WHY WE CAN'T DISCERN GOD ? Today is a world full of development in fields of Science and Technology by talented and artistic people . Different types of people live in this world. All of them, directly or indirectly have inbuild talents by creative God.

A few of them are atheistic while others are theistic. But all humans are the creation of almighty God. People worship God for their good and request God to keep them fit and healthy and to bless them . But they donot worship God with full concentration and attachment. Hindus worship their God in temples, Muslims worship their God in Mosques, Sikhs worship their God in Gurdwaras while Christians worship their God in Churches. But a very few people are able to find God. This is due to the concentration and love with God and full faith in God . Many people when go to their worship place , they keep on watching their surroundings and other people rather than God . They pay a very few time praying God. Some of them on sitting for long time in worship centre , get bored and to overcome it they use smartphones to chat , watch videos , play games , phone call their relatives , disturb others who are wholeheartedly worshiping God and conversate with other people around them . If they pay attention towards God and pray them honestly, they will definitely find God. Children in worship places try learn everything they watch around them and if adults do these things , this will have bad effect on young generation too . Children , if doing something wrong in worship centres is not their mistakes as they are immature but the mistake of their parents. Parents are their future maker and must do best they can in front of them and in real life also as a child will follow characteristics of their parents only. While taking holy offerings ( prasada ) or blessings from the priests or food used as religious offerings the devotees often show their greed and want more quantity of blessings in form of ambrosia. This all is observed and noted as a record by God. Not even the mistakes of devotees but the priests also do many mistakes in those religious places. Priest, now a days, are indulged in wrong activities . They show very less attention to the God and devotees and their concentration is on what a devotee offer to God and its quantity and priest show their greed and cleverness in it. Priests try to do brainwash of the devotees and this too is under the supervision of almighty God and provide the prasada/blessings depending on the quantity and quality of the thing or amount or money a person gives to the God . A priest must be an ideal ,good intelligent and calm hearted religious person who should never do any discrimination based on caste, creed, color or gender. A mind full of purity and good thoughts is necessary condition to find God. God never wants amount or quantity or quality of thing and not even the thing , but God only wants the wholehearted attention and attachment of the devotees to him. He wants nothing but the faith of a devotee and God is ready to give everything good, a devotee wants or wishes to get as God is the creator of this world. God always exists within the heart of everyone . If a pure mind of a noble person with full concentration, when tries to find God, just by closing eyes is guranteed to get God's visit. Moreover, now a days , people are keeping copy of pictures or God's statue at their homes. These pictures or statues are produced in bulk by the painters/artists or idolist/sculptor . According to me ,this must not be done . As people produce various copies of God's pictures or statues and they are doing this just for their business. Except religious places, people are keeping the copy of God at their home, office , cars, using pictures of God in bracelets and necklaces . With this the value and purity of worship places are decreasing day by day . People carelessly keep God's pic anywhere and show very less respect to it . Many times , the industry where these sculpture or pictures are printed in bulk , they throw them in bundle or box from here to there and many of the prints tear off and statues are broken without considering them as a piece of worship and just try to gain maximum profits only by any means. But if on the same place , when God's statue is kept in a pure religious place, it will have considerable position and will be given great respect and faith. For example -: If a particular thing is present in large quantity, then people become unaware of it and they can use in whatever way they want and use it carelessly considering that if some quantity is used by a person then it will not affect the rest large quantity and waste it recklessly. On the other hand, if that particular this is present only in small amounts then people pay more attention to it and it become valuable for them and they take care of it very well considering that if people waste it they will not get if back easily again . That's why for having great value of God's statues/pics , the quantity of copies must be less. Moreover, in olden times people keep alot of cleanliness and purity in God's home by keeping footwear far away from religious place but now it's not the same rule. But people have now become very careless and pureless, as they keep their footwear infact anywhere . Today is a time when people their self are making their own rules and keeping footwear wherever they want and even so near the worship place. That's the reason why people are unable to find God and a few of calm hearted find God in today's world after alot of true worship.

0 Comments

Make America A Turnkey AgainAfter a short ferry ride from Seattle across Puget Sound I can hear in my mind the echoes of "send them back" and "build that wall." I am at the Japanese Exclusion Memorial on Bainbridge Island.

In March of 1942 american soldiers with rifles and bayonets herded 250 Japanese men, women, and children farmers aboard a boat to begin their trip to concentration camps in Idaho and California. They were allowed only what they could carry and had been given only 6 days notice. The Japanese had no idea of where they were going nor for how long. Many never returned, their land having been stolen by the vultures that had lobbied for their exclusion. It was not unlike today's desecration of The Bears Ears and other preserved lands handed over to big money donors so that job numbers will not reflect their natural state and hinder a re-election. However, with the help and support of the people that live here, some Japanese were able to make it back and start over. This memorial is a credit as well to their former neighbors who lived here and loved them. How different it is here than what they say is now most of this country. To me there is little wonder that most flights would fly over such bounty hunters and profiteers. To the tune of some lilly white christian hymn, it is also little wonder that what we see is again the forced degradation and removal of those who might have a dime to fall into wanting hands. I suppose many of those dimes will tinkle into the tithe jar as those aforementioned hymns are heralded. Afterwards, consciences and guilt salved, all good patriots will head to their afternoon barbeques. Thank God for this place of remembrance and those who keep it. It is here among the evergreen and Northwest fauna of a Puget Sound inlet that only by recall can the glitz and glamor of a hog mouthed conductor slopping his sucklings be heard. Very wooded, with a record of all those violated, the memorial is quiet.

CORONAVIRUS UPDATE - Early stage Someone stole the tip box at the Starbucks. Now we are being asked to donate to replace those tips. Did the thief need it more than the baristas? I heard about it on Nextdoor.

There is controversy between the board at our homeowner’s association and one of the homeowners. This is not the first incident. Three emails update me. There must be more time to write because of the quarantine. Outside my window, shimmering in the backlighting from the sun, a tiny spider is moving on its web looking for even smaller prey. It is oblivious to the virus. The virus is oblivious to the spider – it is much, much smaller than the spider’s prey. I hear the echo from the tv in the other room; we are on the same channel. News about Covid-19. What causes the delay? I calculated it is only .02 seconds away for the sound. Don’t the WiFi and Cable and satellite move at the speed of light? Where are the delays getting into the system, I have time to worry about those issues, thanks to shelter in place? So many people walk past my window – some I’ve never seen before. I should meet them – but maintain social distance. I’ve never liked shaking hands and despised hugging – I love it now, the new rules. My hermit inner self is in heaven. This can go on for me. We sneak out. We plan our outings for maximum joy. We take our sandwiches from Arby’s drive through to the park – it’s our new normal date night. We plan for a trip to buy groceries like it was a world tour. I look up the numbers on-line. Can I see a flattening of the curve? Not yet, but I know it is hidden somewhere in the data I have access to, or maybe they aren’t releasing all of the numbers, like the Chinese. There are rumors – urns at Wuhan – great significance, we went to Wuhan. Malaria meds work! I’ve taken them on trips to dangerous places on holidays and in VN – there were greater dangers there. People die from aquarium cleaner or rubbing alcohol. I get emails from my doctor, my gym, my local theatre, Panera, Bevmo – think I’ll take them up on the free pick-up on the sidewalk offer, my church, everyone wants to tell me what they are doing and what I must do. The US has overtaken China in number of cases. New Orleans, Chicago and Detroit are trying to surpass New York, I doubt that they can do it. Sports have been cancelled – wonder if I can get some kind of bet on that spider I saw. Results of tests are now available in 15 minutes! Some of them have accurate results; I almost wish I had some symptoms so I could get one. It’s named for a beer brand, well not really – sales of Cerveza Corona have fallen precipitously. Last time we were officially out, three weeks ago, I jokingly ordered a Corona from the bar tender, we laughed. He filed for Unemployment on Wednesday. I’m wasting time, I’ve got to do more. Motivate, motivate, motivate. Is this a waste of time? I spend time on-line. It’s comforting, it’s terrifying, my Wi-Fi becomes intermittent; that is really terrifying. I’m walking for exercise again. Trying to preserve my feet from the ravages of old age and a previous injury. I have named my walking routes – today I did Via Rancho Parkway, Yesterday we did Kay-2 – that’s with Blacks Hill, Kay-1 skips Blacks hill. The fourth route is Long-Steep, I’m saving it for tomorrow. Round trip to Target 6500 steps! Includes shopping. I take a shower every other day now . I skipped one day but couldn’t smell myself. Alert! Alert! Loss of sense of smell and taste are symptoms! I can smell other things. False alert. I gained three pounds one day - my scale is no longer my friend can a handful of chips be to blame? I have a target, a range of acceptable weight - fat? this isn’t within my acceptable range. It took three days of starvation to get rid of it – just not fair. When this is over, and it will be over, I’ll look back on the things I didn’t do. I look out the window again, I wonder whether the spider will catch his breakfast before he becomes someone else’s meal - a difficult way to move up the food chain. Corona Virus Update – late stage. Boring. Lois Greene Stone, writer and poet, has been syndicated worldwide. Poetry and personal essays have been included in hard & softcover book anthologies. Collections of her personal items/ photos/ memorabilia are in major museums including twelve different divisions of The Smithsonian. The Smithsonian selected her photo to represent all teens from a specific decade. Masked MessagingYou won a prize: a trip to London! Oh my gosh; you entered that contest ages and ages ago, and the award just came through. How totally great. Must be claimed how? Phone is just fine to get information? But, you say, the call is ‘outsourced’ and you can’t quite understand the speaker’s accent? Well, figure it out! This is just sensational news.

Details: travel must start by end of this month or prize voided. Okay. Get hold of the airlines! Hm, to get to London requires plane changes from your town just to get to the city that goes across the Atlantic Ocean. The state borders are restricting incoming traffic. Geez. Find another route. Maybe you can drive across state lines to get to the air-field. Yeah, the drive may take a couple of days but this trip, all expenses paid, is your ‘dream come true’. What did the plane reservation’s operator say? London will not accept admission of foreign travelers yet? Can’t be. Well, fly to France or ‘whatever’ and drive to London. Oh. That means you have to pay airfare. Didn’t think of that problem. Can’t this prize be extended to when you can enter England? Isn’t there a ‘small print’ for this whole thing because of the stupid virus? Yeah, The virus isn’t stupid, just the people who think nothing can happen specifically to them are stupid. Of course I prefer ‘gone viral’ to mean what it is supposed to mean: everyone everywhere can see what’s been posted online! That’s the viral I like. So how’d they come up with the word ‘virus’ to indicate something else? We just have to figure out how you can have your all-expenses paid trip to “London Bridge is falling down, falling down, falling down; London Bridge is falling down, my fair lady.” Of course I played that game in the elementary school yard during recess. Didn’t everybody? No. I never thought it had meaning. Has to do with repairing the structure? You’re kidding. A nursery rhyme is, well, a nursery rhyme. Little children don’t even know what a bridge is! “Ring around the Rosie” means what? You definitely are not serious. The Black Death. The rosy rash showed you had the plague, and the posies smelled over the scent of decaying flesh. Yuk. Now you want to ruin “Mary, Mary Quite Contrary” with the person being Henry VIII’s daughter and her brother Edward VI, and she couldn’t reverse ecclesiastical changes! Stop. I like the sing-song nursery rhymes and want to pretend each is about nothing. How can I sing them out loud ever again now that you’ve put these images in my head. All right. Enter another contest like this, and hope, if you do win it in about five years as it seems this one took almost that long, it’ll be like ‘ring around the rosie’ Black Plague and, back in the 14th century, it took four years of what we now call safe-distancing and it went away. Lois Greene Stone, writer and poet, has been syndicated worldwide. Poetry and personal essays have been included in hard & softcover book anthologies. Collections of her personal items/ photos/ memorabilia are in major museums including twelve different divisions of The Smithsonian. The Smithsonian selected her photo to represent all teens from a specific decade. like a penny I'm grown up. I really am 'mature', educated, worldly, but hardly sophisticated, which has little to do with getting older anyway. Well, so you can chuckle at how I can still blurt-out thoughts, I've got to give you a glimpse into a specific childhood event. Here goes:

I stood in the dinette facing my older sister. While she played with the ridges around her ten-cent coin, I insisted she couldn't have TWO of my nickels for just ONE of her dimes; two is more than one no matter what she said. My father attempted to explain that a dime was equal to two nickels; I didn't believe him. My smooth-edged circles were larger and had more designs on them. No one could fool me; I was six and smart. Screaming and calling me stupid, my nine year old sister assured me there was no trick to the transaction. I stubbornly stated that if they were the same, then I'd keep my two and she could keep her one. I knew I could outshout, outstare, outanything anyone. Stubborn was good. Grandpa tried to give me a funny coin once...to save. It said "Union Forever" and he called it a Civil War token. I told him to give it to my sister 'cause it wasn't real money. See. I was smart. Oh. And I remember Grandma trying to test me when she dropped a huge, heavy thing on my dresser. She called it a silver dollar. Who was she fooling? Dollars are made out of paper! I learned about money in school. First 'money' was oxen and cows since everyone needed something to pull a plow, give milk, haul a cart, be skinned for shoes and clothes. Then the teacher said that animals were too big to carry around so money had to be easy to carry and not spoil. So, small metal chips got stamped with something to show where they were made; yeah, art stuff. Good so far? Well, a zillion years ago in 1652, in Boston, Massachusetts, pictures of trees were put on our money and a man named John Hull gave his daughter her weight in coins as a wedding gift. Really! She got ten thousand Pine Tree shillings, but I couldn't remember, at the time, what a shilling meant so I didn't know if she had been fat or skinny. A metal bank from the World's Fair, shaped like a trylon and perisphere, had a coin slot that fit only pennies. Pennies were nice. I liked the color. When this bank filled, and I'd stabbed my hand on the trylon's sharp point hundreds of times, I sorted my cents and tried to have one Lincoln dated year by year. I hoped no one dropped those old Indian pennies in my bank; I only wanted Lincoln. He was a President of the United States. I learned that in school, also. Oh, I only kept the shiny Lincoln's if more than one had the same date. Bet you didn't think when I was a little kid that I knew names of presidents or how to read coin numbers like 1914, 1915, 1916 and more. Mommy had told me about mint marks but I couldn't imagine how mint leaves we put in tea could mark my pennies. Lincoln pennies spelled out 'one cent' on the back. That sure was sensible. My Jefferson nickel had his house on the 'tails' side when I flipped a coin. How could anyone from another country know that coin was a nickel when it didn't say so in big print! I was never going to save those. And Lincoln was in pictures all over school, well, wherever Washington wasn't. Grown up. With poise and intelligent awareness acquired with aging, I attended an exhibit of original photographic masterpieces. In The International Museum of Photography, I stared at real, not prints; some were even signed. Seeing the original "The Migrant Mother" was stirring. Famous names like Daugerre, Man Ray, Bruehl, made me search my learnings for each technique that separated them as artists. In open spots, free from assembled viewers, I moved not following sequenced dates of the display. A picture of once movie-actress Marlene Dietrich bothered me; I didn't like her eyebrows or position of her hand. I decided that the artist, however, intended to do something to cause a viewer to both remember her and his craft. I walked quietly taking in these treasures with adult fascination. When I got to a photograph of Lincoln, I forgot I was in a place of silence, as museums always are, so, quite loud and with a girlish giggle, I exclaimed "He looks just like the penny." May 1995 Rochester Shorts

WIDOWS ARE NOT BEGGARSI have been studying my mother's life after the death of my father in 2003. She has been strong woman, brave and a fighter. She doesn't give up easily when it comes to her goals. She doesn't complain no matter what's at stake. Sometimes, I wonder how she manages to put on a smiling face every day, how she manages to put on a bold face everyday no matter the circumstances that come on her way; how she has been able to train us to this moment. I wonder how she reacts whenever she misses my father. She must have missed her husband of many years many times but who would she complain to? Her children? God? I don't really know how she overcomes all these things but I believe that widows are strong people and in whatever way we think we can help them, we should. We should try to sustain those smiles on their faces and give them hope of tomorrow. They say, a husband is a cover for her wife and when a woman loses her husband, she loses part of herself and that is true. Mother has been my number one fans and a role model. Some years back, I stormed into her room to see mother watching the photographs of father in between smile and tears — her fears increased the tempo of her heart beats and the atmosphere was tensed. She was not aware that someone was inside the room. I stood there in tears, too. I tried not to break into her thought as I made for the door and left. I’d once been told that if a woman wanted something she did not have, no matter how elusive that thing was, if her feet do not restrain her from chasing it, she would eventually grab it but not when the love of their life is gone to return no more. Some of these women maybe in their thirties or late forties but refused to remarry after the death of their husbands. Some of them did this not because they were strong enough to be alone but because they were afraid that the new husband might not accept their children. He might not like or love them just like her or see them as his own children. Even if he does, his family members may not want them and so, they decide to remain single for their children's interest and some, may decide not to remarry because of the love they have for their children. They have to stay and train up their children. Give them a better life and future as they desire. Some may not because of the love for their dead husbands. Widows are strong people so as widowers who never remarried. However, these women should not been seen as beggars when they come to you for help. Help them in the little way you can. Put a smile on their faces. They are not beggars but victims of circumstances. Who fate seized their entities in way to deny them of love and affection. Show them some love if you come across them. Give them gifts no matter how little it is, they will appreciate it. I'm always happy to see churches set aside one Sunday to celebrate widows and widowers. They present gifts to them and pray for them. This, in some ways, lifts their spirits and help them realise that some people still care about them and their well being. If your mother is a widow or your father is a widower, please, don't provoke him or her. Don't make her think about your father and dont make him think about your mother. Help them in a little way you can. It does not matter how small it may look but just help. There is this woman in my street, her husband was a soldier. She was living happily with him and their three children; one boy, two girls, until Boko Haram came. Until bombing started. Until Nigeria started taking much interest in Boko Haram than her Army. Her husband was among the people sent to Sambisa. He went and never returned. Nobody knows anything about him again till now. We don't know if he was killed or wounded. Nobody knows if he's alive or not but we have all concluded that he's dead because he has been missing for long. Now, the woman is a widow catering for three wonderful children, a job she once shared with her husband. Some weeks ago before she packed out of our street, some people came and offered her presents. They prayed for her and promised to come back again. Later, a friend of her told me how happy she was when those people presented those gifts to her. According to her, she had nothing to cook for her children in the past Christmas before those people came. She had planned that she would take them to their father's sister place for the Christmas since nothing was at home. But miracle happened and those people brought those items for her. Imagine how happy she would have been after they left. On 23 of December, 2019, we planned on visiting few of them I know around my house to give them some gifts but we failed because the money we were expecting didn't arrive. And some of our plans failed us, too. They failed us in many ways which I may not likely go into details for now. But my take here is that, always try as much as possible to leave on the faces of these widows and widowers because they need it from you. Help them in any way you can. FOR COURAGE, STEADFASTNESS AND EVERYTHING BEING A WIDOW BRINGSWhile growing up in Aba, there were many single mothers and fathers I knew in my street. And these single mothers and fathers have children. Some have six children and some seven and others, eight before the death of their spouse. You'll believe that no matter how good a mother is, it is not good for only her to train a child. And no matter how lovely a father is, it is not also good for only him to train his children. Some fathers are usually strict and hot while dealing with their children while some mothers are some how soft while training their children. However, if the two comes together to train up a child, the child will end up becoming normal to some extent. When a father becomes too hot or strict with his dealings, the softness of a mother turns his anger cold or some how soft to the children. Perhaps, that is how nature has made it to be; two hands in training and upbringing of a child. But in a situation where we have only a father or a mother, it becomes too hard for a single hand to train and care for a child.

In my church then, we have a special service every month for the widows and widowers in the church. This service usually take place every last Sunday of the month and my Pastor who was then working with one oil company in Port Harcourt had an account he set aside for these widows and widowers and he gave willing members who God had touched in their heart to donate as well for this course. In fact, the gate was widely opened in my church that some widows and widowers that were not the church members are allowed to come to that service. They were treated equally like the church members. And respected, too. So, a day before the service usually on Saturday, the pastor appoints some members of the church who go to the market to buy food stuffs ranging from bags of rice, Tin tomatoes, Maggi, fresh Fish, Vegetables and lots of other things. During this service, all the widows and widowers are called out on the church altar and prayed for. They are prayed for by the pastor and the church members along side their children. Later, the gifts are presented to them all. I was always fascinated by the smiles on their faces. By the expression on their faces and how they would walk majestically back to their seats. The pastor would always tell them to walk majestically to their seats and never allow anybody intimidate them because they were widows and widowers. They should not be ashamed of who they are and never get tired of disturbing God who would take care of them. I grew up loving these people. I grew up having a soft spot for them because of the courage and strength they exhibit. Because these people, are still happy after their misfortunes, they found reasons to moved on with their lives after the death of their spouses. They were not after how the storm of life is throwing them here and there, the tribulations of life may come in different forms but they were not moved by it. That has always been my happiness. No matter how ugly your mother is ( if there is anything like that), she is still your mother and there's nothing to equal her in anyway, same as your father. Aside from being strong people, these widows and widowers have something in common too, they are courageous and brave. You hardly see their tears in public. They have these characteristics of holding on for a very long time. They live a prayerful life. A life full of hope and faith. A grieving widow’s pain is unique and volatile. What encourages and uplifts one woman may be painfully unhelpful to another. Grief is like a virus that waxes and wanes with intensity. The Quest for survival has made many of us forget the smallest of all things which is very relevant to our neighbors. We have forgotten the significance abound in longing to help those who are in need. Perhaps the toiling and sweat of our daily activities have made us lose concentration of those who seek for our attention in our communities. I have come to understand that everything is not all about money. Sometimes when we don't have money, we should encourage and care for some people, it helps. The magnitude of what we have forgotten are those things hurting us some times and more and more are going right into the drain because some of us no longer cares. Maybe, you should in your spare time, think about these people logically. These people that some well fed neighbors have categorized as baggers because they seek for water to quench their taste. They are widows not baggers. They are not dogs you stone food at. Bedbug once told it children that they should endure that everybody would have a large lips. Nobody asks for death, it comes and takes when he needs a soul. Meanwhile, don't neglects these people. Don't allow them tear up when they remember their lost ones. Help them in whichever way you can. A grieving widow who lives alone may go several days without hearing another human voice, especially months after the initial funeral of her husband. Emails, text messages and letters are good; however, phone calls and visits may be better if you can create that time. While this may not seem like the most efficient use of your time, efficiency and effectiveness are sometimes mutually exclusive. Emotional mine fields such as these may require intimate knowledge of the bereaved and how they are taking the Lost of their lives ones. A close friend, relatives or neighbors might be better suited to visit a widow than some Pastors. Don’t confuse compassion for a church acquaintance with a call to take personal action. If you don’t know the widow well, allow one of her close friends to direct your efforts. It will ease out so many things when someone very close visits her. Cristina Deptula, writer and publisher of international literary magazine Synchronized Chaos (synchchaos.com) and a freelance journalist and literary publicist.

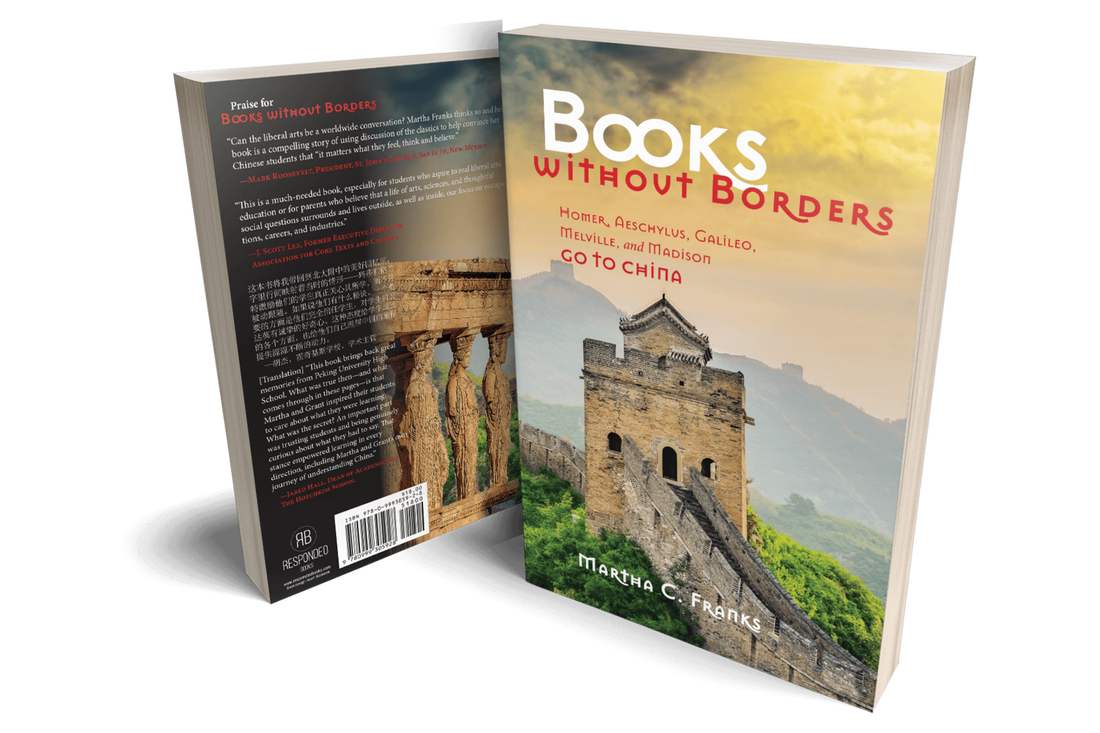

INTERVIEW WITH MARTHA FRANKSMartha Franks spent the academic years 2012-14 in Beijing, China, developing and teaching a liberal arts curriculum at the Affiliated High School of Peking University (BDFZ). She brought to that task her experience as a part-time faculty member at St. John's College in Santa Fe, New Mexico. At St. John's, and then at BDFZ, she taught the classics of Western literature through discussion classes. Both the books and the style of teaching were new experiences for her Chinese students.

["What is the best life?" I asked, the classic philosophical inquiry. After a silence, one of the students--I could not see who--whispered, "The best life is to be rich."] Ms. Franks has had a separate career as a lawyer. She began that career with a few years at a large Wall Street law firm, after which she moved to New Mexico, where she has practiced water law for thirty years. She offered a class in American Law to Chinese students. ["It's not true that everyone is created equal like this Declaration says!" objected some students strongly. Others were just as sure that the truth of this claim was self-evident.] Ms. Franks also has a degree in theology from the Virginia Theological Seminary in Alexandria, Virginia. In addition to her book about teaching in China, she has a number of publications in both water law and theology. She is a painter, having attended the Marchutz School of Art in Aix-en-Provence, France. Lots of different experiments in what is the best life. Books without Borders: Homer, Aeschylus, Galileo, Melville and Madison Go to China by Martha Clark Franks 246 pages Paperback $18.00 Also available as an ebook Nonfiction, Memoir, Cultural Studies Publication Date: May 30, 2019 Respondeo Publishing ISBN-13: 978-0999305928 Contact: [email protected] More info at: https://www.respondeobooks.com/new-products/books-without-borders You teach at a very unique institution here in the United States. What is the educational philosophy of St. John's College? St. John’s College believes that we learn by talking together about the great creative works of the human spirit. The college is committed to the idea that classic original texts offer foundational insights about ourselves and our society and that students should form their own opinions of these works rather than being told by textbooks and lectures what to think about them. St. John’s has only one program of teaching; that is, discussions about great works. Under this broad program, undergraduates concentrate on the great books of the Western world. There are two graduate programs at the College. One, the Graduate Institute of Liberal Arts, looks at the same works as the undergraduate program, while another, the Eastern Classics program, takes the St. John’s approach toward classics of China, India and Japan. The St. John’s College program grew from radical criticism of the structure of liberal arts education in the early 20th century. The concerns that the College sought to address then are perhaps even more relevant today, when liberal arts education is challenged by exclusively STEM-based or narrow vocational education. Could you describe classroom etiquette and culture in China vs the USA (what you've experienced and where you teach)? Chinese students were not used to talking in class. They had a hard time believing that I genuinely wanted to hear what they had to say. Although they did not complain, they also doubted that expressing their ideas would lead to learning. It took some time before they entered into conversation without being self-conscious. Once that began to happen, however, they were quick to feel the curiosity and joy of their minds at work, taking them places that they could only go on their own. It was lovely to see. American students sometimes come at conversation from the opposite direction. They are familiar with raising their voices but must get used to the skill of listening to responses and building on them. After a while together, though, I did not see a difference in the conversations that developed in China and America. What sorts of ancient Western concepts did the Chinese students relate to, and which were mystifying to them? The students related to all matters of our common humanity, which was wonderful for all of us. It was great to feel that we were people together, trying to figure out how to live in this bewildering world. We could converse and understand each other. Some of our cultural prejudices were different. In America, there is a saying “the squeaky wheel gets the grease.” In the East, there is a saying “it is the nail that sticks up that gets hammered.” So the students were more reluctant to talk than their American counterparts (although some of this was due to second language issues), and disliked disagreement more. Religion was mystifying to them. They had no experience of it and did not know how to understand what it was in the West. When we read the Iliad they wondered if the gods of Greece were what religion still looked like. When we tried to read some of the texts of early Christianity they were simply bewildered and did not talk at all. What would you say you learned from Chinese culture and history? What do they emphasize that the Western world could learn from? As I gave my Chinese students Western classics to read, I also read Eastern classics as a way of empathizing from the other direction with their exploration of an entirely different culture. The picture in China is complicated, in that Marxism is a Western idea, and the desire to catch up with the West technologically is a powerful force in China, which means that Western ideas can generate a mix of desire and resentment. Many of my students did not know very much about their own cultural past, although they were proud of China’s five thousand years of civilization. The chief thing that I learned, or at least meditated on a great deal, was this picture of Chinese identity arising somehow from those five thousand years, even though governments and cultural sensibilities evolved and changed enormously in that length of time. It is a vision of identity that has less to do with particular ideals and ideologies, and more to do with a sense of living within deep time. I also came to appreciate and admire the combination of delicacy and strength in Chinese art and poetry. Classic Eastern texts like The Dream of the Red Chamber are gentle and sensitive to a degree that a person can feel lost in fragile beauty. The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, by contrast, is a warrior tale of relentless war, although it too contains moments of gentleness and sensitivity. I think the West, and perhaps all of us humans, could spend more time seeing beauty. What makes a literary work a classic? Why should we still teach the traditional canon? What about efforts to update or diversify it? A classic work is one that can be read again and again and never be exhausted of meaning and engagement. As member of the faculty of St. John’s College, a school that reads great books as the center of the curriculum, I have read Homer and Plato and Augustine and Shakespeare many times. Every time I read these books I find more in them that speaks to my present life as well as to my mind and heart. We need to teach these books because of that experience of how inexhaustible they are. As I watch college students reading them, I am glad—sometimes thinking of my Chinese students—to offer them the proud, compelling gifts of their human heritage. Greatness is certainly not confined to any particular culture, gender or any such false separations of the human experience. Sadly, the practical reality of the dominating tendency of our species is that women and many cultures were not allowed to produce the works of profound beauty that we needed from them. When such works are found, either in the past or the present, they become part of the canon. What would a 'global literary canon' look like? Who would decide what's in the global canon, and how would they make those decisions? The experiment of St. John’s College’s great books program, which has been going on for almost eighty years, has shown that an education based on conversations around great works of the human spirit can open and free minds, as well as being amazingly fun. It’s a harder question to try to identify exactly which books belong on a great books list. A few are always at the center of a Western canon—Homer, Euclid, Plato, Shakespeare—but most of the rest have their advocates and opponents. Conversation about that list is always going on and the list changes with different sensibilities, especially as one comes to more recent works. It has been wonderful to be part of the evolution of the St. John’s list to include the voices of women and minorities speaking to the human experience from points of view that were for too long too often missing from the conversation. When a global list comes about the conversation will grow again. The dream is to include all points of view so that humanity is fully heard from. Do you feel that people, in China or in the West, are still influenced by our foundational books? Even people who have not read the traditional classics? Yes to both questions. Even when people are not aware of how these deep structures to their culture influence them, the influence is there. Part of the value of reading the canon is to notice those influences working. A reader discovers in their original form as new ideas things that the reader realizes s/he had previously unthinkingly accepted as if obviously true. From that changed relationship with these ideas, the ideas can be reassessed. The reader may continue to think them true, but now they feel true in a fuller, surer way. In my class on American law in China, for example, we discussed the line in the American Declaration of Independence that “All men are created equal. . . .” The conversation ranged fearlessly over questions of gender, creation and the definition of equality. By the end of that conversation there was both agreement and disagreement, but both were articulated and could be considered in the open. The conversation will undoubtedly continue for all of us. What surprised and impressed you the most about China’s foundational works? I believe that Chinese society has been influenced by its foundational books. Students are taught to read Tang era poetry and are aware, but often not really familiar with, classical authors such as Kongzi (Confucius) and Mengzi (Mencius). However, China’s relation to its own literary tradition is an especially interesting case because of the overlay of the Western ideology of Marxism. Nevertheless, as China grows cautiously away from a Marxist economy, it has been developing what it calls “socialism with Chinese characteristics.” Those “Chinese characteristics” are not defined but they must be related to China’s pride in its five-thousand-year history of civilization, a pride that is deeper than any political dogma. Confucius has been increasingly re-established and celebrated in China, with his emphasis on ritual and humaneness. No doubt there will be hesitations along the way, but I believe that China will find its way into a modern, uniquely Chinese re-assertion of Confucian humaneness that will be in conversation with the Western notion of the humanities. It’s hard to say which culture is more influenced by its foundational works—that would be a lifetime’s study. If there is truth in the sketch I have offered here, that the canon of Western culture has developed into a focus on freedom, whereas Eastern culture has more often emphasized virtue and order, then both are pointing to fundamental human impulses that will continue to converse in all and each of us. What surprised me most in studying Eastern classics was recognizing this struggle that I had seen in the Western canon too between the desire and need for freedom, especially in the mind, and the necessity of discipline. It’s a human problem and we can help each other with it. That’s interesting, the perennial conflict between liberty and social order. How can conversations about classic works help us understand the roots of these kinds of present-day social issues? Attitudes and ideas fill the air we breathe, whether we are aware of them or not. For example, in America it seems obvious that the goal of society is to promote freedom. That attitude didn’t come from nowhere. It was proposed and articulated by particular people—John Stuart Mill, for one – who were contributing new ideas to a conversation about human purposes. For many centuries the participants in that conversation had seemed to agree that the goal of society was not to promote freedom but to uphold virtue and order even at the cost of freedom. We understand our present debates between liberals and conservatives if we have in mind the earlier conversation that shaped our shared traditions. Only then can we see what has been at stake in that clash of ideas and form a personal opinion about why we have chosen as we have. In cultures with different traditional conversations the focus on freedom that Americans take for granted looks different and can seem dangerous, even though the impulse toward freedom is something that is present in every human community and is not strange to Eastern thinkers. That situation is another reason why working to create a single, global conversation is so important. Attitudes and ideas that have been unconsciously absorbed and never examined can result in misunderstandings and distrust, whereas listening to each other’s conversations can show how the same human problems are always present. We must work to understand our own foundational ideas better, which will make it possible to feel the human reasonableness of another culture’s foundational ideas. Would you recommend teaching abroad in China? Do you feel that you grew through the experience? Yes again. Physical distance and the change of culture has a similar effect of allowing a person to look carefully at themselves and notice the things that they might previously have accepted unthinkingly. Reading great books is like traveling to the past, while traveling more literally provides a different kind of dislocation. Both are valuable to understanding who you are. Could you teach this way in the US? How much freedom do teachers have in other countries to create and influence curriculum? I was very lucky to have gone to China exactly when I did, when there was a flowering of experiments in progressive education. We had a good deal of freedom to create a curriculum. Some of those experiments are still going on, but China, as I describe in my book, is conflicted about the value of a liberal arts education. For decades, China concentrated on a STEM education, that is, one focused on math and science. Recently that has changed, as some have argued that the liberal arts should be taught as a source of creativity for China. Others, however, are against that change, concerned that the liberal arts are foolish luxuries and can also be subversive politically. The same conflict is going on in the United States, as many liberal arts colleges are struggling. It would be a shame if liberal arts declines in the United States just as it arises in China. For me, the liberal arts display the full range of what it is to be human. We all need that. If you could do the semester in China over again, what would you change? Not much. I might have a few different choices of exactly what books to read. The only real difference is that, if I were to return, I would be able to show more confidence that an approach that I loved myself was something that Chinese students would also love. Conversation is a human thing. It’s how many of us learn best. It was wonderful to be part of a conversation that, while sometimes surprising because of the different backgrounds of the participants, was like all serious conversation in the delight of exchanging ideas.

Letter from Sicily |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed