|

Cristina Deptula, writer and publisher of international literary magazine Synchronized Chaos (synchchaos.com) and a freelance journalist and literary publicist.

INTERVIEW WITH MARTHA FRANKSMartha Franks spent the academic years 2012-14 in Beijing, China, developing and teaching a liberal arts curriculum at the Affiliated High School of Peking University (BDFZ). She brought to that task her experience as a part-time faculty member at St. John's College in Santa Fe, New Mexico. At St. John's, and then at BDFZ, she taught the classics of Western literature through discussion classes. Both the books and the style of teaching were new experiences for her Chinese students.

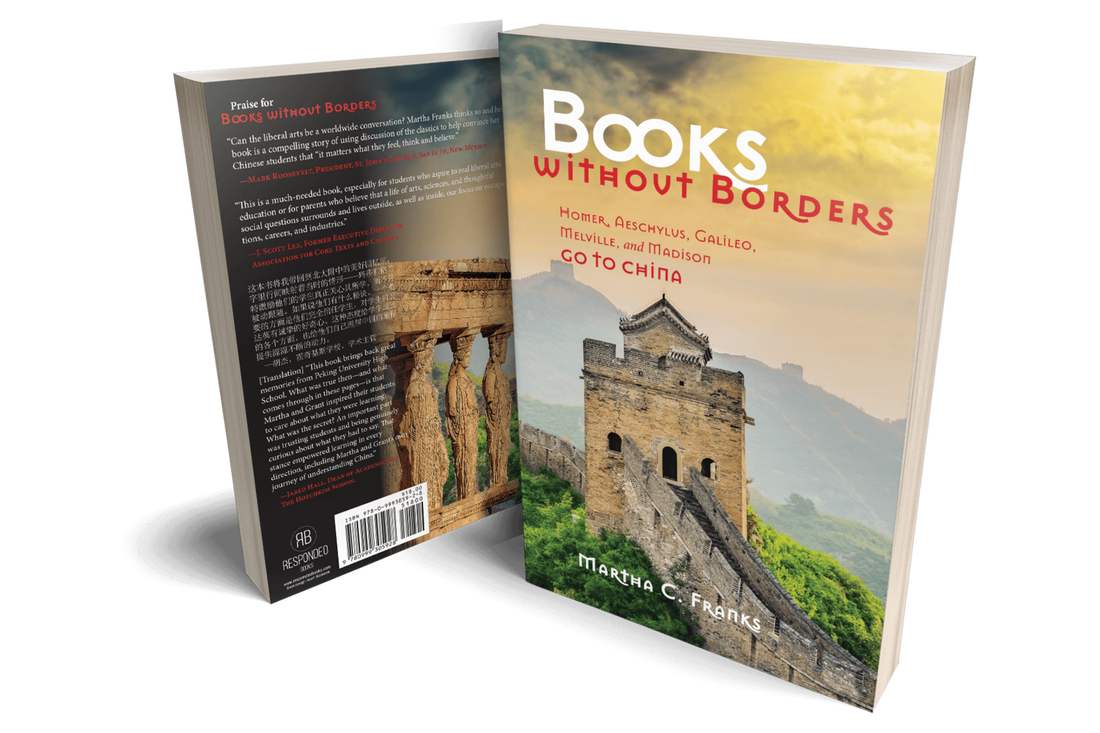

["What is the best life?" I asked, the classic philosophical inquiry. After a silence, one of the students--I could not see who--whispered, "The best life is to be rich."] Ms. Franks has had a separate career as a lawyer. She began that career with a few years at a large Wall Street law firm, after which she moved to New Mexico, where she has practiced water law for thirty years. She offered a class in American Law to Chinese students. ["It's not true that everyone is created equal like this Declaration says!" objected some students strongly. Others were just as sure that the truth of this claim was self-evident.] Ms. Franks also has a degree in theology from the Virginia Theological Seminary in Alexandria, Virginia. In addition to her book about teaching in China, she has a number of publications in both water law and theology. She is a painter, having attended the Marchutz School of Art in Aix-en-Provence, France. Lots of different experiments in what is the best life. Books without Borders: Homer, Aeschylus, Galileo, Melville and Madison Go to China by Martha Clark Franks 246 pages Paperback $18.00 Also available as an ebook Nonfiction, Memoir, Cultural Studies Publication Date: May 30, 2019 Respondeo Publishing ISBN-13: 978-0999305928 Contact: [email protected] More info at: https://www.respondeobooks.com/new-products/books-without-borders You teach at a very unique institution here in the United States. What is the educational philosophy of St. John's College? St. John’s College believes that we learn by talking together about the great creative works of the human spirit. The college is committed to the idea that classic original texts offer foundational insights about ourselves and our society and that students should form their own opinions of these works rather than being told by textbooks and lectures what to think about them. St. John’s has only one program of teaching; that is, discussions about great works. Under this broad program, undergraduates concentrate on the great books of the Western world. There are two graduate programs at the College. One, the Graduate Institute of Liberal Arts, looks at the same works as the undergraduate program, while another, the Eastern Classics program, takes the St. John’s approach toward classics of China, India and Japan. The St. John’s College program grew from radical criticism of the structure of liberal arts education in the early 20th century. The concerns that the College sought to address then are perhaps even more relevant today, when liberal arts education is challenged by exclusively STEM-based or narrow vocational education. Could you describe classroom etiquette and culture in China vs the USA (what you've experienced and where you teach)? Chinese students were not used to talking in class. They had a hard time believing that I genuinely wanted to hear what they had to say. Although they did not complain, they also doubted that expressing their ideas would lead to learning. It took some time before they entered into conversation without being self-conscious. Once that began to happen, however, they were quick to feel the curiosity and joy of their minds at work, taking them places that they could only go on their own. It was lovely to see. American students sometimes come at conversation from the opposite direction. They are familiar with raising their voices but must get used to the skill of listening to responses and building on them. After a while together, though, I did not see a difference in the conversations that developed in China and America. What sorts of ancient Western concepts did the Chinese students relate to, and which were mystifying to them? The students related to all matters of our common humanity, which was wonderful for all of us. It was great to feel that we were people together, trying to figure out how to live in this bewildering world. We could converse and understand each other. Some of our cultural prejudices were different. In America, there is a saying “the squeaky wheel gets the grease.” In the East, there is a saying “it is the nail that sticks up that gets hammered.” So the students were more reluctant to talk than their American counterparts (although some of this was due to second language issues), and disliked disagreement more. Religion was mystifying to them. They had no experience of it and did not know how to understand what it was in the West. When we read the Iliad they wondered if the gods of Greece were what religion still looked like. When we tried to read some of the texts of early Christianity they were simply bewildered and did not talk at all. What would you say you learned from Chinese culture and history? What do they emphasize that the Western world could learn from? As I gave my Chinese students Western classics to read, I also read Eastern classics as a way of empathizing from the other direction with their exploration of an entirely different culture. The picture in China is complicated, in that Marxism is a Western idea, and the desire to catch up with the West technologically is a powerful force in China, which means that Western ideas can generate a mix of desire and resentment. Many of my students did not know very much about their own cultural past, although they were proud of China’s five thousand years of civilization. The chief thing that I learned, or at least meditated on a great deal, was this picture of Chinese identity arising somehow from those five thousand years, even though governments and cultural sensibilities evolved and changed enormously in that length of time. It is a vision of identity that has less to do with particular ideals and ideologies, and more to do with a sense of living within deep time. I also came to appreciate and admire the combination of delicacy and strength in Chinese art and poetry. Classic Eastern texts like The Dream of the Red Chamber are gentle and sensitive to a degree that a person can feel lost in fragile beauty. The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, by contrast, is a warrior tale of relentless war, although it too contains moments of gentleness and sensitivity. I think the West, and perhaps all of us humans, could spend more time seeing beauty. What makes a literary work a classic? Why should we still teach the traditional canon? What about efforts to update or diversify it? A classic work is one that can be read again and again and never be exhausted of meaning and engagement. As member of the faculty of St. John’s College, a school that reads great books as the center of the curriculum, I have read Homer and Plato and Augustine and Shakespeare many times. Every time I read these books I find more in them that speaks to my present life as well as to my mind and heart. We need to teach these books because of that experience of how inexhaustible they are. As I watch college students reading them, I am glad—sometimes thinking of my Chinese students—to offer them the proud, compelling gifts of their human heritage. Greatness is certainly not confined to any particular culture, gender or any such false separations of the human experience. Sadly, the practical reality of the dominating tendency of our species is that women and many cultures were not allowed to produce the works of profound beauty that we needed from them. When such works are found, either in the past or the present, they become part of the canon. What would a 'global literary canon' look like? Who would decide what's in the global canon, and how would they make those decisions? The experiment of St. John’s College’s great books program, which has been going on for almost eighty years, has shown that an education based on conversations around great works of the human spirit can open and free minds, as well as being amazingly fun. It’s a harder question to try to identify exactly which books belong on a great books list. A few are always at the center of a Western canon—Homer, Euclid, Plato, Shakespeare—but most of the rest have their advocates and opponents. Conversation about that list is always going on and the list changes with different sensibilities, especially as one comes to more recent works. It has been wonderful to be part of the evolution of the St. John’s list to include the voices of women and minorities speaking to the human experience from points of view that were for too long too often missing from the conversation. When a global list comes about the conversation will grow again. The dream is to include all points of view so that humanity is fully heard from. Do you feel that people, in China or in the West, are still influenced by our foundational books? Even people who have not read the traditional classics? Yes to both questions. Even when people are not aware of how these deep structures to their culture influence them, the influence is there. Part of the value of reading the canon is to notice those influences working. A reader discovers in their original form as new ideas things that the reader realizes s/he had previously unthinkingly accepted as if obviously true. From that changed relationship with these ideas, the ideas can be reassessed. The reader may continue to think them true, but now they feel true in a fuller, surer way. In my class on American law in China, for example, we discussed the line in the American Declaration of Independence that “All men are created equal. . . .” The conversation ranged fearlessly over questions of gender, creation and the definition of equality. By the end of that conversation there was both agreement and disagreement, but both were articulated and could be considered in the open. The conversation will undoubtedly continue for all of us. What surprised and impressed you the most about China’s foundational works? I believe that Chinese society has been influenced by its foundational books. Students are taught to read Tang era poetry and are aware, but often not really familiar with, classical authors such as Kongzi (Confucius) and Mengzi (Mencius). However, China’s relation to its own literary tradition is an especially interesting case because of the overlay of the Western ideology of Marxism. Nevertheless, as China grows cautiously away from a Marxist economy, it has been developing what it calls “socialism with Chinese characteristics.” Those “Chinese characteristics” are not defined but they must be related to China’s pride in its five-thousand-year history of civilization, a pride that is deeper than any political dogma. Confucius has been increasingly re-established and celebrated in China, with his emphasis on ritual and humaneness. No doubt there will be hesitations along the way, but I believe that China will find its way into a modern, uniquely Chinese re-assertion of Confucian humaneness that will be in conversation with the Western notion of the humanities. It’s hard to say which culture is more influenced by its foundational works—that would be a lifetime’s study. If there is truth in the sketch I have offered here, that the canon of Western culture has developed into a focus on freedom, whereas Eastern culture has more often emphasized virtue and order, then both are pointing to fundamental human impulses that will continue to converse in all and each of us. What surprised me most in studying Eastern classics was recognizing this struggle that I had seen in the Western canon too between the desire and need for freedom, especially in the mind, and the necessity of discipline. It’s a human problem and we can help each other with it. That’s interesting, the perennial conflict between liberty and social order. How can conversations about classic works help us understand the roots of these kinds of present-day social issues? Attitudes and ideas fill the air we breathe, whether we are aware of them or not. For example, in America it seems obvious that the goal of society is to promote freedom. That attitude didn’t come from nowhere. It was proposed and articulated by particular people—John Stuart Mill, for one – who were contributing new ideas to a conversation about human purposes. For many centuries the participants in that conversation had seemed to agree that the goal of society was not to promote freedom but to uphold virtue and order even at the cost of freedom. We understand our present debates between liberals and conservatives if we have in mind the earlier conversation that shaped our shared traditions. Only then can we see what has been at stake in that clash of ideas and form a personal opinion about why we have chosen as we have. In cultures with different traditional conversations the focus on freedom that Americans take for granted looks different and can seem dangerous, even though the impulse toward freedom is something that is present in every human community and is not strange to Eastern thinkers. That situation is another reason why working to create a single, global conversation is so important. Attitudes and ideas that have been unconsciously absorbed and never examined can result in misunderstandings and distrust, whereas listening to each other’s conversations can show how the same human problems are always present. We must work to understand our own foundational ideas better, which will make it possible to feel the human reasonableness of another culture’s foundational ideas. Would you recommend teaching abroad in China? Do you feel that you grew through the experience? Yes again. Physical distance and the change of culture has a similar effect of allowing a person to look carefully at themselves and notice the things that they might previously have accepted unthinkingly. Reading great books is like traveling to the past, while traveling more literally provides a different kind of dislocation. Both are valuable to understanding who you are. Could you teach this way in the US? How much freedom do teachers have in other countries to create and influence curriculum? I was very lucky to have gone to China exactly when I did, when there was a flowering of experiments in progressive education. We had a good deal of freedom to create a curriculum. Some of those experiments are still going on, but China, as I describe in my book, is conflicted about the value of a liberal arts education. For decades, China concentrated on a STEM education, that is, one focused on math and science. Recently that has changed, as some have argued that the liberal arts should be taught as a source of creativity for China. Others, however, are against that change, concerned that the liberal arts are foolish luxuries and can also be subversive politically. The same conflict is going on in the United States, as many liberal arts colleges are struggling. It would be a shame if liberal arts declines in the United States just as it arises in China. For me, the liberal arts display the full range of what it is to be human. We all need that. If you could do the semester in China over again, what would you change? Not much. I might have a few different choices of exactly what books to read. The only real difference is that, if I were to return, I would be able to show more confidence that an approach that I loved myself was something that Chinese students would also love. Conversation is a human thing. It’s how many of us learn best. It was wonderful to be part of a conversation that, while sometimes surprising because of the different backgrounds of the participants, was like all serious conversation in the delight of exchanging ideas.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed