anything else that might help them find a little comfort in the muddy trench. Assigned to the communications section of H&S Company, I was catching more than my share of perimeter duty. Since I was the cherry of the outfit that was nothing unusual in the Nam but it sure as hell had little to do with repairing radios which was my MOS or military occupational specialty. After scanning the dark perimeter I sloshed a couple of steps along the trench and entered a bagged and roofed bunker where I had unloaded the PRC-25 radio pack at midnight. A couple of waterlogged grunts or infantrymen from security platoon were wrapped in their ponchos and setting on ammo crates trying to stay dry and avoid the chill of the monsoon season. I felt no pity for them, I was cold and soaked too.

“How come you guys aren’t in position?”

“Aw hell, give us a break corporal, there ain’t nothing out there but maybe a rock ape or two,” one of them said, “you ain’t been here long enough to know.”

“I been here long enough to know that if you two don’t get back to your positions you’ll find out that you're not as short as you think you are.”

If it’s anything most marines try to avoid it’s having to stay in Vietnam past their rotation date on a legal hold because of some personal screw up. So both grunts reluctantly picked up their gear and went back down the bunker line to their positions.

I knew I had a lot to learn and I hated to push seasoned grunts but I had to make a situation report and how the hell could I do that with two posts vacant.

I picked up the radio handset, keyed it, and quietly said, “Yankee one, yankee 3, sit-rep all secure, over.”

“Three, one, roger, out,” came the reply.

Back outside the bunker under the constant rain I resumed my watch and tried to shelter my M-16 rifle as much as possible. Rifles could be tricky enough about jamming even when in good condition but so far I had not had any trouble with mine. It appeared that the government had finally gotten the problem fixed after lots of young men had died and were found with a jammed rifle in their hands. Even then there was no hurry it seemed, just another poor dumb son of a bitch dying for his country as General Patton so eloquently once put it.

As the descending flare was about to hit the ground and die I reached into my cargo pocket, removed another one and slammed the base of it with the heel of my hand. A whooshing sound traveled skyward followed by the loud pop of the illumination chute and again the barren kill zone beyond the concertina wire lit up. Scanning the kill zone for movement, I wondered what was really going on in Vietnam. What I was seeing was not jiving with what I had heard.

Ducking down in the trench, I lit a cigarette, cupped my hand around the glowing ash, and smoked. My watch told me that soon my shift would be over and I could make chow before hitting the rack. The patrol should be on its way back by now according to the checkpoints that I heard over the radio. Looking in the direction from which I knew they would come, I could see the wooden poles used to open the wire and the glowing eyes of the sentry dog staked out there, but not much else. Suddenly, about 200 meters in that same direction I heard the ack-ack-ack and saw the green tracers of enemy AK-47 fire immediately followed by the rapid burst and red tracers of several M-16s returning fire. The booms of the 12 gauge double ought bush gun could also be heard from the return fire. From the listening posts the radio net came alive with contact reports and as soon as I could log in I, now with the radio on my back, rushed down the bunker line and passed the word to the grunts who were already standing by. After another burst of M-16 fire mixed with M-79 grenade launcher explosions there was a lull in the action. Everyone on the radio net was instructed to remain in place and wait for further word.

As the siren atop the COC or Commanding Officer’s Communication bunker in the rear sounded the trench line began to fill up with marines. In the distance I could hear the funny sounding alarm of the ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam) 155 Howitzers and knew that they too were bee hiving and lowering the big guns. The once dark sky was now full of the sound and illumination of what seemed like a hundred pop flares going off as we all waited, staring out at that cleared ground beyond the wire.

Shortly, a helicopter gun ship showed up and mini gunned the area with a curtain of lead that looked like one big red screen descending to the ground from the dark sky above the flares. We called them spooky gunships and they could put a round into every square foot of a football field sized area in less than 30 seconds. Nothing above ground could withstand such withering fire. An eerie quietness took hold, broken only by the zipping sound of the spooky mini guns as the terrain was raked with lead. Earthbound marines looked skyward as if it were Zeus or some other God practicing his art from above.

When the chopper ceased fire and left, dawn broke so quickly it was almost like waking up from a dream. Colonel Blevins, the battalion CO, was now on the line and I could hear his operator, another com section marine named Tim, relaying orders for the patrol to break cover, reconnoiter for killed and wounded, and come in.

Usually no higher than a sergeant led patrols but it was Lt. Stansworth, the security platoon CO, leading this time and apparently he had been wounded by the first volley of AK fire. Word was that it was only superficial, having grazed his shoulder. Stansworth, a former force recon marine, was about as gung ho as they came and it was typical that he would be in the front during a firefight. That little action would later get him his captain’s bars.

After a bit the patrol radioed that they had two confirmed kills and were bringing them in. All eyes were on the gate in the wire when the patrol appeared, half carrying, half dragging two body laden ponchos. The Colonel left the trench and met Lt. Stansworth just in front of my position near a little bridge over the trench where they dropped the bodies. A small crowd began to gather, mostly officers but a few enlisted as well. They were snapping pictures as Tim and I stood off to the side and eyed the lumpy ponchos.

After rolling up the bloody sleeve of the L T’s jungle blouse and examining the dressing Col. Blevins asked to see the bodies.

The larger one was opened first, exposing a young Vietnamese male dressed in khaki shorts, a black long sleeve shirt, and sandals made from rubber tires. It was hard to recognize any features of the face which were now just a pair of cloudy dark eyes set in a ripped and bloody mass. It looked as if the double ought had done a thorough job clear through. From the open back of the skull there were parts of reddish grey matter spread on the poncho. Only a dark hole existed where an ear had been cleanly severed. The rest of the body was not in much better shape as evidenced by pools of half clotted blood that were starting to darken the mud around the edges of the poncho. But for the clothes, what lay there could have been the half finished job of a butcher suddenly called away from the back of his shop. Except for the occasional whirring sound of a camera advancing film it was utterly quiet as the Colonel pointed to the other smaller body and nodded for it to be exposed.

A large conical hat covered the head with the rest of the body in remarkably better shape than the first. Dressed in black silk pants and shirt and wearing the same kind of sandals, known as Ho Chi Minhs, it appeared from the large patch of blood on the shirt that this Vietnamese had been hit only in the upper torso. When the Colonel reached down and lifted the hat covering the head, a long stream of silky black hair that was caught in the chin strap cascaded down to frame the face of a lovely Vietnamese girl of perhaps sixteen. Her eyes were closed and except for the bloody shirt she might have been asleep. Everyone, including the Colonel, stared in open amazement. Not a camera shutter was launched nor a word said. A scene which no mere camera could capture lay before us and it was something that only we who experienced it could realize. Something that was and forever would be present to us youngsters of war standing there in shock. Always present in its absence, for it was our girlfriend, our sister or our buddy’s sister, the dream girl we wanted to go home to, or the one we hoped to find when we got there. It was a piece of us that lay there dead. Without another word the Colonel quickly placed the hat back over the girl's face and left. There was no weapon found.

Those first weeks in Vietnam saw me trying to carry out the duty that had been placed before me but as far as technical radio repair was concerned there was not much that I could do. We had neither the parts nor the equipment necessary to perform such operations. If we couldn’t cannibalize from radio to radio we simply shipped it up to the regiment for repair. Because of that techs like me usually ended up working down into the radio operator, or wire stringer jobs.

From Sgt. down rank was not a big deal in the com section which ran the COC bunker, the hub for all communications coming in or out of the battalion, and also monitored the nets of some nearby units.

The 1st, along with a few other units, was responsible for protecting the approaches to the Da Nang airstrip throughout that area immediately south of Hill 821. It was a large area that began at the east end of a valley that ran many kilometers into the countryside between lush green mountains. A pretty land dotted with rice paddies and small villages, crisscrossed by meandering streams. To stand atop one of those mountains under a sunny tropical sky and look out over that broad expanse of beauty one would think it one of the most peaceful places on earth. But from that same spot in the dead of night one would see red and yellow explosions along with the red and green tracers of small arms fire decorating the sky in many spots that had appeared so pretty and peaceful during the day. It was said that the Viet Cong owned the night. It was then that they showed just how jealous they were of their property.

All these things I was beginning to acknowledge. Things that one had to see to understand since they previously had not been fairly described by the drum beaters back in America. I was able to see that the gung ho marine and unit cohesion usually held up as an example in the states was almost non existent there in Vietnam. Nobody was unhappy when someone’s rotation date came, for to get out of there was the big prize, though the melancholy of being left behind was hard to avoid too.

When I first got there I tried to get along with everybody and quickly got to know several of the young men in my section. But probably more because I had grown up that way than because of the different timelines everybody was on, I didn’t get very close to many. Also, as I would later learn, getting close to someone complicated the dismissiveness necessary to keep the hurt and shame at bay when people died or the fear got too big. But just the situation we found ourselves in, fighting a war that was unnecessary and much too one sided, seemed to provide enough glue to hold us together to some extent.

Since I was a quick corporal I had the privilege of sharing half a hooch, a plywood structure with a GI tin roof, with two other corporals, Amos Rooter and Charlie Roderno. Charlie had come in country only a couple of weeks after me but Rooter was already half way through his tour. The other half of the hooch was partitioned off for the two sergeants in the section, Bob Winsonsky and Alan Blume. Because of that and our shared NCO status I got to know these individuals a little better than the others of lesser rank who all shared one large hooch.

One commodity that was never in short supply unless you were in the field was beer. Every evening after chow the club would open and it was there at the crowded tables that most social activity took place over countless beers served by pretty Vietnamese girls wearing ao dais. An ao dais was a beautiful combination of a dress split up the sides worn over long silk pants. The beer was paid for with MPC or military payment currency which was as good as real money and even preferred to the national currency which was the piastre.

When it came to the military culture there were quite a few more divisions than one would find stateside. Racial divisions in the war zone were more pronounced than in America because in Vietnam everybody had a gun. Vietnam was a white man’s war but the blacks, being easier to draft, got caught up in it disproportionately. Black soldiers took far more of the casualties than the whites, which along with the age old discriminatory practices of American racial prejudice caused considerable resentment and sometimes even rebellion. It was not unheard of to have actual firefights between the races although that was rare. But because in America it was usually only “the man” who had a gun and in the Nam everyone had a gun, suppression of the black race was far harder to accomplish. That led to a milieu where blacks and whites went their own ways absent the authority of the white cop with the only gun. However these segregated conditions did not exist in the bush where all were green and most interracial friendships were forged. But once back inside the wire the old standards and separations quickly reappeared, even among close friends.

Another divide could be found between those who used marijuana and those who didn’t. I had of course heard of pot and while in California had even known some marines who used it. I had tried it a couple of times before I went in the marines but didn’t experience any effects from it and considered it a waste of time when I could be drinking beer. Consequently I could always be found with the mostly white “juicers.” At least that was the way it was before Corporal Rooter turned me on.

Rooter, one of the corporals whom I had shared a hooch with, had been transferred to the marine air wing at Chu Lai but had literally dropped in aboard a chopper for a quick visit at the 1st while on some kind of temporary duty in the Da Nang area. As luck would have it or Rooter already knew, probably the latter, there happened to be a USO show at the club that evening. Almost always these shows would consist of a bare bones plywood stage and a Korean band with at least a couple of pretty girls in short skirts. They danced and sang American songs for the beer drinking, hooting jar heads gathered there. Laughter, macho jokes and too much to drink were standard fare at these events so Rooter and I quickly squeezed into the little club for some fun and beer.

After the show we returned to the hooch and were rapping about life down in Chu Lai when Rooter suddenly asked, “You want to get high?”

“What do you mean,” I replied, “we just drank all that beer?”

Rooter smiled and rolled his eyes.

“Yeah, but that was beer, I got some really fine Chu Lai weed. You ever try any weed?”

“Yeah I tried it a couple of times, it doesn’t do anything for me, can’t see what all the hoopla is about.”

Rooter eyed me skeptically.

“Yeah, where did you ever smoke any pot?”

“Back in the world, West Virginia,” I said. I was about to elaborate but Rooter burst out laughing before I could go on..

“West Virginia! You mean you never smoked any Nam weed? You really are a cherry. Come on let's go outside and smoke a couple of joints. Then you can tell me it doesn’t do anything for you.”

“Are you crazy,” I said, “you mean you’re packing around marijuana?”

“Hey take it easy, you’d be surprised at the number of heads around here. It’s cool. Come on new guy, I’m going to show you what’s happening.”

Once outside the hooch behind some refrigeration units Rooter pulled up the bloused leg of his jungle trousers and pulled a little cellophane package of pre-rolled joints out of his sock and fired one up. After inhaling deeply and holding the smoke in he passed the joint to me and exhaled.

“Take a big drag and hold it in.”

I did as instructed and as I drew on the joint the pot seeds compacted in it would sometimes explode in a small shower of sparks that for a split second would light up the darkness around us. Back and forth we passed the joint until it was too short to smoke and Rooter ate it. Neither of us said anything for a while. We just sat on the ground looking at the sky.

Rooter finally asked, “Man, how you doing, good weed huh?”

“I don’t feel a thing. Just a little bloated from the beer.”

“You're shitting me,” Rooter exclaimed as he went back into his sock, produced another joint, lit it, and passed it directly to me. I took the joint and after a long drag offered it back to Rooter.

“Hell no, not for me. I’m totally wasted,” he said, “wow, man, not getting off…..you smoke that one by yourself.”

“OK, but this shit don’t affect me, I tell you.”

We sat there for several minutes, Rooter quietly looking around at the night as I puffed on the joint, holding it in and then exhaling. When I had smoked about half of it a sudden rush overtook me. Nothing like the change overtime brought on by alcohol. This was like one moment the world was one way and the next it was different in the extreme. Suddenly I felt incapacitated and no matter how hard I tried I remained that way. Time took on aspects that were foreign to me and I lost track of how long we had been there but it must have been some while for when I looked down I saw the half smoked joint dead in my hand. I looked over at Rooter who was staring at me with a big shit eating grin on his face. Reaching the joint toward him and in the most serious voice I said, “You can have this back now.”

“Did you get your ass kicked, cherry,” Rooter laughingly said, “still don’t affect you, huh?”

I now definitely knew better than that.

“Lord have mercy, I am smashed. What the hell am I going to do. I can’t hardly move.”

Laughing, Rooter stood up, reached down, and grabbed me by the upper arm to help me stand.

“Come on, let's get back inside the hooch, you look like you're ready for the rack.”

After Rooter got me to my rack he left, never to be seen again, just off into the night or back to Chu Lai or some other unit. He wasn’t even carrying a weapon. Just that ass kicking Chu Lai weed like some vagabond who had quit the war and was now just touring the places he had been.

I laid there half on and half off the rack, almost blinded by the brightness of the overhead bare bulb. I felt as if I had been planted there and could only with time grow out of it. It still must have been early because I could hear some coming and going around me so I tried to act like I was just relaxing. It seemed so long ago that I was outside with Rooter but every indication was that it had only been a few minutes.

One thing was for sure, I was not immune to pot and for the first time in my life I was stoned. Fully dressed with not even my boots off, I was held up by the rack, and felt like I was made of stone. No longer would I consider such a feeling ridiculous. The section chief, a very tall thin black Ssgt. walked in, took one look at me peering up through the glare of the overhead light and knowingly smiled. Slowly shaking his head and wagging his pointing finger, he knew I was stoned. And I knew that he knew but not a word was said, then or afterward. The chief just quietly turned around and left. He was to rotate out soon and that was enough to keep him quite no doubt. Besides, we had known each other before he had made staff and became the section chief. Although I didn’t know for sure, I figured that he had had a few puffs himself over the past year.

In the beginning I didn’t smoke often but when I did I was amazed at the number of guys I knew who also smoked. The next time I decided to indulge I and Charlie Roderno, my remaining hooch mate after the transfer of Rooter, ended up in a remote ditch between the club and the wire. It was completely dark but the ditch was full of people and when the matches and Zippos were struck to keep the joints going I recognized half the com section. I also found out why not many blacks came to the club. Most of them were out in the ditch doing pot instead.

I didn’t do the communal pot thing much after that. Most of the time I only smoked with guys from my own section and to my knowledge, just as with beer, it never happened outside the wire. Usually I and another section member would sit out late at night, share a joint, and talk about the war and what we were going to do when we got out of it, Spending an hour just rapping and watching the pop flares shoot up into the sky and slowly drop back to earth, we felt removed for a little while.

Christmas and New Years Eve I was hidden away in the night watching the tracers fill the sky as marines all around hill 821 turned their guns to the air. These little gigs were a slim hold on the world across the sea. It all evaporated quickly once Christmas and New Years had come and gone but when my mother sent me a small box of cheeses for the holidays that little box went a long way as it was shared a little at a time among the section. That Christmas of 1968 and many of those that followed would always be associated with that gaily packaged box of cheeses resting under a hanging M-16 rifle and a couple of Christmas cards. I took a picture of it for my personal Christmas card that I eventually gave to my step kids many years later. That was before they and their mother left me, not having been with me even a year.

There are places and times in people’s lives that seem to take on a significance that one looking on might find odd. But for me, as meager and poor as it was in a war zone, that Christmas of 1968, along with the yuletide cheeses, became the last Christmas with any meaning. At that point in my tour I was still struggling to get along and remain a part of the World which I considered to be the USA. But my grip was not as tight as it had once been. Now instead of an angel atop my Xmas centerpiece there was a gun. Things had changed.

Time inside the wire was slow and that meant time to try and fill the empty feelings that nagged. But when I stepped beyond the concertina I was as full up of bone and blood as I could stand. The 1st had people a few clicks out into the bush every night on patrols and listening posts. And then there was the observation post beyond that. I had been on them all, humping the radio because the grunts had a hard time keeping anyone who could operate the radio, change batteries, and keep track of the different callsigns and frequencies. Long hours spent in the COC bunker assured that a marine from com section was up on all that stuff.

LPs or listening posts were the worst. Three guys with rifles, grenade launcher, starlight scope, and a radio were sent a couple of hundred meters out and a little ways up hill 821. They would find a spot, settle in and try to see what was going on, reporting every hour on the situation. No digging in or any of that defensive stuff. Just quietly hunkering down and trying to freeze in place for hours on end. The joke was that you listened until you heard them coming, reported it, and hoped they passed you by without knowing it. However it rarely worked out that way. In reality a listening post was fodder, no more, no less, and if you were unlucky enough to be there when Victor Charlie came you were unlikely to survive any fight from such an exposed position. But it would eliminate the element of surprise. Everybody hated listening posts and knew that it was a throwaway job with a posthumous purple heart as its only reward. Once when I thought I heard someone creeping through the bush my heart pounded so loud that I had to listen between heart beats. Peering in the direction of the sound for a couple of minutes I discovered it was just an insect moving among the weeds a few feet from my ear.

There were definitely other people out there in that darkness. Other LPs and at least one patrol. The fuzzy green mess seen through a starlight scope was almost useless at being able to define which was which. Back in the COC bunker the watch commander had a map and was supposed to keep track of everyone’s position. I knew that was not really effective because I had been humping on some patrols where the grunt sergeant in charge would tell us to just lay down and sleep. Consequently our location was not accurate..

I had almost killed some of my own men when I was on net control in the COC bunker because of that kind of bull shit. One of the LPs was reporting movement at a place where there was not supposed to be anyone. With the watch commander asleep in another section of the bunker, and not wanting to wake him, I took it upon myself to order grenades launched. Soon as I heard the explosions the screaming on the radio began.

“Stop that Goddamned shit right now!!”

Nobody was wounded but when they came in at dawn I was outside the COC bunker watching them pass. Although nothing was said, some very hard looks were exchanged. The watch commander never even knew it happened or if he did it was never mentioned. Just another example of some dumb son of a bitch dying for his country….. almost.

The 1st must have gotten some intelligence that indicated a threat to the observation post which was about 6 kilometers out. It was decided to pull an ambush on the far side of the hill that it occupied. Security platoon sent word that they needed a radio operator for the ambush but most of the lower ranks of the com section were already manning various radio posts and that left only a few NCOs and an officer. Officers, even within grunt units, never packed the radio so I, being the junior NCO, volunteered when the others firmly declined. A lieutenant that I had never seen was leading the ambush and that in itself was unusual. Plus a scout dog and handler were also going. Who was ambushing who, and why was a scout dog going on an ambush? I just chalked it up to Vietnam, the major American debacle where nothing seemed right. Altogether there were only eight of us who gathered at motor-t to board the truck that would take us out. The LT, me, and a corpsman plus five grunts, an M60 machine gunner, grenade launcher, dog handler, claymore man, and a rifleman. When we got on the truck one young black grunt was bitterly complaining, almost to the point of tears. He had only 9 days left on his tour and thought that it wasn’t fair to send him out when he was so short. He got no sympathy as the others ignored him and accepted the assignment as just another task to get through the best way they could. There was no joking around or any conversation as the LT rode in the cab and the rest of us rode in the back out the dirt road to the OP track. Black striped faces were serious, and except for the gear and black grease, we could have been a bunch of strangers sitting in a waiting room to see our doctor back in the world. Once we got to the little track leading up to the OP the truck dumped us and returned to base.

As the sun was setting and a tropical bluish green dusk was fast coloring our world we humped up the track to the OP and gathered around a burn barrel to receive our final briefing.. Suddenly a loud metallic sound interrupted the briefing. It took but an instant for us to see the live M79 grenade bouncing on the ground by the burn barrel. We scattered in all directions. The dumb shit carrying the grenade launcher had accidentally discharged his weapon but since the round traveled less than six feet before slamming into the barrel the safety mechanism had kept it from exploding. When we realized that everyone calmed down and the LT told us what we should have already known.

“Don’t load your weapons until we leave the perimeter.”

Not even an ass chewing for stupidity took place, probably because it wouldn’t have made any difference. Plus there could be much more stuff to come very shortly. Why put down one of the few men you had to fight it with? Nam was different from the gung ho bull shit back in the states. People actually got killed ...and not always by enemy fire.

The LT made sure that my radio worked, the claymores were ready to deploy, and that there was sufficient ammunition before leading us through the wire. Once outside he told us to lock and load our weapons. The handler and his dog walked point, stringing us out a little. The LT and I were in the middle going down the rocky foot trail toward the valley floor. It was almost completely dark but the monsoon season had passed so we had the stars and a small moon to see by.

I had never been off the road in that territory and didn’t know the terrain so I just followed the LT and hoped that he had read the map correctly. On a day trip out to the OP I had seen Vietnamese carrying loads on shoulder sticks so I knew there were people around there. But now the road was long gone. We wound around and up and down small hills, putting considerable distance between ourselves and the OP. The terrain was not bad and with the extra adrenaline the pace seemed easy but visibility was not good as we passed through tropical bush with no clear vision of anything but the person ahead. It was no wonder that we saw no sign of any human presence.

The narrow path resembled some sort of game trail that meandered through the undergrowth. Only the tops of palm trees could be seen, dark shapes outlined against the night sky. Eventually we left the trail and cut across a wide grassy corridor, the first place that I could see ahead to the the dog handler and the front of the patrol. The dog was obscured by the grass but in the faint light there was everyone else, strung out across the thigh high tropical meadow. Word was passed back to hold up because the dog had alerted on something. Everybody froze while the handler checked it out. I wondered what in the world could there be to check out in that darkness. The dog had alerted, something was wrong. How could one know anymore than that. I was not used to the scout dogs because they usually came in and went out on helicopters--far out, all over the Nam to the grunt units who lived in the bush. We were flanked by a small bushy hill on one side and a stretch of palm trees with the same dense undergrowth that we had just come through on the other. Realizing that we were very exposed I went from being anxious to just plain scared. When I returned my attention to the point I saw the muzzle flashes and heard the AK-47 fire coming from beneath the palms to the front. Almost simultaneously another series of flashes and sound came from the same tree line nearby. I dropped to the earth as the LT screamed to return fire. Hugging the earth but still managing to get my rifle raised I emptied my magazine in the direction of the tree line as the others laid down what fire power they had. Three magazines I went through in a couple of minutes, blindly, by rote, not thinking or wishing for anything but to please not die. I lived only within the all encompassing sound of the fire. Desperately trying to get more ammo from the bandoliers tangled around my chest, I began to discriminate the sounds of grenades from the launcher as they hit along the tree line. I thanked God for that dumb son of a bitch that almost blew us all up back at the burn barrel. Not to mention the M60 machine gunner I could hear firing furiously.

I couldn’t really see what was going on because I was so scared that I couldn’t raise my head out of the grass far enough to see much of anything. It must have been a full two minutes of withering fire before I heard the LT yelling to hold the fire. Still glued to the earth when the LT appeared beside me and told me to contact the battalion or the OP, I reluctantly sat part way up and flicked up the tape antenna on my radio. The LT ran off toward the point. I tried to make contact but got nothing, not even the sound of a squelch. I checked the antenna connection but that did no good either. That left only the battery so I rolled over and shrugged off the radio with the bandoliers of ammunition tangled around it. Always I went out with a new battery and logged in but this one must have been bad so I started un-taping the spare I always carried at the bottom of the pack. That’s when I felt it, a neat round hole in one side of the radio and a large jagged exit hole out the other side. The thing was useless, leaving us with no communications. The LT returned and said that the handler had been hit bad and wanted to know if I could get a med-evac. All I could do was show the bullet holes in the useless radio and mutter a few words. I was so scared and ashamed that I could hardly talk.

Amazingly there were only two wounded, probably because the attack had been a classic hit and run. The machine gunner had been hit in the lower left arm, a clean flesh wound with minimal damage. A field dressing would temporarily take care of it but the handler had a sucking chest wound and was barely conscious. The corpsman worked on him for what seemed like a long time, almost losing him a couple of times, trying to get him stabilized enough for carrying. He gave long odds on his survival if he wasn’t lifted out but the best that we could do was carry him back to the OP and call for a dust off there.

Nobody, including the LT, wanted to reconnoiter the tree line. If there were any VC bodies there they could stay there. Besides there were most likely booby traps as well. Somehow we had walked right into the ambush either by making too much noise in our approach or someone on the inside had passed the word about the operation. I wandered about all the drunk marines and pretty girls at the club but what the hell did I know, I just wanted to get the hell out of there. It took the rest of the night but we tied some ponchos together and took turns carrying the handler as his confused German Shepherd remained with whoever walked point. During my turn to help with the carry I listened to the awful wheezing and moans as the handler tried to breath. Many times we had to stop and let the corpsman work on him. I was glad to get away from that wheezing sound when I was relieved but the next time it was my turn I heard nothing. Knowing that the handler must be dead, I quietly cried and cursed God.

Near the OP we popped a red smoke grenade in the misty dawn light and yelled out who we were. Once inside, I got the coordinates and called in a med-evac with the OP radio.

As the chopper touched down another corpsman quickly jumped out and examined the handler lying there on the bloody ponchos. White that showed through his half closed eyes and lips that looked like they had been painted blue on his pale young face formed the vision that would always represent that mission for me. The exposed chest was still and covered with a mixture of dried mucus and blood. What had once been alive and loved by someone was now surely long gone.

Out in the valley, on a patchwork of different shades of green, the sun was starting to reflect from the numerous paddies and except for the noise and dust from the chopper it was so maddeningly serene that I wanted to scream.

Quickly and with the detachment of repetition the corpsman looked up at the LT and shook his head. The corpsman and a couple of grunts lifted the handler into a large dark plastic bag laid out on a stretcher and zipped it up. Now handling only cargo, the corpsman and crew chief raised the stretcher, shoved it through the open door of the chopper, and hopped aboard as it lifted off. The whole dust off had taken less than three minutes and I figured that was how long it took to get out of the war that way. So fast that I didn’t even know the handler’s name.

After the failed ambush I began to slide even more, smoking more pot, drinking more, and giving less of a damn about fighting the communist. What the hell was I doing there anyway. I had known from the beginning that it was messed up but I had thought that if I applied himself I could stomach it and move on. I watched the higher ups for a clue as to what this war was really about. It took very little time for me to become convinced that they had no idea either…other than to advance their own careers. From this conviction I developed a hatred of authority and class that would plague me from then on. Those in authority would throw my life away to gain an advantage in their quest for a bigger, better, and richer American dream. I may have come from poor stock and little family but Vietnam was showing me that there were some things that I could not stomach. Unforgivable things. That kind of unholy sacrifice for gain, dressed in the garments of patriotism, be it personal or national, was one of them.

I was not alone in those views. All through the war zone similar attitudes were developing. However I continued to follow orders whereas some others often refused and ended up in the brig. Many times for murder.

In a neighboring unit one staff NCO was so hated by his men that they faked an enemy attack then cut him down with a machine gun as he ran out his door to hide in a nearby bunker. Many of the murders, called “fragings,” after the fragmentation grenade, were done with hand grenades thrown on or under sleeping victims. Or simply by shooting them during a firefight or enemy attack. It was a terrible thing to do but it all started with the lies and the draft, then developed into a festering boil that eventually, in some cases, could not be contained. The majority of those murders were never prosecuted. And that along with a similar rebellion in the US helped end America’s involvement in Vietnam. But for the young people caught up in it at the time the damage was done. I was one of them. Despite my own feelings about the war, I had tried to comply with the bull shit. Now I only wanted out and away from those who willingly participated in it, lived by it. If I couldn’t get away physically I would do so mentally just as I had done with mind travel in boot camp on Parris Island. But the war was much bigger than boot camp and I found it impossible to get away. Even with the use of drugs and alcohol there was always the next time. The next useless bull shit to put up with, the next wasting of a human being. No longer did I care about who won the so-called fight for freedom. We were all losers as far as I was concerned. The young people like me had a favorite phrase among ourselves that grew out of that desperate loss.

“Fuck it, it don’t mean nothing.”

There was no event or disappointment, including death, that could not be somewhat assuaged with the utterance of that phrase.

An order came down to the 1st to send a com marine of lower rank TAD or temporary assigned duty to Yokosuka, Japan for seven days. I got the nod and was told to report to the marine barracks at the big naval base and attend a class on some antiquated piece of communications gear. It was just another ridiculous quota that had to be filled. Since I was becoming the old man in grade as a corporal, the new section chief, a Mexican who had made the marines his career, decided I should go. Perhaps also figuring in the mix was that I, despite my attitude, was known to have a bit of intelligence. That would make me a good stand in for the 1st when it came to the technical stuff. As far as I was concerned I couldn’t believe my luck. I welcomed the chance to get out of Vietnam for a week.

I arrived at the little operations center at the air strip and presented my orders. After waiting a while, I was told to grab my gear and board a jeep just out the door. I rode out onto the tarmac to an area where a big Air Force cargo jet was being loaded with aluminum crates.. Hopping out of the jeep, I went to the little side door under the wing and offered my orders to an Air Force Tech Sergeant standing by the pull down steps. The Sgt. glanced down at the orders and looked up at me.

“You going to Japan?”

“I guess I am,” I replied.

Having already turned his mind to something else, like what kind of chow he would get for lunch, the Sgt. simply jerked his thumb up and said, “Get aboard.”

Inside the hold of the huge plane there were large wheeled metal slabs mounted on tracks that ran along the deck from the front to the back. They were used to slide the cargo on and off. A couple of small fold down benches made out of nylon straps and aluminum tubing were hung on each side of the bare bulkheads for any passengers and that was it. No windows, only the back doors and ramp large enough to drive armor or semi trucks on.

As another young marine showed up for the flight the load masters continued to shove stacks of aluminum crates aboard until we were full up with cargo. The doors closed and we took off.

The hold was dimly lit by a couple of small red bulkhead lights and it was quite cold. After coming out of the tropics and flying for about an hour, I felt like I was freezing my ass off. The crew remained forward in the sectioned off nose of the plane while the other marine and I rolled down our sleeves, propped our feet on the cargo and hugged ourselves to stay warm. We hoped that the flight would be quick. It was not. The other marine got up and started walking back and forth in the space between the cargo and the bulkhead, trying to stay warm. He eventually paused beside a tall stack of the aluminum crates and began fooling with one of the attached tags. He stood there for a long while and I wondered what could be so interesting about a cargo tag. Finally, returning to the strap bench with a look of astonishment on his face, he said, “Man, you know what all this cargo is?”

I shivered a little, “What ?”

“Man, these are bodies, KIAs, we’re on a morgue shipment of American dead from graves registration.”

Suddenly we both knew why it was so cold. I slowly removed my boots from the body in front of me and wondered if it was the dog handler I had helped carry out of the bush.

The constant whine of the jet engines filled the air as I studied the deck. Without looking up I said, “Fuck it, it don’t mean nothing.” The other marine just nodded and studied the deck as well. The two of us never spoke again until we parted upon landing at Yokota Air Force Base in Japan.

In my bush fatigues and floppy hat, wearing once black boots that were scuffed tan from use and not really giving a shit, I was put through a rigorous customs search. The young Air Force guard went through every single item that I carried and then searched my person as well before allowing me to move on. I received many a second look from the spit and polished military personnel coming and going at the busy air base but not one person messed with me. I did not bother to salute nor speak. Simply presenting my orders and silently going where directed I almost dared anyone to get in my space. Straight from the cargo of the dead, I didn’t care what anyone thought. What the hell could they do to me anyway, send me to Vietnam?

It was late at night as I rode a military bus for about two hours through one continuous stream of multicolored neon lights with Japanese writing in characters that were completely foreign to me. As the only passenger on the bus I passed through the outskirts of what I figured to be Tokyo. I followed the coastal congestion through Yokohama and further south to the big naval base at Yokosuka and its Marine Barracks. When I reported in the duty marine showed me to an isolated and unused part of the barracks where I unrolled a mattress, made a rack, locked my gear in a locker, and slept.

The next day, wearing the same attire and with the same attitude, I was sure that this strict marine unit would reprimand me. Marine Barracks, throughout the Corps, was known for its spit and polish, but the reprimand never happened. Sometimes I would be asked who I was. I would simply say that I was TAD from Vietnam. That was the end of it no matter where I went on the base. Not one person accosted me, though I looked like military rabble.

I found my class when it started and went to it when I was supposed to, sometimes falling asleep. But even that was ignored because, just as I had expected, it was a typical bull shit quota class on some old piece of gear that was no longer used. The lifer who had ordered it was so out of it he didn’t know that and anybody who did was not senior enough to tell him.

Everything I did, I did alone. I knew no one and wanted it to stay that way. Occasionally, at the almost vacant NCO club, some sailor would initiate a conversation from the next bar stool just long enough to find out where I was from. Having found out, they would silently smile for a moment and politely excuse themselves. There was no problem with that, in fact I welcomed it, for deep down I knew it didn’t mean nothing anyway.

Passing through the week of class and learning nothing was a skate since the classes didn’t last a full day. I had time to visit the Great Buddha down in Kyoto and take a train ride to Tokyo. Once I had a steam bath and massage followed by a visit to a little bar in downtown Yokosuka. The owner, a beautiful madam, tried to saddle me with a young beginning prostitute. After drinking a lot and buying the young girl drinks which I knew were only tea I went to a hotel by myself. Prostitutes were no use to me and never had been. Not because I was otherwise adequately serviced, but because they just didn’t do anything for me.

Those things I did in a couple of days. Mostly I just wandered around, whether on base or off, watching the people and always figuring that they had no idea of the things that existed beyond their bubbles of concern. To them it didn’t mean nothing either. Why should it mean anything to me? But always in my mind I knew that I didn’t have long to sit on the fringe of real life and speculate as I watched it come and go. For the poor white trash of Appalachia it would be back to the Nam where such stuff was ridiculous and never rested well on the conscious to begin with.

The week in Japan went by so quickly that later it became like a dream that couldn’t be remembered two minutes after waking.

After reversing my mode of travel used to get there, minus the crated war dead, I found himself back in Vietnam not sure that I had ever been gone. Nothing had changed. Only it was hotter and drier as the summer approached.

During this time when forced into competition with other marines for advancement I always did well by just simply regurgitating the material that had been fed to me. My attitude never changed but when the facts of the data were posted I found myself at the top of the list, an irony lost neither on myself nor the lifers. The CO of the 1st must have thought that it was a big deal though for it wasn’t long until I was given a plaque proclaiming me to be the marine of the month. Somewhat amused with all the hoopla and the trinkets being passed around, I wondered why this corporal with so much time in grade was getting all this candy. Had they forgotten that I had been turned down for Sergeant once already because I wouldn’t lie and say that I intended to make a career of the crotch. In fact I had been so emphatic in my rejection of that idea that the much surprised lifer on the board who asked the question had to ask it again. When I answered with the same emphatic, “No!”, the lifer, with an angry look on his face, told me that I could go.

I was probably the senior corporal in the whole company but after the marine of the month thing it wasn’t long until I was informed that I made sergeant and would receive my warrant at a company ceremony the following day.

The next morning the com section LT, an ex-school teacher from Boston, formed us up and made sure I was presentable. The company commander, an older grey haired captain who was a mustang, which is an officer that has risen through the lower ranks, came out of the company hooch, said a few words and then ask me to step forward. The old captain walked up close and squarely faced me.

“Corporal Hayes, you have earned this promotion and I am pleased to give it to you. I know that you will not stay in the Marine Corps but I hope that you will use this promotion to inspire you in your civilian life to achieve success wherever you can. Congratulations.”

I replied, “Thank you, sir,” as I accepted the warrant, shook hands and saluted.

Looking a little tired and somewhat sad the captain then told the company 1st Sergeant to dismiss us and went back into the hooch. It was done and I, while I treated the whole thing respectfully, knew that the only reason that I had gotten promoted was because it would have been an embarrassment for me to remain a corporal. The old captain was not, nor had he ever been, part of my problem. Because he was old and near the bottom of the back side he could be trusted to not try and gung ho his way to greater things at another’s expense. Just like me, he was simply trying to get through Vietnam and back to the world. I saw it written on his face and heard it in his words and for that I am thankful. Other than that the whole thing meant nothing nor, more importantly, did it change anything.

I moved my gear into the best part of the hooch with Winsonsky, known simply as Wins, the only other buck sergeant in the section. Sgt. Blume, after shipping over for Staff Sergeant and ten thousand bucks, had rotated back to the states so I took his empty rack underneath Wins.

Wins was the wire chief. He taught me how to string wire and use a set of gaffs to get up the poles. I was stringing and troubleshooting com wire in addition to filling in the operator slots. The wire jobs took me out in order to keep the landline communications to other units in the valley working. It was work that was done only during the day and it was almost always uneventful.

Wins came from Idaho and, like me, was from the poorer class. We got along good. We wanted the hell out of the Corps and Nam and that shared passion was enough to make it easy to share the same half hooch. Roderno was now alone in the corporal’s quarters in the other half of the hooch so most of the time we just left the adjoining door open and shared the whole hooch.

Cpl. Charlie Roderno had come to the 1st a little later than me. He was a tech also but, like everybody else, cross trained in all the com section responsibilities. Younger and shorter than me and a bit on the heavy side, he pulled his weight just as well as the next guy. For someone so young in a combat zone Charlie had a calm demeanor and was slow to anger, a fact that would sometimes make him the butt of cruel jokes that ass hole marines liked to play. That and the fact that he had a wife and baby made Charlie seem a little different than the ordinary jarhead. Recently he had gone on emergency leave to attend his father’s funeral. He had died suddenly, yet through all that grief and responsibility Charlie had remained solid and kept an even keel. Or, perhaps because of those things, he saw a bigger picture than most and it steadied him.

With my aloofness, I matched well with Charlie and his steady temperament. Maybe that was why we tended to pull together. Whatever the reason, Charlie was the closest friend that I had. We often got high together as we let the crotch and the war go by, talking about other things like philosophy and why we thought things were the way they were. Rarely would we resort to the “it don’t mean nothin” equation. Mostly because Charlie wouldn’t allow it. He would challenge me on it in a way that left me vulnerable and made me look at myself. Because of this tendency to try to get to the root of things Charlie was not the average marine’s favorite kind of guy. Although in a different vein, his analytical interests put him almost as aloof as me. In a marine combat unit such qualities can be very hard to come by and to have one, let alone two complementing individuals of such nature was rare. For me, in a land of worthless endeavor and sham, along with a multitude of other undesirable qualities, my relationship with Charlie had value. And that made it important where no real importance seemed possible. As a result of that it turned out that even I grew a chink in my armor.

When the war was not heating up around Quang Nam Province life in the 1st got so boring that almost any excitement was welcome. It was also a good time to get into downtown Da Nang to the giant military PX and buy some hard liquor. Charlie and I hitched a convoy into the crowded city. We got off just on the far side of the local shanty town next to the PX and cut across the squalor of the makeshift village.

Betel nut chewing women, stirring a pot of who knows what, squatted in front of their shacks constructed of junked military material. The pungent smell of nuoc mam or fish sauce was so thick that it would turn your stomach if you weren’t used to it. Peasants, chased from their homes in the countryside, mostly by the US military, saw us with our M-16s coming. With betel nut blackened teeth, they smiled up as we walked by. After we passed they frowned at each other and spit long streams of black juice into the dust beside their fires. There were no men but there were plenty of kids, not even waist high, that crowded around us, begging and trying to reach into our pockets on one side while just as many tried to tug our watches off on the other side. Some of them reached up little packets of 10 marijuana joints for sale, $1.00 mpc. Other kids, in broken English, would hawk their sisters who were waiting among the shanties, hoping that their little pimps would bring some money home for rice. Most were starving. Once healthy people who had proudly owned and farmed their own land were relegated to lives of abject poverty, their land now part of an American free fire zone.

Charlie and I hurriedly got through this shameful result of the war and past the guarded gate into the PX. We bought a fifth of Jack Daniels and a couple of cartons of cigarettes. After looking around at all the cheap electronics and jewelry we made our way back out to the street and caught another convoy going back south. As we passed the road to the 1st and hill 821, we jumped off and caught a six by or large troop truck that took us back to the unit. We did pretty good, in and out and still had time for evening chow, which we skipped, knowing that the COC bunker would have plenty of night rations later if we got hungry. Instead we secluded ourselves in the hooch, cracked the Jack Daniels, and proceeded to get wasted, eventually crashing late in the evening.

In the morning I continued to sleep through the explosions and shaking hooch, Tim rushed in and roughly shook me awake.

“Hurry up and get your radio and flak jacket on, the ammo dump is going up.”

As the hooch continued to shake from the explosions I hurriedly got geared up while the prior night's Jack Daniels caused its own kinds of explosions in my head. So far the fire and explosions had not engulfed the 2000 pound bomb bunkers and the 1st was just trying to stand by and hope that it could be contained. I and Charlie, who was no doubt also hung over, were sent to the area closest to the ammo dump to secure the generator and make sure it kept working. We just sheltered against the sand bagged diesel machine, smoked a cigarette, shot the shit, and listened to its chugging while explosions rocked us. Hungover and just another day in Vietnam, neither of us were very concerned because we knew that there were worse things. After about an hour of increasingly heavy explosions we received word that the 2000 pounders were about to go up. We should get the hell out of there.