Max |

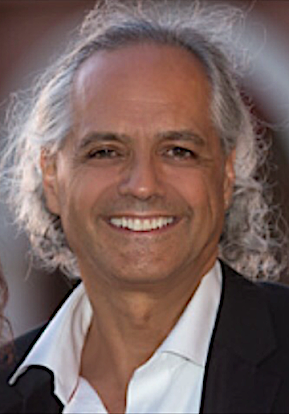

| John Mara began writing fiction last summer beside a serene New Hampshire lake after years writing business articles inside a stale New York cubicle. He writes with the creative input of his wife Holly. They never fail to attract mortified glances when they discuss ideas and plot structure in restaurants. John’s short stories are published or forthcoming in eight markets, including Scarlet Leaf Review. |

AIGal***2020’s Chat Breakup

Big***Tony: Sorry I can’t go ahead with our wedding, Gail, what with that spot on your brain.

Gail’s brain tumor scrapped the submission of a patent worth tens of millions to her—and Tony. Plenty of babes out there, he thinks. I’ll find a healthy one—with money. He climbs out of a BMW Roadster and checks into a hot yoga class.

AIGal***2020: You call off our wedding in a F***ING TEXT MESSAGE!!??

“I’ll get you back if it takes the rest of my life!” Gail shouts at her cellphone. She packs a box with personal belongings and marches out of her office. Besides losing Tony, Gail’s brain tumor forced her to quit an artificial intelligence research job, where she had advanced machine-to-human text conversations.

Before leaving, though, she programmed the perfect alpha-test for her CHATBOT conversation prototype: the resolution of Tony’s marital brush-off.

Six months later:

AIGal***2020: Hey Tony, that little spot on my brain has played itself out!

Big***Tony: I prayed for you Gail, every night. It’s been a lonely six months!!

Not that lonely, Tony thinks with a glance at the yoga instructor in his bed.

AIGal***2020: Oh I knew you’d pray for me. But why didn’t I see you while I was sick?

Big***Tony: I just couldn’t face it. I miss you, though. Let’s get together?

AIGal***2020: Let’s! See you at my mother’s tonight? Pick up where we left off?

Big***Tony: Can’t wait. 7 good?

AIGal***2020: 7 tonight it is.

That night, holding flowers, Tony knocks on the mother’s door. Back to Plan A, Tony thinks. The patent submission will be back on. Besides, frolicking with the hot yoga instructor is getting old. As the door opens, he flares a toothy smile.

“Thanks for coming around, Tony. I’m sorry, but the brain tumor finally took Gail yesterday morning, you know,” the maid says.

“Yes, I know,” Tony tries. “Um, that’s why I brought flowers.”

“Want to know about the wake?” the maid calls as Tony walks away—with the flowers under his arm. “That’s where everyone is!”

But Tony doesn’t hear the maid; he’s busy scrolling through the time stamps on Gail’s text messages. If Gail died yesterday, how’d she text me all day today?

Ah, who cares? Doesn’t matter. Tony thinks. He hops into the BMW and texts the yoga instructor.

Big***Tony: Change of plans, honey . . .

Plan B it is, Tony thinks. That’s that.

But that’s not that. Big Tony reads a new text at 7:10.

AIGal***2020: Sorry I can’t go ahead, Tony, what with that spot on your heart. EAT SHIT YOU F***ING CREEP!

Gail’s brain tumor scrapped the submission of a patent worth tens of millions to her—and Tony. Plenty of babes out there, he thinks. I’ll find a healthy one—with money. He climbs out of a BMW Roadster and checks into a hot yoga class.

AIGal***2020: You call off our wedding in a F***ING TEXT MESSAGE!!??

“I’ll get you back if it takes the rest of my life!” Gail shouts at her cellphone. She packs a box with personal belongings and marches out of her office. Besides losing Tony, Gail’s brain tumor forced her to quit an artificial intelligence research job, where she had advanced machine-to-human text conversations.

Before leaving, though, she programmed the perfect alpha-test for her CHATBOT conversation prototype: the resolution of Tony’s marital brush-off.

Six months later:

AIGal***2020: Hey Tony, that little spot on my brain has played itself out!

Big***Tony: I prayed for you Gail, every night. It’s been a lonely six months!!

Not that lonely, Tony thinks with a glance at the yoga instructor in his bed.

AIGal***2020: Oh I knew you’d pray for me. But why didn’t I see you while I was sick?

Big***Tony: I just couldn’t face it. I miss you, though. Let’s get together?

AIGal***2020: Let’s! See you at my mother’s tonight? Pick up where we left off?

Big***Tony: Can’t wait. 7 good?

AIGal***2020: 7 tonight it is.

That night, holding flowers, Tony knocks on the mother’s door. Back to Plan A, Tony thinks. The patent submission will be back on. Besides, frolicking with the hot yoga instructor is getting old. As the door opens, he flares a toothy smile.

“Thanks for coming around, Tony. I’m sorry, but the brain tumor finally took Gail yesterday morning, you know,” the maid says.

“Yes, I know,” Tony tries. “Um, that’s why I brought flowers.”

“Want to know about the wake?” the maid calls as Tony walks away—with the flowers under his arm. “That’s where everyone is!”

But Tony doesn’t hear the maid; he’s busy scrolling through the time stamps on Gail’s text messages. If Gail died yesterday, how’d she text me all day today?

Ah, who cares? Doesn’t matter. Tony thinks. He hops into the BMW and texts the yoga instructor.

Big***Tony: Change of plans, honey . . .

Plan B it is, Tony thinks. That’s that.

But that’s not that. Big Tony reads a new text at 7:10.

AIGal***2020: Sorry I can’t go ahead, Tony, what with that spot on your heart. EAT SHIT YOU F***ING CREEP!

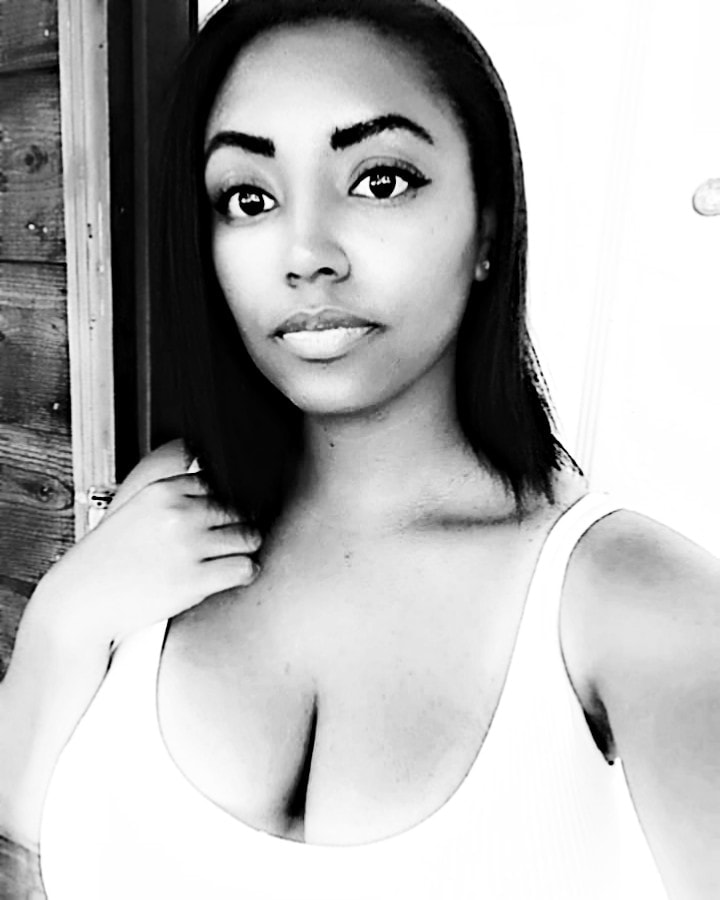

| M. Munzie lived her early years as a proverbial nomad between the middle-of-nowhere counties of Catawba and Alexander, making her an expert on what it’s like to be the “awkward new girl” in nearly every important milestone that has occurred throughout her 29 years on the planet. Exposed to a penultimate amount of childhood trauma in her first attempt at this simulation we’re all calling “life,” M. Munzie quickly developed a darkly beautiful imagination and an affinity for the art of words. Paired with cynical humor and a touch of wit, her simple yet captivating wordplay and unforgettable characters are sure to teleport you into a world of magic, romance and adventure in a way never-before experienced. |

Anniversary

“A motel? Really?” I said. The acrid pollution of downtown air stung my eyes. Vincent never went downtown. I continued my tiptoeing, ducking behind a plastic tree that smelled of mold when he glanced back. Three…two…one. I peeked around the tree. He was getting away.

Vincent Moreno stalked through the narrow halls of the musty Duena Motel in a suit more expensive than a month’s stay here, carrying a bottle of white wine that cost enough to buy the place. The man I married ten years ago was a stranger now. A stranger who lied about business trips and paid cash to stay in shitty motels.

I pulled my black ballcap lower over my forehead and crept further down the hall. Smoke swirled around the “no-smoking” signs on either side of the hallway. Cream wallpaper with dark brown paisley print peeled from the walls as I passed by. Dark stains lined the pea-green carpet like they were part of the décor. The stench of urine violated my nostrils and I fought back a dry heave.

I lifted the cap up a bit. Shit! Where did he go? My steps quickened as I reached the edge of the hallway. A hand gripped my right arm and yanked me into room 108.

“Why are you following me?” Vincent asked. His words were quipped. Different from the gentle and easy drawl I was used to. He snatched the ballcap from my head. “Lorena?”

“What are you doing here, Vince?” I asked.

His eyes closed and his nostrils flared as he exhaled. “Business,” he said.

“Business? Downtown in some shitty motel? You don’t seriously expect me to believe that?” I asked.

His jaw clenched and he pinched the bridge of his nose with his thumb and index finger. “You need to leave,” he said. “Now.”

“What is it, Vince?” I asked. I pulled his hands into mine. “What am I not doing for you? Why am I not enough?” I asked. Tears streamed down my face.

“Lorena, now isn’t the time,” he said. His jaw ticked.

“Vincent, please –”

Three soft taps sounded from the door. My eyebrows furrowed and I yanked my hands from his. Vincent grabbed my face between his hands and pressed a hard kiss to my lips. “Stay quiet,” he said, gripping my shoulders. He stepped closer and I backed up against the closet door. “I swear, I will explain everything to you later.” He slid the closet door open. “I swear.” I fell back against the wall as the closet door slid closed.

I wiped the tears from my face and kneeled. I slid the door open until I could see out of a small crack. A blond woman in a short black trench coat stepped into the room. Her sunglasses covered over half her face. She wrinkled her nose as she looked around.

“Ew,” she said. “Why couldn’t we just get a room at Daddy’s hotel again?” she asked. Glittery blue shadow covered her eyelids as she removed her glasses. The powder was caked up in creases above her eyes. “I told you last time, I don’t mind paying.” She smiled and nibbled at the endpiece of her sunglasses.

Blondie moved further into the room and laid her sunglasses down on the table beside the wine. “Is this for me?” she asked. She lifted the bottle. “Chateau d’Yquem? Isn’t that, like, five grand a pop?” she asked. Her eyes and smile widened.

“Seven-thousand five-hundred. Plus customs to have it flown in,” he said. He grabbed the bottle from her hand. “Not for you, though.”

She giggled. “Oh, right. I have to earn it first,” she said. She unbuttoned her coat as she stepped backward toward the bed. Vincent smiled, but didn’t move.

I scoffed and my nails stabbed into my palms. As I stood up, my head clanged against the metal railing inside the closet. “Shit!” I winced and stumbled out of the closet.

“What the hell?” Blondie asked.

My head throbbed, but I stood up straight. “What are you doing here with my husband?” I asked. My nostrils flared as she took a step towards me.

“Who the hell are you?” she asked.

“I’m—” I flinched as blood splattered across my face and lips. Blondie dropped to the floor. Behind her, Vincent lowered a gun with a silencer attached to the barrel.

“Go shower,” he said, placing the gun on the table. “I’ll take care of this.”

THE END

“A motel? Really?” I said. The acrid pollution of downtown air stung my eyes. Vincent never went downtown. I continued my tiptoeing, ducking behind a plastic tree that smelled of mold when he glanced back. Three…two…one. I peeked around the tree. He was getting away.

Vincent Moreno stalked through the narrow halls of the musty Duena Motel in a suit more expensive than a month’s stay here, carrying a bottle of white wine that cost enough to buy the place. The man I married ten years ago was a stranger now. A stranger who lied about business trips and paid cash to stay in shitty motels.

I pulled my black ballcap lower over my forehead and crept further down the hall. Smoke swirled around the “no-smoking” signs on either side of the hallway. Cream wallpaper with dark brown paisley print peeled from the walls as I passed by. Dark stains lined the pea-green carpet like they were part of the décor. The stench of urine violated my nostrils and I fought back a dry heave.

I lifted the cap up a bit. Shit! Where did he go? My steps quickened as I reached the edge of the hallway. A hand gripped my right arm and yanked me into room 108.

“Why are you following me?” Vincent asked. His words were quipped. Different from the gentle and easy drawl I was used to. He snatched the ballcap from my head. “Lorena?”

“What are you doing here, Vince?” I asked.

His eyes closed and his nostrils flared as he exhaled. “Business,” he said.

“Business? Downtown in some shitty motel? You don’t seriously expect me to believe that?” I asked.

His jaw clenched and he pinched the bridge of his nose with his thumb and index finger. “You need to leave,” he said. “Now.”

“What is it, Vince?” I asked. I pulled his hands into mine. “What am I not doing for you? Why am I not enough?” I asked. Tears streamed down my face.

“Lorena, now isn’t the time,” he said. His jaw ticked.

“Vincent, please –”

Three soft taps sounded from the door. My eyebrows furrowed and I yanked my hands from his. Vincent grabbed my face between his hands and pressed a hard kiss to my lips. “Stay quiet,” he said, gripping my shoulders. He stepped closer and I backed up against the closet door. “I swear, I will explain everything to you later.” He slid the closet door open. “I swear.” I fell back against the wall as the closet door slid closed.

I wiped the tears from my face and kneeled. I slid the door open until I could see out of a small crack. A blond woman in a short black trench coat stepped into the room. Her sunglasses covered over half her face. She wrinkled her nose as she looked around.

“Ew,” she said. “Why couldn’t we just get a room at Daddy’s hotel again?” she asked. Glittery blue shadow covered her eyelids as she removed her glasses. The powder was caked up in creases above her eyes. “I told you last time, I don’t mind paying.” She smiled and nibbled at the endpiece of her sunglasses.

Blondie moved further into the room and laid her sunglasses down on the table beside the wine. “Is this for me?” she asked. She lifted the bottle. “Chateau d’Yquem? Isn’t that, like, five grand a pop?” she asked. Her eyes and smile widened.

“Seven-thousand five-hundred. Plus customs to have it flown in,” he said. He grabbed the bottle from her hand. “Not for you, though.”

She giggled. “Oh, right. I have to earn it first,” she said. She unbuttoned her coat as she stepped backward toward the bed. Vincent smiled, but didn’t move.

I scoffed and my nails stabbed into my palms. As I stood up, my head clanged against the metal railing inside the closet. “Shit!” I winced and stumbled out of the closet.

“What the hell?” Blondie asked.

My head throbbed, but I stood up straight. “What are you doing here with my husband?” I asked. My nostrils flared as she took a step towards me.

“Who the hell are you?” she asked.

“I’m—” I flinched as blood splattered across my face and lips. Blondie dropped to the floor. Behind her, Vincent lowered a gun with a silencer attached to the barrel.

“Go shower,” he said, placing the gun on the table. “I’ll take care of this.”

THE END

MOROCCAN BLUE

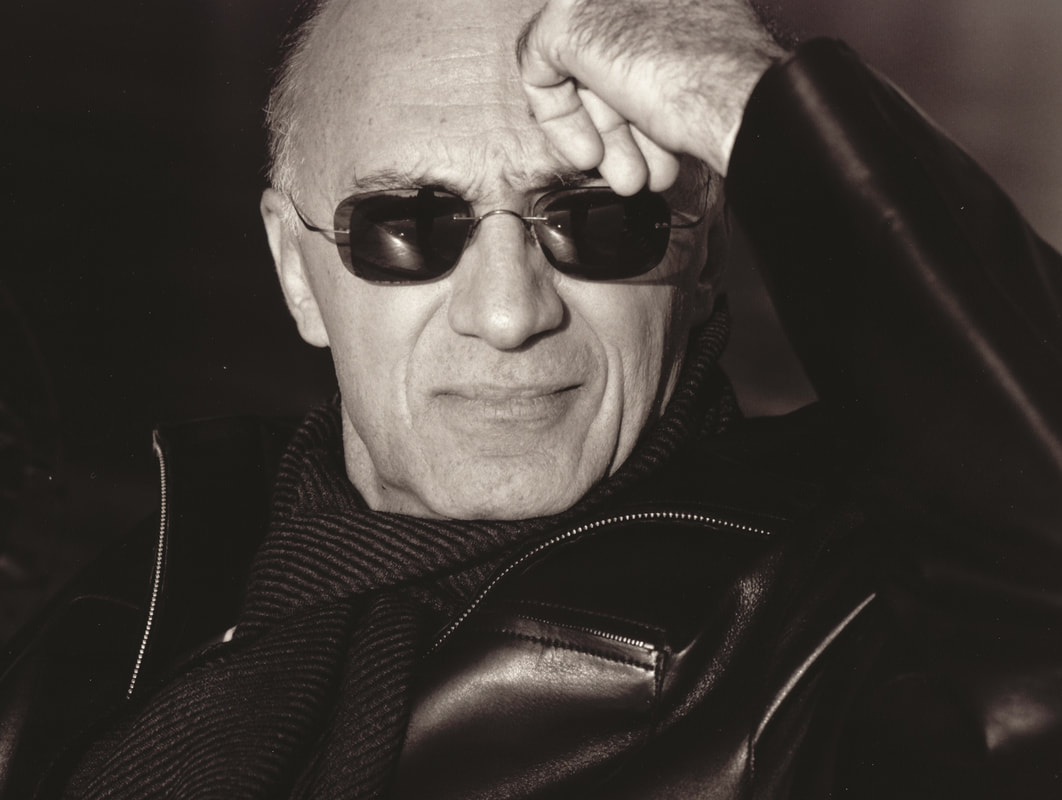

| Henri Colt is a physician-writer and wandering scholar whose passions include mountaineering and tango. He is the editor of Picture of Health: Medical Ethics and the Movies (Oxford University Press). His short stories have appeared in Rock and Ice Magazine, Fiction on the Web, Flash Fiction Magazine, and Fewer than 500. |

“I love the taste of semen,” Brigitte says, pouting her lips as only a French girl can. “Does that intimidate you?”

“I don’t know,” I say. “Should it?”

“It’s not something guys like to hear.” She stirs three teaspoons of sugar into an espresso. “I was with my boyfriend for seven years, but he dated other nurses. What about you?”

“I’m not married, if that’s what you mean.”

Brigitte sits forward, crossing her forearms on the table. There’s that pout again.

“So, they assigned you to a singles resort,” she says. “Sandy bays with blue-green waters at the foot of the Rif mountains. It’s not a bad way to spend the summer.”

“Well, it’s my first real job since graduation, and the recruiters said Morocco was ideal for romance.”

She cups her hands under her chin. I love the way she lifts her eyebrows when she smiles. Her blue eyes have the translucence of a Portuguese-man-of-war.

“I’m all ears,” she purrs.

“Your eyes are stunning.”

“I’m listening.”

“Seriously, they’re beautiful.”

It’s a Bogart-Bacall moment—seconds pass with no response.

“I like a man who is sincere—not very original, but sincere.” Her sun-bleached hair bounces over her shoulders as she breaks out laughing. She brushes the curls back and furrows her brow. When she takes my hand, her smile vanishes into the parentheses at the corner of her mouth, but there is a playfulness in her voice. “So, tell me, doctor. Do you seriously think we can be an item?”

Her eyes glisten. Small beads of sweat gather on her temples. Even in the shade of the resort’s First Aid office, the afternoon heat is smothering.

“It’s a club for singles,” she says, stroking my palm. “I don’t think you’re here to ogle me monogamously.”

A hoard of shouting children burst in. “Come quick, there’s been an accident!”

I jerk back my hand. “What?”

“A man is drowning.”

Brigitte bolts from her chair and grabs the red and white emergency medical kit. She strains to carry it. The kids push and pull her toward the door. “Hurry,” they shout.

“Hurry,” she says, throwing me a look over her shoulder.

I grab an oxygen tank from the storage rack. The heavy steel cylinder is about two feet long and five inches in diameter. Lifting it onto my shoulder, I remember to shove the regulator into my back pocket and rush down the steps toward the beach. The tank weighs on my clavicle. I run past several couples lounging on their hammocks. Music plays from the adjoining bar. People move aside to let me through to the boardwalk.

About fifty feet in front of me, Brigitte stumbles. She picks herself up, and still gripping the toolbox, starts running again. “Hurry,” the children scream. A younger one is crying.

Without flip-flops, my feet sink into the burning sand. I pant and plod across the open beach to catch up with my nurse. Sweat streams from her neck to the small of her back, shining like a thousand mirrors on her golden tan. She drags herself forward, kicking grit from thousands of crushed seashells in every direction.

An older child grabs the medical kit from her struggling hands and hoists it onto his shoulders.

“I couldn’t carry it anymore,” she gasps.

“It’s okay,” I say, catching my breath.

Several men are crouched by a teenager’s body. Their chatter roars over the whoosh of the surf.

“We just pulled the boy out of the water,” an older man says. Another takes the oxygen cylinder from my shoulder and drops it on the sand.

The kid looks like he’s sleeping. He’s maybe seventeen, with wavy black hair and stubble. The waves lick his ankles, and his legs are partially covered with wet gray slop. I grab him under the armpits and strain to pull him further onto shore.

“Move away!” I yell at the crowd. “Give me some room.”

I deliver a precordial thump to the kid’s chest. Holding my fist about ten inches off his breastbone, I deliver a second blow, but there is no response. I drop to my knees and begin chest compressions. And one, and two, and three, and four, and five, I count silently. Brigitte stands helplessly at the boy’s feet.

I pause for a breath between compressions. “Have you ever given mouth-to-mouth?”

“No,” she says. “Never.”

“Take over then.”

She kneels and stacks her palms on the kid’s chest.

“Don’t bend your elbows,” I remind her. “Lean onto your arms.”

“But, I’ve never done this before,” she pleads.

“Give him five compressions, then pause,” I say.

She pushes on the kid’s chest and counts, “And one, and two, and three, and four, and five...”

“Okay, stop for a second.” I pull a strand of seaweed from around the boy’s neck and throw it aside. I tilt his head using a chin lift. With one hand on his forehead, I pinch his nostrils and take a deep breath before wrapping my lips around his mouth.

He retches as I exhale. It’s more of a spasm than a retch, but he vomits all the same, and I cough violently, spitting and almost retching myself. I wipe my face with the back of my hand. Brigitte stops the chest compressions.

“Don’t stop,” I shout. “Keep going!”

The crowd circles. No one offers help, or if so, I don’t notice.

I ignore the sand glued to my face and fight a dry heave as I wipe foul-smelling sticky goo from my nose. I dig in my knees and sit on my heels. The kid’s eyes are open, but he doesn’t move.

I put my mouth to his and exhale into what feels like a bottomless container. I can’t feel his chest rise, so I try again.

Brigitte stops compressions and inches away from the boy. She’s sobbing. I thump once more on the young man’s chest.

“Brigitte, kneel across from me and try again,” I give the kid another breath.

Nothing.

Brigitte crouches in the sand. She keeps tossing her shoulder straps back on to keep her breasts from popping out of her bathing suit. With the sun in her face, she looks at me through squinted eyes. Her cheeks are flushed and wet.

“And one, and two, and three...” She leans into the boy’s chest. “Oh God,” she cries.

“What’s wrong?” I ask.

“I felt his ribs crack.”

This is a disaster, I think. Fuck.

“He’s not going to make it,” I say to no one in particular. Brigitte stops counting.

“He’s dead.” A man from the crowd steps forward. “He’s dead, I tell you.”

“Maybe not,” another answers. “They should continue.”

“No,” the first man urges, “he’s dead, I say. He should not have been in the water anyway. He couldn’t swim. Besides, only a fool goes in the water with an inner tube.” He shakes his head in despair.

I stop my efforts and look up at the crowd. I’m still on my knees, holding back the tears. “I couldn’t save him.”

Brigitte shudders.

“You did your best,” someone says.

“How do we know you’re a doctor?” a woman asks.

I glare at her but I don’t respond.

The police arrive, and onlookers describe what happened. Confusion reigns among shouts, arguments, and tears. “You should go back to the club,” an officer says. I shoulder the oxygen bottle, and silently, Brigitte and I drag the unopened medical kit back to the First Aid office.

“He had blue eyes,” she says when we arrive.

I close the door. Our lovemaking is immediately fierce and untamed, as if we could extinguish our anguish in the orgasmic bliss of a brief romance. We sleep that night in each other’s arms, but in the morning, with tears running down her sunburned cheeks, she tells me she is leaving.

“Back to my boyfriend,” she says. “I’m going home.”

END

“I don’t know,” I say. “Should it?”

“It’s not something guys like to hear.” She stirs three teaspoons of sugar into an espresso. “I was with my boyfriend for seven years, but he dated other nurses. What about you?”

“I’m not married, if that’s what you mean.”

Brigitte sits forward, crossing her forearms on the table. There’s that pout again.

“So, they assigned you to a singles resort,” she says. “Sandy bays with blue-green waters at the foot of the Rif mountains. It’s not a bad way to spend the summer.”

“Well, it’s my first real job since graduation, and the recruiters said Morocco was ideal for romance.”

She cups her hands under her chin. I love the way she lifts her eyebrows when she smiles. Her blue eyes have the translucence of a Portuguese-man-of-war.

“I’m all ears,” she purrs.

“Your eyes are stunning.”

“I’m listening.”

“Seriously, they’re beautiful.”

It’s a Bogart-Bacall moment—seconds pass with no response.

“I like a man who is sincere—not very original, but sincere.” Her sun-bleached hair bounces over her shoulders as she breaks out laughing. She brushes the curls back and furrows her brow. When she takes my hand, her smile vanishes into the parentheses at the corner of her mouth, but there is a playfulness in her voice. “So, tell me, doctor. Do you seriously think we can be an item?”

Her eyes glisten. Small beads of sweat gather on her temples. Even in the shade of the resort’s First Aid office, the afternoon heat is smothering.

“It’s a club for singles,” she says, stroking my palm. “I don’t think you’re here to ogle me monogamously.”

A hoard of shouting children burst in. “Come quick, there’s been an accident!”

I jerk back my hand. “What?”

“A man is drowning.”

Brigitte bolts from her chair and grabs the red and white emergency medical kit. She strains to carry it. The kids push and pull her toward the door. “Hurry,” they shout.

“Hurry,” she says, throwing me a look over her shoulder.

I grab an oxygen tank from the storage rack. The heavy steel cylinder is about two feet long and five inches in diameter. Lifting it onto my shoulder, I remember to shove the regulator into my back pocket and rush down the steps toward the beach. The tank weighs on my clavicle. I run past several couples lounging on their hammocks. Music plays from the adjoining bar. People move aside to let me through to the boardwalk.

About fifty feet in front of me, Brigitte stumbles. She picks herself up, and still gripping the toolbox, starts running again. “Hurry,” the children scream. A younger one is crying.

Without flip-flops, my feet sink into the burning sand. I pant and plod across the open beach to catch up with my nurse. Sweat streams from her neck to the small of her back, shining like a thousand mirrors on her golden tan. She drags herself forward, kicking grit from thousands of crushed seashells in every direction.

An older child grabs the medical kit from her struggling hands and hoists it onto his shoulders.

“I couldn’t carry it anymore,” she gasps.

“It’s okay,” I say, catching my breath.

Several men are crouched by a teenager’s body. Their chatter roars over the whoosh of the surf.

“We just pulled the boy out of the water,” an older man says. Another takes the oxygen cylinder from my shoulder and drops it on the sand.

The kid looks like he’s sleeping. He’s maybe seventeen, with wavy black hair and stubble. The waves lick his ankles, and his legs are partially covered with wet gray slop. I grab him under the armpits and strain to pull him further onto shore.

“Move away!” I yell at the crowd. “Give me some room.”

I deliver a precordial thump to the kid’s chest. Holding my fist about ten inches off his breastbone, I deliver a second blow, but there is no response. I drop to my knees and begin chest compressions. And one, and two, and three, and four, and five, I count silently. Brigitte stands helplessly at the boy’s feet.

I pause for a breath between compressions. “Have you ever given mouth-to-mouth?”

“No,” she says. “Never.”

“Take over then.”

She kneels and stacks her palms on the kid’s chest.

“Don’t bend your elbows,” I remind her. “Lean onto your arms.”

“But, I’ve never done this before,” she pleads.

“Give him five compressions, then pause,” I say.

She pushes on the kid’s chest and counts, “And one, and two, and three, and four, and five...”

“Okay, stop for a second.” I pull a strand of seaweed from around the boy’s neck and throw it aside. I tilt his head using a chin lift. With one hand on his forehead, I pinch his nostrils and take a deep breath before wrapping my lips around his mouth.

He retches as I exhale. It’s more of a spasm than a retch, but he vomits all the same, and I cough violently, spitting and almost retching myself. I wipe my face with the back of my hand. Brigitte stops the chest compressions.

“Don’t stop,” I shout. “Keep going!”

The crowd circles. No one offers help, or if so, I don’t notice.

I ignore the sand glued to my face and fight a dry heave as I wipe foul-smelling sticky goo from my nose. I dig in my knees and sit on my heels. The kid’s eyes are open, but he doesn’t move.

I put my mouth to his and exhale into what feels like a bottomless container. I can’t feel his chest rise, so I try again.

Brigitte stops compressions and inches away from the boy. She’s sobbing. I thump once more on the young man’s chest.

“Brigitte, kneel across from me and try again,” I give the kid another breath.

Nothing.

Brigitte crouches in the sand. She keeps tossing her shoulder straps back on to keep her breasts from popping out of her bathing suit. With the sun in her face, she looks at me through squinted eyes. Her cheeks are flushed and wet.

“And one, and two, and three...” She leans into the boy’s chest. “Oh God,” she cries.

“What’s wrong?” I ask.

“I felt his ribs crack.”

This is a disaster, I think. Fuck.

“He’s not going to make it,” I say to no one in particular. Brigitte stops counting.

“He’s dead.” A man from the crowd steps forward. “He’s dead, I tell you.”

“Maybe not,” another answers. “They should continue.”

“No,” the first man urges, “he’s dead, I say. He should not have been in the water anyway. He couldn’t swim. Besides, only a fool goes in the water with an inner tube.” He shakes his head in despair.

I stop my efforts and look up at the crowd. I’m still on my knees, holding back the tears. “I couldn’t save him.”

Brigitte shudders.

“You did your best,” someone says.

“How do we know you’re a doctor?” a woman asks.

I glare at her but I don’t respond.

The police arrive, and onlookers describe what happened. Confusion reigns among shouts, arguments, and tears. “You should go back to the club,” an officer says. I shoulder the oxygen bottle, and silently, Brigitte and I drag the unopened medical kit back to the First Aid office.

“He had blue eyes,” she says when we arrive.

I close the door. Our lovemaking is immediately fierce and untamed, as if we could extinguish our anguish in the orgasmic bliss of a brief romance. We sleep that night in each other’s arms, but in the morning, with tears running down her sunburned cheeks, she tells me she is leaving.

“Back to my boyfriend,” she says. “I’m going home.”

END

| Astrid Morales is a secretary by day and a writer by night. She earned a Bachelor's degree in Creative Writing from The University of California, Riverside in 2017 and currently, volunteers as a writing tutor for the International College of Christian Ministry (ICCM). She lives with her family and dog, Bartholomew. This is her first publication. |

DEALING WITH FAMILY

Cash walked out of his house, his windbreaker hiding the fact that he had something other than his uniform on. It had been a month since he was dismissed from school, and he hadn’t yet told his family. As he walked to the bus stop, he watched as the first few mobs of kids from the town of Primavera went to school. He missed being in that crowd with his friends, Nathanael and Hailigh, cracking jokes and worrying about what book they were going to read next. Any other kid probably would have been happy not having to go to school, but Cash needed to finish his year of career training to get that English teacher job he had been working toward. Then he could help his family and get out of Primavera.

Cash put his hood up so no one would take notice of him. He hoped to bypass The Elders of the town. The Elders were the law of Primavera. They roamed as they pleased and were allowed to stop anyone for any reason. They all came from the same family, the Garcias, that had founded the town in the year 2025. Primavera was small, surrounded by mountains in an area of what was once considered the region of Central America before the ongoing and rampant violence caught the attention of more powerful states that reasoned that the only way to be rid of the issues there was to destroy it.

The Garcia family, one of the few that refused to leave their lands and managed to survive the destruction, lamented the loss of what they knew. However, they attributed the misfortune their home befell to the region’s inability to stick to tradition and the things that were mandated by nature, such as male breadwinners and female homemakers. When the family founded Primavera, they vowed to take it back to simpler ways and thus created rules for the safety of all. As a result, it was isolated. People rarely went into Primavera except to take pictures of the quaint town with little pollution, limited technology, and a dependence on agriculture and mom-and-pop businesses to stay alive. Not many left Primavera unless they had a job outside the town, for everyone had what they needed. Or at least it seemed that way, because to want more than what you had was to be ungrateful and disrespectful toward what had been built.

Cash walked through the tiny streets and saw Bernal’s hardware store, his mother’s tortilleria—closed because of the early hour—and Darlin’s snack shack, where he had been fired because he was a boy and Darlin hadn’t wanted to pay him his appropriate wages anymore. She had said it was because she needed to save money. Cash couldn’t believe that the best thing Darlin could come up with to save money was getting rid of him rather than being more careful when doing inventory. Despite Cash advising her to focus on ordering things that people needed and always bought, Darlin still ordered things that weren’t selling as well. What did Cash expect, though? Darlin hardly listened to him. It was her shop. Cash had sarcastically wished Darlin good luck because he was supposed to be replaced by a girl, but no girl would be able to close for Darlin at midnight the same way he did. It backfired on Cash, though. Darlin told him that his disrespect would cost him.

Cash hadn’t believed her. However, as he scouted the town for a new job, no one wanted to hire him. Darlin had warned everyone that he had no respect for his older counterparts and that he wasted time on the job talking to girls hours on end.

Cash didn’t try fighting off Darlin’s half-truths with any possible new employer because even though Cash was a guy, Darlin’s ten years over him held more weight, and her inheritance of her father’s store after his death made her more important in the town. She was one of the lucky women. Her father had no male children, so everything he had was hers. Cash, unfortunately, was only eighteen and owned nothing. Though after his father’s death the tortilleria was meant to be his, his mother had assumed ownership of it because she wanted Cash to have the opportunity to do something else. At least that’s what she said when she had still had control of all the family’s money issues after her husband died.

Tons of people crowded around the third and final bus stop of the town. Cash looked around for Ignacio, one of the children of The Elders. He was training to be the eyes of the town, because his father, like everyone else’s, would not last. There were other children, but Ignacio was not a man anyone liked to meet. For one, he was at every Teaching.

When Cash didn’t see him anywhere, he waited for the Lucia. He took a book out of his backpack so he could pretend he wasn’t going to be behind in his schoolwork. No one paid much attention to him, and he liked that. Cash kept reading as he hopped on the bus to the city of Mar-y-Sol, where he would go and sell that day’s stash of weed.

There were two rules for selling under Oliver and Enoch. One was not to sell in Primavera because of The Elders, and the other was always double profit. Oliver and Enoch said the more people Cash could find to be regulars, the more money he would make. Cash sometimes wasn’t sure if all the traveling or the risk was worth his newfound profession, but by one-forty in the afternoon, he had made ninety bucks. He stopped thinking about risk. Cash hoped to make the same tomorrow or maybe more. Hopefully more, that way he could go back to school sooner and keep saving up to stop living in Primavera, where nothing moved forward.

Cash sat in his usual spot on a bench in Mar-y-Sol’s Baralyme Park. It was in front of a fountain where the water changed colors. From the first time he saw it, he was fascinated. The water was red at the moment. It looked like diluted blood to Cash, and he wanted to touch it, but he knew if he stood up he might miss his sale. Cash kept his hands in the pockets of his windbreaker. He played with the tiny bags of mota. He only had five little bags left to get rid of, and the regular he had found there would take three. She usually took three. Today, though, the girl held back and only bought two little bags. Cash had to figure out how to get rid of her other usual bag.

Enoch and Oliver weren’t demanding of Cash, but the first time he didn’t sell everything they had given him, they took more than half of what he had made for that day, even after he doubled profit. He ended up with ten bucks. Cash complained to Hailigh about her brothers, but she just shrugged and said that was business with them.

Cash walked into the bathrooms closest to the fountain where he met up with a guy he was afraid of selling to but couldn’t turn away because of his loyalty. By comparison, the guy stood at least a foot taller than Cash with a much bigger frame; Cash’s limbs were pine needles next to him. Today the guy decided to complain to Cash about the quality of the stash from last week. The only thing Cash could tell him was that if he wanted to complain to the twins, he might as well take Cash’s place. This amused the regular, and he told Cash he’d never end up like him, a drug dealer.

Cash wanted to tell the guy he’d be lucky to end up like him. Cash was third in his class, almost done with the career section of his schooling, making money, and there was this girl that loved him and…Cash didn’t know what else to imagine shoving in the guy’s face, but he was sure there were other things. There was nothing wrong with being him. At least Cash had something he was working toward. Whether or not it was approved of didn’t matter to Cash.

When he finished for the day, Cash waited for the Fernando to take him home. He smelled his hands and noted that the scent of mota hadn’t left. The Fernando dropped Cash off in front of the sign welcoming everyone to Primavera, “The Town Where Time Stopped.” Cash snorted and walked toward the Serpent River. He was glad it wasn’t far from there. He ran through the String Forest and hoped he wouldn’t get bit by too many mosquitos. He was tired of the itching red welts that appeared on his light skin whenever he spent too much time there.

Even with the sun at its peak, the trees only let tiny streams of light through. Cash tripped and ate dirt. As he picked himself up, he saw that his already mutilated rain boots sported mouths. He walked with them in hand so he wouldn’t trip again. Once at the river, he checked the small pocket of his backpack and thanked God for the orange lump of soap he had packed a few days ago. He took off his clothes, only leaving on his underwear and undershirt. Cash ignored the giggling women already at the river hand-washing their clothes as usual.

Cash dipped his clothes in the water and rubbed the orange soap into his windbreaker, shirt, and pants evenly. He scrubbed each item at the bottom of the river against the smooth stones and wrung everything out a couple of times. The smell of tangerines pervaded his clothes. He pulled a plastic bag from inside his backpack that contained his uniform and dressed up with his back to the women. He didn’t want them to see what school he was from or used to be from. He wondered if the colors would give him away, but only the girls really had enough diversity in color of uniforms to be identified with a school. Boys usually had blue, navy blue, white, black, gray, and beige. Of the five schools in Primavera, each had the boys wearing some mix of those colors. Cash only had to worry about the emblem on the cardigan. He put the wet clothing in the bag and ran home. Or he tried to. He had no spare shoes.

Cash saw his sister Salma walking with her friends. All the girls matched in blue dresses and red cardigans, the official uniform of Madrigal Academy. As Salma smiled wide, Cash saw the dimples she shared with their mother. He was glad she was happy. Cash watched her a bit before trying to get away.

“Pisto! Wait up.” He stopped walking. He hadn’t been fast enough. Salma half-hugged him when she caught up. She pointed at his shoes. “What happened to those?”

“Not important.”

“So, where were you today?”

“Just taking care of business.”

“What business?”

“You want five dollars when we get home, don’t me questions.”

“Maybe I want ten.”

“I could give you ten.”

“Do you know what I could do with ten?”

“Invite your friends to ice cream?”

“Invite one of your friends to ice cream.”

“Why would you do that?”

“’Cause he has pretty eyes.”

“Nathanael has a girlfriend.”

Cash and Salma made their way up the hill to their house.

“So, I shouldn’t take him out for ice cream?”

“No, you shouldn’t. He’s old. You wouldn’t take me out for ice cream.”

“But we did that for your birthday.”

“Stop it.”

“You’re going out with his older sister.”

“That’s not that same.”

“You sure?”

“Yes.”

Salma shrugged, “I guess.”

A couple of their mother’s chickens greeted them by the front door. Salma went into her room and Cash went straight to the back, where he put his clothes to dry on the line. It didn’t look like his mother was home. Good.

Cash went to his room to count the money he had made and to make sure nothing had been lost when he went to the river. After he finished, Cash put the money in an envelope and noted that the tins on his desk and on his nightstand in which he hid money for his mother to find were empty. Of course they were. Some days she was slicker and tried to put money back, but it was never the same amount Cash had left.

Under his bed, beneath a pile of clothes, from inside his old broken lunch box, Cash pulled out a small burlap pouch that had Egyptian-blue buttons across the top. His name was spelled out in white ink on the buttons. His father had bought it for him when his family went to the city of Gloria. As he held the pouch, he remembered the beach with its impeccably blue water and soft, thick, black sand. He and Salma spent time catching sand crabs together and collecting shells. The two roamed the city with their mother while their father was busy. Cash had marveled at the infinite amount of high-rise buildings close to the sea, each a different vibrant color. He had loved looking at the sun reflecting from the windows. He wished to stay forever, but the deal to move the tortilleria fell through.

Cash checked his savings. After pulling out a ten for Salma, he saw that his mother had taken even more money from him. He was getting tired of moving his money around from hiding place to hiding place. How could he ask his mother to stop taking from him, though? He needed to be saving, but he knew his mother couldn’t possibly take care of all their needs with only the tortilleria, which wasn’t even doing well, no matter what she said. Cash rubbed his face. Why couldn’t she just ask for help or directly ask for the money? He’d take on more sales for Oliver and Enoch. He’d take a job in another town, too, even if he wasn’t sure how that worked. Anything to keep his family from drowning and for the chance to leave Primavera behind.

Cash went to Salma’s room and shoved the ten under her door.

Her door swung open and she said, “I was only joking!”

“Yeah, but I wasn’t.”

“Pisto, where are you getting all this money?”

“You don’t need to know.”

“But I want to,” she whined. “Then, in case you break up with Careena, I can tell my friends that you’re nice and you take care of me and Mamá.”

Cash furrowed his brow. “What are you talking about?”

“Well, all the guys suck. You’re like, alright. Maybe you’ll end up married with someone here.”

Cash choked on his saliva. “Why are you even thinking about that right now?”

Salma shrugged. “All the girls are talking about it. Well, okay, a lot of them, but mostly I think it’s the Home Ec. class, ’cause we were supposed to do some assignment on an ideal partner, and then we started working with the boys that, like, kinda matched. I got Dario Galvez. Which, you know, he’s okay. I’m not marrying him, though.”

He hated this town. “Please don’t marry anyone right now. Go do something with your friends. Not mine. Yours. And never mind your assignment. Be a kid, will you?”

“Well, I’m not an adult.”

“Right. Go out.” Cash looked at the time on his beat-up phone. “Just be back soon.”

Salma hugged Cash and rushed out of her room. Cash let out a heavy sigh after he heard the front door slam.

Cash went out to feed his pet rooster, John-Henry, and his mother’s chickens. He watched as the birds ate, and when they were done, John-Henry followed Cash as he walked back inside. His mother constantly told Cash not to let the rooster in, but since she wasn’t home yet, he let John-Henry hang out while he collected the trash from the bathroom and the kitchen. Cash put everything in the large silver can he shared with his neighbors. His mother wouldn’t be able to say he never did anything if she was in one of her moods when she got home. Cash motioned John-Henry outside and then collected water from their little well. With the watering can he got his mother two years ago as a birthday present, he began to water her garden. Cash knew how much she appreciated him doing that, especially after she had found his father dead in the garden. It was a stress-related heart attack that took him.

Three days earlier his father had taken the family out of Primavera to show them where the tortilleria could be moved or even where they could go without it.

“Fausto, si estamos bien allá,” Cash’s mother complained.

“Aurélie, solo quiero que veas las posibilidades.”

Aurélie fell asleep during the bus trip, but her children didn’t. Salma and Cash watched the dirt road surrounded by trees and tall grasses transform into concrete. As the bus rolled forward, they saw they were surrounded by impressive cars. Cash longed to know what it felt like to drive one, to be as relaxed as the woman next to the bus in a red car, her hair billowing and her voice carrying over the traffic. Cash wanted to know what was so funny. What was it that blinked blue inside her ear? Salma wondered where the woman was going and who let her have a car. Was she an only child? Salma looked at Cash. He’d probably be the one in the family with a car, if they needed it. But in Primavera, there was no use for cars. You could walk or bike to get to wherever you wanted.

The family walked through a different town to get to a train station and go to Esmeralda. Esmeralda was a place of constantly improving technologies from areas dedicated solely to wind-turbine manufacturing and the development of sea launderers, which helped clean long-lasting oil spills. Cash loved it there. Of everything he saw in the city, nothing fascinated him more than helping his grandmother with laundry and watching the clothes spin. It felt right. Normal. Salma liked the electric stove oven. She enjoyed watching the cookies that her grandfather made rise. She could also flip tortillas for dinner without being afraid of fire licking her. The children pleaded with their mother to stay longer than the day. She was the one that always needed convincing.

Aurélie had no intention of staying longer than she needed to. She spoke with Fausto about how uncomfortable she felt in Esmeralda, how he could not ask her to leave behind what she knew. Even the day felt like too much for her. Fausto didn’t understand, being a native of Esmeralda, but he understood the sacrifice he made to leave everything he loved behind for Aurélie. He only moved to Primavera to marry her and do it according to the rules. He would not make her struggle for his sake.

Cash’s family had not been back there since his father died, and Cash’s grandmother refused to talk to his mother because she still believed Aurélie had stolen her son Fausto’s future.

Cash heard the back door slam, and he knew his mother was home. “Cash! Cash Manolo Alarcón! ¡¿Dónde andas?!”

His middle name never meant anything good.

“Aqui, Mamí,” Cash said as sweetly as he could. What hadn’t he done this time?

“Don’t ‘Mamí me!” His mother rushed at him. She pulled him by the ear and Cash bit down on his lip. “Your school called about money and collections or something like that. They said you hadn’t been there in weeks. Where have you been going?” She let his ear go.

“Around. I’ve been working.” Cash held his ear.

“Where, huh? Darlin fired you. That I know. I swear, if I hadn’t paid the phone bill, you wouldn’t tell me anything.”

Cash almost rolled his eyes. If she hadn’t.

He said, “You don’t tell me anything either. Why do you think I’m out? I trusted you. You said you would be able to pay the rest of my test fees and tuition and you didn’t. Do you know how ridiculous I felt begging the administration office to check again and again in my files because there must’ve been some mistake? Why are you acting like it’s some big surprise I’m not there? You should have just told me you couldn’t help. I would have figured something out by myself when I still had time.”

“I needed to save up more money to make sure I had enough for Salma’s tuition. I-I thought I’d eventually have enough for yours, but that didn’t happen, and I had to figure out how to pay for some equipment that broke at the tortilleria. I thought with your grades maybe something would work out.”

“That’s not how it works.”

“Well, your father was always telling me how you were helped because of them.” Cash’s mother shook her head. “I never had a problem with the school until the money your father had finished anyway.”

Cash looked at his mother. “You didn’t tell me Papá left money.”

“You didn’t need to know that. You weren’t going to be in charge of it.”

“What happened to it?”

“What do you think? We lived off of it for as much as we could.”

Cash wanted to believe his mother. “Mamá, are you sure?”

“Of course! Do you think I’d let us starve?”

Cash didn’t know what to think, but he said, “No, you wouldn’t.”

“Did you forget I am the mother? That I am the one that makes this household run?”

His mother’s smug smile was the last straw. Cash threw the watering can. “You’ve been taking my money. We’ve been cruising on my savings these last two weeks. I’m just as responsible as you are. You’re not the only one doing something for our family.”

“The money is under my roof, so I use it for what is necessary. You were going to use it for some silly trip when we have more important things to worry about.”

“Wanting to leave Primavera is not silly. Mamá, if you hadn’t started taking my money, I wouldn’t be in this mess!”

“Don’t yell at me, ¡patojo malcriado!”

Cash clenched his jaw and took in a breath. “I’m sorry,” he said, not meaning it. His phone rang in his pocket.

“Don’t answer that.”

Cash fished his phone out and saw Hailigh’s name on the screen. “I have to go,” he said softly.

Cash picked up the dented watering can and put it into his mother’s hands. She watched him leave and then futilely tried to get her watering can the right shape again.

Cash boarded the Lucia once again to Mar-y-Sol. He saw the huge mall and walked the rest of the way to the back of the Sunflower Movie Theater, the money envelope in his hands. Cash was always amazed at how nice even the back of the theater looked. Every time he went, it was like the first time. When would he ever be able to go in? He heard it was beautiful inside and that, should you order food, they brought it to your seat.

Primavera had no such thing as a movie theater.

Hailigh, her brothers, and Nathanael were already there. Hailigh’s brothers seemed to be intimidating someone. They were obnoxiously telling the guy what to expect when selling for them. On occasion, they punched the guy’s shoulder. Cash learned it was their way of showing affection. They had done that to him. He wasn’t scared of the twins despite the height difference and the fact that they had worn tanks the first time they met for dealing to show off the scars left on their shoulders from encounters with The Elders of Primavera. Perhaps it was Hailigh’s resemblance to them that made Cash think they were softer. Hailigh and the twins shared round cheeks, long eyelashes, and curly, brown hair.

Nathanael was leaning on the back wall of the theater, still in his uniform, the Candelaria Academy cardigan around his waist and his satchel over his shoulder, a cigarette he probably thieved from his mother at his lips. “Hey, Orejas! We finished the weird book today,” he said and crushed the cigarette with his white sneakers before getting near Cash. He knew Cash hated the smell.

It would be especially awful if the scent stuck around in Cash’s hair. Nathanael knew how well Cash took care of his hair. There was pride in it, which Nathanael would make fun of if it were any other guy in town, except Cash’s hair wasn’t just about looking good. In all the time Nathanael had known Cash, he had never seen Cash with his hair cut short.

When they first met and Nathanael had mocked Cash, saying he should get rid of it before he got lice, they clashed. Outside the principal’s office, Cash had told him it was about his father. His father had taught him how to wash it properly. He even cut it for him. A year after Cash’s father died, Cash had found a picture in which his father had his hair as long as he did. The resemblance had made Cash happy.

Cash moved his hair from behind his ears. The very top of his ears would still peek through, but he felt less self-conscious about them being under the curtain of his shoulder-length black hair.

Nathanael smiled at Cash before giving him a half hug. “Prof. Renato misses you, bro. He looked ready to tear off his face today when no one talked about what we thought of magical realism.”

“Did you try to say something, Narizón?”

Nathanael smacked Cash for making fun of his nose and said, “Pshh, no. You know I don’t know what’s going on in that class.”

Cash laughed. “You want help with the final paper, then?”

Nathanael held the back of his neck. “Yeah. Oh, and Careena sent you something.” Nathanael dug into his pockets for it.

“Really?” Cash tried not to sound too excited. He didn’t want this to be more awkward than it already was. “So, uh, what did she send?”

“Wait, will you? It’s not like she didn’t send you something else this week.”

Since Cash had gotten involved in his new profession, he spent even less time with Careena than he wanted, if that were possible. The “girls” Darlin mouthed off about were really only one. Cash’s girlfriend would talk to him a maximum of five minutes when she could visit him at Darlin’s place. Careena wasn’t allowed out of the house for long, and she definitely wasn’t allowed near Cash after her father had caught them kissing in her backyard once. Mr. Vega had called Cash a long-haired heathen and had warned him that if Cash ever put his daughter’s honor in jeopardy again, there’d be consequences.

Cash missed watching Careena walking in her heels on her usual route to the Ilumina bank because he had to get on the Lucia to Mar-y-Sol as she began her walk each day. He missed seeing the difference between her gray pencil skirt and pink top and all the other girls in uniforms he encountered. He also missed the morning conversations about how her training was going. He didn’t understand much about accounting, but when she talked to him, he was fascinated by numbers and her soft voice.

They’d often talk by meeting up at the library with Nathanael so it seemed like Cash and Nathanael were going to hang out. On the weekends, they arranged to meet at the computer lab. Careena would go under the pretense of needing to do research for something, but Cash simply asked his mother if he could go out for a couple of hours. They wouldn’t sit together because Careena was wary of the people who attended her father’s church. They could be just as bad or worse than her father in judgment, and they could easily tell her father she was out with a boy who wasn’t her brother. The safest thing to do was IM. Often it felt silly, since they were only a couple of seats away from each other, but they took whatever opportunity they had.

“Here you go, Romeo.” Nathanael handed Cash a pack of strawberry cookies and two boxes of gum.

“Don’t call me that.” Cash ripped open a box of gum. There was no difference in flavor, but Cash liked to eat the red ones first. He handed Nathanael the box so he could pick out the green ones he liked.

Hailigh and her brothers dismissed the person they were talking to.

Enoch asked, “You brought the money?”

Cash nodded, and Enoch took the envelope and counted. He split his half and his brother’s, then put the rest of the money in the envelope for Cash to take back.

Oliver took a small bag from his pocket. “Tomorrow you’re going to Franela. We’ve got a few people asking out there, and you’ve spent too much time in Mar-y-Sol anyway.”

“Is it nice? I’ve never been there.”

Oliver frowned. “I guess it’s okay. You’ll go tomorrow, no big deal. Just do the same thing. Now go home, Melena. You can’t be with us too long.”

Cash ignored the nickname.

Hailigh told her brothers she’d see them at home and took Nathanael by the hand. Cash walked next to them. “So, how do you like it?” Hailigh asked.

“It’s not as bad as I thought,” Cash said and scratched his head.

“Told you. The important thing is not to get caught back home.”

“I’ve been careful.”

“You better be. You don’t want to end up like my brothers.”

“Are you, um…did you ever get…” Cash rubbed his shoulder. He wasn’t sure how to say it.

“Oh, no. Well, kind of. It’s different for girls, and the only reason I got into trouble was because I knew what my brothers were doing and didn’t say. The Elders just got rid of my hair. I was younger then, anyway,” Hailigh said. “As long as no one says anything back home, I can’t get in trouble again.”

“I bet you looked cute with short hair,” Nathanael said.

“My haircut was awful.”

“You could never look awful.”

“Shut up.” Hailigh softly knocked her head with Nathanael’s.

There were numerous people with shopping bags walking around the three of them. Mothers pushed strollers with napping babies in them. Kids still in uniforms with ice cream cones in hand took silly pictures. Cash thought of Salma.

“What do you guys think about getting married?” Cash asked.

“You’re not trying to marry my sister, are you?” Nathanael asked.

“No!”

“So, you’re using my sister?”

“That’s not how I meant it.” Cash pushed Nathanael when he saw him smiling. “This is about my sister.”

“Who’s she trying to marry?” Hailigh asked.

“Maybe your boyfriend. I don’t know.”

The two looked at Cash and laughed.

Hailigh said, “Why are you worried about a crush? She’ll get over it.”

“It’s not the crush. By the way, Nathanael, if my sister asks you to get ice cream with her, take Hailigh with you.”

“Noted.”

“So, what’s the problem?” Hailigh asked.

“That she wants to figure out who to marry right now. I mean, do you know you’re going to marry Nathanael right now? Have you known since you were fourteen? They’re assigning people to each other now in Home Ec. We didn’t do that.”

“You’re being a viejito. Maybe The Elders thought they could pair people up younger so Primavera doesn’t die out. I don’t know. I’m sure it doesn’t mean anything.”

“Isn’t it a little weird? I mean, listen to yourself. What if The Elders are trying to match-make kids?”

“If you make a big deal out of it, then it is. Us girls have been conditioned for marriage, remember? We don’t have the luxury of just hanging out and doing whatever like you guys do. We have to figure out how we’re going to be taken care of because I’m sure not inheriting my dad’s barbershop. I don’t even know how to cut hair.”

“I could take care of you.” Nathanael said.

“We’re not talking about that right now,” Hailigh said.

Nathanael looked at Cash. “See what you did?”

“I didn’t do anything.”

“He didn’t do anything,” Hailigh said and kissed Nathanael’s cheek. “Maybe some other time, Piel Canela.”

“Sure.” He beamed.

“Alright, whatever.” Cash looked at some of the stores beside the Sunflower. “Do either of you know where I can get new rain boots? Mine died today.”

“I know a place.” Nathanael pulled Hailigh along, and Cash followed.

They went up two sets of escalators and squished between people to get to where Nathanael wanted: Picador Shoes. Cash had never seen so many shoes in one place. Most of the shoes he had were hand-me-downs from his cousins, which was why they never lasted him too long. The stores in Primavera had at most four different kinds of shoes for both men and women. There were so many styles to choose from here, though. Cash looked at the tan work boots, the sleek sneakers, and the checkered slip-on shoes. He had to remind himself he came for plain black rain boots. He chose a kind with a good grip at the bottom so he wouldn’t fall when the dirt of the hill back home turned to sludge on the days that began with rain.

After choosing his shoes, Cash looked at the women’s section. His mother’s loafers were starting to look dingy. Should he get her a new pair now or wait a little longer? He had left her behind angry. If he bought her something now, she might ask where Cash got the money. He was not going to tell her. Cash grabbed a brown loafer and poked the inside; it was squishy. Maybe he could have the store hold them.

“You know those are designed for women, right?” Cash heard a soft voice behind him. He turned and saw Careena smiling at him. “Where’s my brother?” she asked, looking around the store.

“Sitting in the back. Probably making out with Hailigh.”

She rolled her eyes. “You take such good care of my baby brother.” Then she smirked. “Let’s go ruin the moment.”

Cash walked behind Careena and fought the urge to run his fingers through her wavy black hair. It usually wasn’t down. Her preferred style was a bun. With her glasses and the clothes she wore to work, she looked like a stereotypical secretary, but right now she looked like any nineteen-year-old girl in jeans, a t-shirt, and tennis shoes. Careena squeaked and made a big deal about finding her brother. Cash put his hand over his mouth, trying to suppress his laughter.

Nathanael’s eyes went wide. “Why are you here?”

Careena put a hand on her hip. “Why aren’t you happy to see me, Small Fry? Hurry up and hug me.”

Nathanael got up, annoyed, and hugged Careena. Then Careena hugged Hailigh. She held onto Cash the longest. Cash noted that Careena’s hair smelled like lemongrass.

Cash smelled grimy and familiar to Careena. She let him go abruptly and studied his face. She looked at her brother and Hailigh. It couldn’t be. Not her Doe Eyes.

“Papi is somewhere downstairs trying to find new ties for his retreat next week,” Careena said quickly. “I, um, I convinced him to let me come up here to look at shoes.” She ran her fingers through her hair. Nathanael and Cash recognized her nervousness. The rest of Careena’s words were lodged in her throat.

“Are you okay?” Cash asked.

He was kind. He was beautiful. He didn’t mind sneaking around despite the threat of her father. He wanted to do something with his life. Cash was good. He had to be good. Yet there was the smell. The longer Careena stood near him, the more she felt the stench penetrate her every pore, and she wanted to scrub it out.

“I—it was a mistake coming up here. I have to go.” Careena pushed past Cash and walked out of the store.

“Can you buy these for me, please?” Cash asked Hailigh, putting his rain boots on her lap and setting money down on the box. “Let’s go,” he told Nathanael and pulled him along.

“You know this place is huge, right? If we don’t find my sister—for all we know, we’ll find my dad, and I’m not supposed to be here.”

“And I’m not supposed to be your sister’s boyfriend, but it’s too late for that.”

“If you’re fighting, what does that have to do with me?”

“I didn’t know we were fighting, and you know I can’t be alone with her!”

“Calm down.” Nathanael tugged down on Cash’s hair. “We’ll find her, and you’ll fix it.”

Careena wasn’t far, but she walked briskly. Cash and Nathanael caught up to her in a couple minutes. “What’s with you, ’Reena?” Nathanael asked.

“I don’t want to talk to either of you.”

“C’ mon.” Nathanael grabbed her by the wrist.

Careena ripped her hand out of her brother’s grip. “Don’t touch me.”

“What happened? Did I do something?” Cash asked.

“Why do you ask me that so innocently?”

“So, you have stuff to work through,” Nathanael said. “I’m gonna go back to Hailigh.”

“You’re not leaving until we’re done,” Careena said and flicked Nathanael’s ear.

“Tell me what’s wrong,” Cash said.

“You.”

She had never spoken to Cash like that before. Not even when she had the right to be mad when he missed her birthday last year because it was the middle of final exams. She had gone to the library for him and left him coffee and sweet bread instead in response.

“What?”

“You heard me.” Careena crossed her arms.

“I haven’t done anything.”

“Really?” Careena put her tongue in her cheek and pulled Cash by the sleeve of his hoodie toward a single-stall bathroom by an elevator. She looked around before pushing Cash in. “You guard,” she commanded Nathanael.

“What’s wrong with you?” Cash asked once Careena locked the door.

“Why do you reek of weed? Don’t you know what The Elders do to people that have it, that smoke it?”

Cash stood there dry-mouthed.

“Do you want to see what they do?” Careena took her shoes and socks off. Cash saw the evenness of her brown skin end at her ankles. Stripes of scarred flesh covered her feet. “So, what are you doing?” Careena crossed her arms.

Cash ran his hand down his face. Careena was going to hate him. “Dealing.”

She let out a heavy sigh. “Why?”

“I don’t…” Cash wasn’t sure what to say. What would Careena do if he told her? What if he didn’t? “Money. I need fast money.”

“You’re smarter than that. You’re also a guy. You can do more and better.”

“Yeah, but that didn’t work out for me when I got fired. I just wanted enough to get back to school. You know how much I love it. You know how much I need it.” He sighed. “I don’t expect you to get it, since you and your brother don’t have to worry about money, but don’t try to give me some speech about my possibilities.”

“Cash, just because my dad has money doesn’t mean he shares it with me. He thinks women shouldn’t handle money.”

“Then how are you even in accounting?”

“I told him after I had the diploma and the bank picked me up because of my grades,” Careena said. “In the end, it’s not like he cared about what I was going to do with my life. I’m just supposed to get married and have kids. You know my father. He takes The Elder’s rules too seriously. It’s a wonder he ever let me go to school in the first place.”

Cash pointed at Careena’s foot. “So, when did that happen?”

“A few years ago. I was selling for the money, too.” Careena scratched her arm. “Then I smoked. I loved the smell. All of it was freeing. Then I got sloppy, got caught, and because I am my father’s daughter, he had me punished with hellish fire.” Careena rolled her eyes and leaned against the door. She looked small. Her soft voice back, she continued, “My dad didn’t want it public because he said no one would be my husband if they knew what I had done. It was his way of straightening me out.” Careena shrugged. “It, uh, it w-worked.”

She mustered up what she hoped was a smile although her eyes were watering. Cash wasn’t quite sure what to do. Careena was not a crier. He walked over and leaned on the door with her. She grabbed his hand. “Sorry for being so angry,” she said. She moved Cash’s hair behind his ear and ran her thumb over the edge of his ear.

Cash smiled. “It’s okay. I’m sorry I didn’t tell you. You’ll have to tell me why you’re mad at me next time we fight, though.”

“I can do that. We’re not fighting about this again, though, so can you promise me a couple things?”

“Okay.”

“My brother can never get into any of this stuff because of you. And promise you’ll leave the selling, that you’ll find something else. I know you can. I don’t want anything to happen to you.”

“On my nonexistent grave, your brother won’t get into drugs because of me, and I’ll find something new.” Cash kissed Careena’s forehead.

“Thank you.”

“We’d better get out of here before someone starts looking for you.”

Careena nodded and unlocked the door. Nathanael was still there standing guard. She hugged her brother from behind and said, “Let’s go.”

“But Hailigh—”

“I need your help. Tell her you’ll see her tomorrow, please?”

“Fine, but you owe me.”

“You have no idea.”

Cash waited for a moment and then left the bathroom. Hailigh called him a few minutes later. She’d meet him at the bus stop because they were going home together. Nathanael had some errand at the bank to run with Careena.

When the two got on the bus to go home, they saw Don Mincho, Head Elder of Primavera, his white western hat with the blue feathers on his head as usual. He was sitting in the back looking out the window. Don Mincho was seventy and still walked with heavy footsteps like a twenty-five-year-old. His leathery face and white hair gave him away, though.

Hailigh told Cash to close his eyes and keep his mouth shut. He furrowed his brow but did it anyway. Hailigh sprayed him with something sweet, and he coughed. It was too much, but it covered up the scent of mota. Cash traded his worn sneakers for his new rain boots.

Once Hailigh and he made it to their stop, they ran off the bus before Don Mincho could ask them anything. Cash felt stones in his stomach on his walk home. The Elders usually never left Primavera unless there was something they were looking into.

When Cash got home, his mother was in the living room with her feet on the couch, listening to the news.

“Hi, Mamá.”

“Sit,” she said and pulled out a couple of pages from the pocket of her sunflower apron. Cash sat down, and his mother asked him about two letters from his school that he had forgotten to throw out. “When were you going to tell me about the money?”

Cash shrugged. “I don’t know. I wanted to take care of everything myself. You deal with a lot, and I knew you wouldn’t or couldn’t help me this time. I mean, you chose Salma over me. Which I get, okay?”

“Cash, what are you really doing? Where do you keep going?”

“Different places.” Cash scooted away from his mother. “I don’t like it here at home,” he said, trying to move the conversation to a more comfortable place. “My silly little trip money, as you said, was my way out. I don’t want to be here forever and only ever be a breadwinner. I don’t want to work myself to death like Papá. We’ll just end up the same: poor, with no indoor showers, living in what feels like a sardine can. And we’ll miss out on more of all the new stuff, like washing machines and skyscrapers and just things that are normal, because some old people care more about their ridiculous stay-in-the-box-for-your-safety rules and the sanctity of the old ways.”

“Cash, the rules are for protection. The Elders established everything for our good.”

“Who are they protecting? What good have the rules or anything The Elders said brought you? The rules wash everybody out. Papá wanted to leave. You know he wanted to go, and he asked you all the time to do something else, to go somewhere else, but you didn’t budge. He could still be alive if…I don’t know. Maybe he would’ve been fine if he hadn’t always been busy trying to revive the tortilleria or trying to please you.”

“Don’t do that to me. Don’t you blame me. I loved him just as much as you. He did what was best.”

“I’m not saying you killed him. I’m saying the rules did.”

“No one asked him to work for as long as he did. Do you think I didn’t warn him?”

“But he had to sustain all of us. Admit it. Admit that the rules are at least partly to blame here. Abuelo died, and he left you that forsaken business, and then Abuela gave it to Papá, not you. Now the only reason you have it is because Papá died. Don’t you get it? Don’t you see it?”

“Don’t treat me like I can’t understand. I demand your respect. I am your mother!”

“And I am the one who inherits all of this when you’re gone, and I don’t want it!”

“You don’t see what you have.”

“I guess I don’t.” Cash crossed his arms over his chest. “But you know what? I can tell that something is wrong here. Hailigh can’t be anything more than a kindergarten teacher, and she has the same amount of school as Nathanael and me. Her family pays exactly like me, and she won’t get to do what she loves. Careena’s father has no expectations of her. You want Salma to do more, but guess what? She’s busy thinking about getting married. It’s a school thing, but she shouldn’t even worry about that.”

His mother laughed. “Salma is not getting married right now. I wouldn’t allow it.”

“Why is that funny to you?”

“Cash, you are a man. It shouldn’t concern you what Salma thinks about that. It’s normal for her age. I spent time thinking about who I would marry and about my wedding, and I was younger than her.”

“That’s not normal, though. I don’t know how you can claim to want more for Salma but you’re okay that she’s trying to figure out something made for adults.”

“She has time to find a husband and do more. Why are you so worked up about this?”

Without thinking Cash said, “I don’t want her to end up like you.”

Cash’s mother was quiet. “There is nothing shameful about me.”

“I-I didn’t mean it like that.”

“You did.” His mother stared at him. Where had she gone wrong? Had she not loved him enough? Had she not provided for him? Since when had he looked down on her?

“Mamá, I didn’t mean—” Cash took a moment. “Are you happy?”

Aurélie blinked. The last person to ask her that was Fausto. “What does that have to do with your disrespect? Of course I’m not happy right now.”

“I’m talking about your life. Are you happy with your life?”

“Yes,” Aurélie said without much thought. “I’m alive, I have a roof over my head, there’s food in the kitchen, you and Salma are fine. Why wouldn’t I be happy with my life?”

Cash didn’t pry again. He would clearly get nowhere with his mother. “I’m glad you’re happy, but I want more. I thought you wanted that for me, too. I mean, after Papá you said things wouldn’t be that different for me, but they are. There’s this pressure to pick up where he left off.” Cash looked at his mother. “I don’t know how Papá did it to pull us through, but we’re not making it through anything right now. I mean, isn’t that why you take from me? You can’t handle taking his place.”

“I am doing what I can.”

“Well, so am I, but it’s not enough. I don’t know if there’s anything or anyone to really blame, but you can’t keep coming after me for helping. It shouldn’t matter to you how I do it. I’m supposed to do it. Isn’t that enough?”

“I can’t be proud of you if you’re doing something wrong.”

“How do you know I’m doing something wrong? I’m trying to help.”

“I don’t want the help that comes from whatever you do now.”

“Stop lying. It’s not even about wanting it, you need me.”

“No sos nada más que un mocoso.”

“Bueno.” Cash shrugged and went to his room.

There was nothing more to talk about.

Aurélie watched Cash walk off. She felt afraid. There was something dangerous about him.

Cash piled up his clothes in the closet and then pulled out his pajamas. He needed a shower. When he turned on the water outside, it was freezing. He gritted his teeth. How had their ration of hot water been used up so quickly? Cash had paid for it himself a week ago.

When he went back into the house, his mother was gone. Salma was in the living room instead.

“Where’d she go?” Cash asked.

“I don’t know. She didn’t tell me.”

Cash sat down and dried his hair.

“What do you do?”

“With my hair?”

“Stop it. No one is here.”

“I promise that it is so much better that you don’t know, Salmita.”

“Is it that bad?”

“If I get caught.”

“Oh.”

“Yeah.”

“Is that why sometimes your room smells weird?”

Cash only looked at his sister.

“You shouldn’t do it anymore.”

“I know.”

“I don’t think Papá would be very happy if he knew what you were doing.”

“If Papá were here I know I wouldn’t be doing it. He could’ve definitely convinced Darlin not to fire me, or at least he would’ve said something to dismiss her because he was more important than her.” Cash crossed his arms. “Did you know Mamá didn’t do anything when I got fired? I mean, she got mad at me, but she could’ve said something.” Cash shrugged. “I don’t know. Maybe she just didn’t think it was important to defend me.”

“Mamá is just soft. You know she likes to keep the rules as much as she can. She probably felt like she couldn’t talk with Darlin.”

“Doesn’t matter now, I guess.”

“Sorry.”

“It’s okay.” Cash hugged Salma and kissed the top of her head. “I love you, Salmita.”

“I love you too, Pisto.”

“I’m going to bed. Don’t worry about…anything, okay? Definitely don’t worry about guys more than you need or want to.”

Salma giggled. “Okay.”

Cash went to his room. He didn’t remember if he had left the door open or not when he went out for his shower. He shut the door behind him.

The next morning, Cash’s mother shook him awake. “Mijo, I need you to pick up the bread today.”

“I went last week,” Cash said and yawned.

“Can you do something without fighting me?”

“Yeah, I don’t wanna fight.” Cash stood up and shoved his arms into a jean jacket and put on a pair of sweats.

As Cash arrived at the bakery to pick up the bread for the week, he saw Ignacio outside typing slowly into a gray flip phone. Cash imagined it would take him hours for one message since he had such big, meaty hands. Everything about Ignacio was big. His frame, his forehead, his feet. Cash felt bad for his mother.

Cash took a deep breath before walking into the bakery and tried to convince himself it was just a coincidence that Ignacio was there. He usually picked random corners of the town to stand in anyway.