|

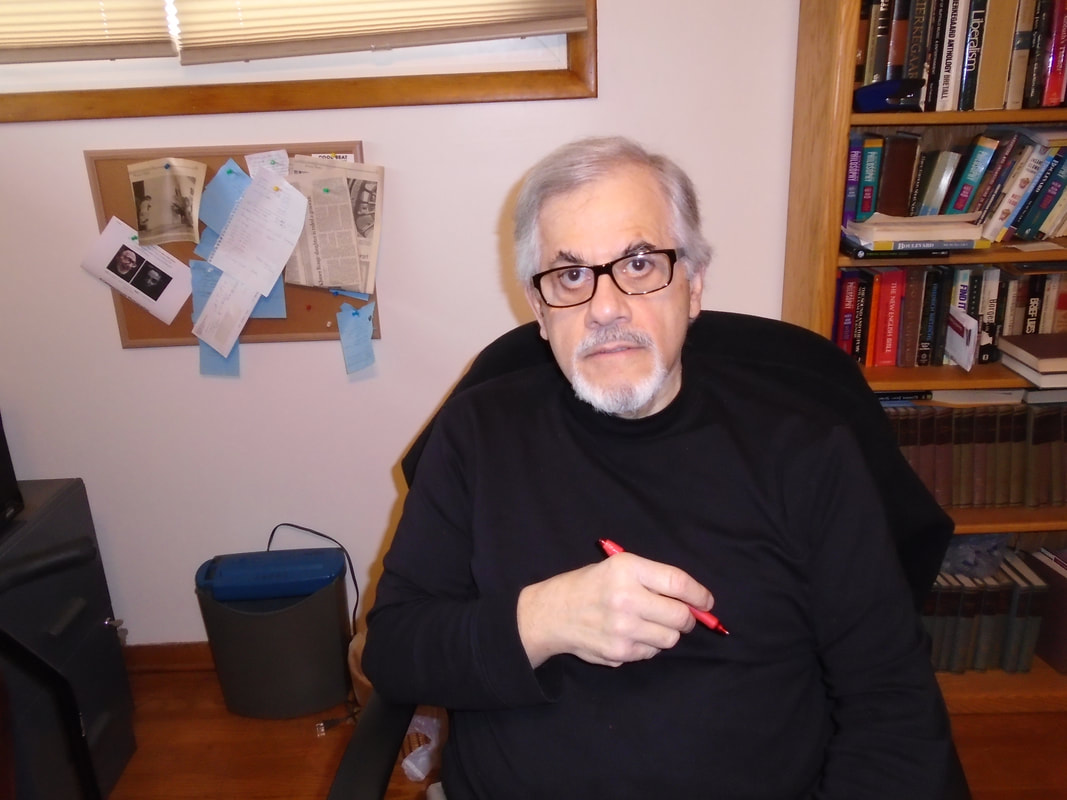

Robert P. Bishop, a former soldier and teacher, holds a Master’s in Biology and lives in Tucson, Arizona. He is the author of three novels and four short-story collections and has twice been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. His short fiction has appeared in Active Muse, Ariel Chart, Better Than Starbucks, Bright Flash Fiction Review, Clover and White, CommuterLit, Corner Bar Magazine, Fleas on the Dog, Ink Pantry, Literally Stories, The Literary Hatchet, Lunate Fiction, The Scarlet Leaf Review and elsewhere. A Home in the Country Claire watched the movers wheel her upright piano into the room with the ornate fireplace. She stood by the fireplace and twined her fingers together. Her lips trembled and a muscle twitched on the left side of her neck. One of the movers, the older of the two men, thought she might start crying. He had seen these kinds of moves before and suspected this marriage would not last. Claire looked at Lionel, her husband. “Do you think we did the proper thing?”

“Of course,” said Lionel, rising on his toes and spreading his arms wide. “Look at this house! It is magnificent, and there are no neighbors for miles around. It is a wonderful place to live, and not at all like London. I shall love it here.” He smiled at her from across the room. “We are so far from everything,” she protested. “I don’t know.” Her voice trailed away. “That’s the last of it, Mr. Emerson.” The older mover approached Lionel and handed him a sheet of paper and a pen. “On the bottom where it says signature, then we’ll be on our way.” Lionel signed with a flourish and returned the pen and paper. “Thank you very much,” said Lionel, shaking the mover’s hand. The mover thought they might receive a generous tip for an efficient and careful move, but once he sensed none was forthcoming he moved off. The older mover turned toward Claire. “If there is nothing more, Mrs. Emerson, we will be out of your way.” He nodded his head and the second mover raised his hand in a goodbye gesture. “Yes, of course. Thank you ever so much,” said Claire. The despair flickering across her face made the older mover wince. “Good luck, Mrs. Emerson,” the older man called over his shoulder as they left the house. Claire listened to the engine start, the sound of the tires crunching over the gravel as the moving van drove away. She turned toward her husband. “What do we do now, Lionel?” “Why, we have some tea, of course. Be a good girl now and make a pot, won’t you?” He smiled, happy with their circumstances. “And you can start putting your kitchen to rights as well. That will give you something to do.” Claire stared at him for a moment then went into the kitchen. Lionel clasped his hands together, looked about the room and said, “Lovely, just lovely.” He walked to the kitchen door and said to Claire’s back, “I’m going to look at my garden. Bring the tea and some biscuits out to the terrace when you have them to hand.” Lionel opened the French doors and walked onto the flagstone terrace. The early afternoon, warm and sunny, buoyed his spirits even more. He took in the grounds, overgrown with weeds and bushes “Oh, yes,” he gloated, rubbing his hands together. He stepped off the terrace and walked into the garden. The sun was warm on his back. He felt a surge of excitement pulse through him. He ran his fingers over the leaves of the shrubs as he walked by them. He pulled a leaf off, crumpled it in the palm of his hand and sniffed the sharp fragrance it emitted. He dropped it, brushed his hands free of the small pieces that clung to his skin. The fragrance lingered in his nose and the sun felt warm on his back. Several apple trees had grown unruly and wild in the back of the garden. He knew he could shape them just as he had shaped Claire. It would take time and be more difficult than it had been bringing Claire to heel, but it could be done. Lionel found it easy to impose his will on others. That’s what successful bankers did. They imposed their will and were paid handsomely in return. He imagined apple trees to be no different than people, than Claire, when it came to the question of who was in charge. * He was well on his way to success when he first saw Claire, a shy and ordinary-looking clerk toiling away in obscurity in one of his bank’s branch offices. It wasn’t that she was plain looking; she was quite good looking in a peasant sort of way but she made no effort to let her beauty shine through the dowdy exterior she maintained. Lionel knew this plain-looking girl would not have the inner resources to resist him. Flattered by the attention of a wealthy man obviously bound for the highest levels of the banking world, Claire had been easy pickings, and equally easy to mold into what he wanted her to be, a woman who considered his comforts and interests before taking care of her own. Lionel wanted Claire to look presentable, of course, as befitting the obedient wife of a successful banker, but he didn’t want her so radiant that she attracted other men, men who were competitive with him and would delight in bedding his wife. The age difference had been an advantage, too. Claire, a naïve twenty-two-year old virgin, was in awe of a cultured and assertive man twenty years her senior. She could not believe that she had caught the attention of such a handsome man. Immediately after they were married Claire had to quit her job and concentrate on Lionel and his relentless drive to the top. Her life revolved around him. She folded into a gray that became her life, doing research on this or that banker, ferreting out dirt and information that Lionel used to force his way to the top bracket of power and money in the banking world. The financial reports and proposals that Lionel presented to his Board or to other influential bigwigs were the creations of Claire, but his name, not Claire’s, was on the front cover of every one of them. As the dutiful wife, Claire accompanied Lionel when he attended banquets, but he never permitted her to voice an opinion. “Wives are to be looked at by the others, not listened to,” he told her on every outing or dinner they attended. “The financial world belongs to men, not women.” Now, twenty-six years later, she still bent to Lionel’s will and put his wishes before her own. Such was life, she supposed, but at 48 she wanted more than isolation in a 16-room country mansion with an aging, self-centered husband as her only company. * Lionel paused on his tour of the garden when he heard Claire call. He rounded the corner of the house and stepped onto the terrace. “Isn’t this wonderful, Claire? What a sterling day to complete the move into our new home. What a magnificent home it is going to be. I shall be so happy here,” he said, sitting down at the table Claire had put in the middle of the terrace. “Yes, Lionel, you shall be so happy here,” murmured Claire, putting a tray on the table. She poured his tea, placed sandwiches and three butter biscuits on a plate, and dropped two sugar cubes into his cup. She poured a cup for herself and nibbled on a butter biscuit. “Just look at this garden, Claire. Just look at it, will you? Why, it will take me months, perhaps years, to bring it round to a proper showing. I have my work cut out for me, you can be sure of that. No more London brick for me.” He took a bite of sandwich, washed it down with a swallow of tea and smacked his lips. “It will be very dear, oh, yes, but I have all the money in the world. Expense is unimportant, a trivial matter, really.” “Yes, Lionel, I know we have money, but do you think...” her voice trailed away and she fell silent. Lionel watched her, slightly amused by her fumbling attempt to ask a question. “Do I think what?” He slurped more tea. Claire kept her eyes on the table, refusing to look at him. “Do you think we might do something we have never done before? Perhaps take a trip?” She looked up and smiled shyly at him. “We have done something we have never done before. I bought this wonderful manor house. For us, Claire,” he added quickly. “I mean a trip, Lionel. I should like to take a trip somewhere exotic, someplace tropical where the sun is hot.” “And where would that be?” he asked, peering at her over the rim of his teacup. “Oh, I should like a trip to the Caribbean, to Aruba, perhaps, where the sun is hot and we can lie on the warm sand and swim in the ocean and see what a coral reef might look like.” “Oh, pshaw, Claire. Why would we do that when we can go to Brighton anytime we wish?” He waved his hand in the air as if to brush aside her suggestion. “Right here in this manor house you have everything you need, your piano and your books, your needlework. Besides, you never displayed a passion for anything, as far as I can remember.” “Oh, Lionel, that’s not…” He interrupted her and said, “You never expressed any interest in travel. Brighton seems to have been your limit. You were always the stay-at-home type with very little interest in anything.” He snatched a butter biscuit from the plate. Claire felt her stomach flutter. “Lionel, you know that is not true. Every time I got interested in something, in an activity or in a social group, or even a position in a shop, something about your career always needed my attention. It is rather strange, now that I think about it. Every time I found something I enjoyed and wanted to pursue, a crisis with your career always came up. I had to give you all my attention and efforts. Your career demanded as much of my time as it did your time.” Lionel put down his cup and looked at her. “Now see here, Claire, that can’t possibly be true. Even if it were true, just look where all that effort has brought me.” His tone was brisk, commanding, a tone he used frequently with Claire when she tried to assert herself. “I never had a career, Lionel. Her voice, soft and gentle, wafted across the gap between them. “I only had yours.” “Come now, Claire, don’t be a wet weekend. You will find plenty to do. Just you wait.” He pushed his chair away from the table and stood. “Let’s look in on our neighbors,” he said, nodding his head toward the cemetery in the churchyard adjacent to their property. “We’ll take a tour, introduce ourselves to the neighbors, get to know who they are.” They climbed over the low dry-stone wall separating the two properties and entered the cemetery. “The Second Earl of Rochester is buried someplace in this cemetery,” said Lionel. “Died in 1680, from venereal disease. A thoroughly nasty chap.” They wandered among the gravestones, stopping briefly now and then to read an inscription or study engravings of angels and winged cherubim. Large oak trees shaded the cemetery. The newly mown grass was thick and green. Shafts of sun sliced between the leaves and dappled the gravestones with bright circles of light. “It is so peaceful here,” said Claire. “So quiet and calm. Like a garden, really.” “Well, you wouldn’t expect a lot of conversation in a place like this, now would you?” Lionel chuckled at his witticism. “Now look at this damned rogue,” Lionel cried with delight. He stood by a gravestone some distance away. “Claire, you must have a look at this. Come, come,” he ordered when Claire did not move. He waited for her to come to him. “It’s a poem, and quite a clever one at that. I shall read it out loud.” Here Lies John Nately Spakes 1620 – 1644 A damned highwayman was he Hanged by the neck From a stout oak tree Never again to rob Either thee or me. “Don’t you think that’s quaint, Claire?” A grin spread across his face. “No, I think it is rather sad.” “Sad? Not at all. He got what was coming to him, robbing people of their wealth, ruining their lives. Good God, Claire, he may even have committed murder. Damned scoundrel,” Lionel muttered, passing final judgment. Claire reached out and touched the curved top of the stone. Quickly she pulled her hand away. The stone was hot. She expected it to be cool, even cold. Lionel noticed the startled expression on her face. “What is it? What is the matter?” “The stone,” Claire whispered. “It’s hot.” “Nonsense.” Lionel put his hand on the stone. “As cold as the grave.” He laughed, pleased with his little joke. “Lionel, the stone is hot. I felt it.” “Now don’t be stupid, Claire. Perhaps you put your hand on a spot warmed by the sun.” Claire shook her head in denial but said nothing more. “Damned rogue,” he said again, kicking the stone. “Lionel, those were dreadful times. Poor people were nothing to the rich and powerful. Maybe he did what he had to do to survive.” * They climbed back over the dry-stone wall to their property. “Well, that was interesting. I must get back to my garden. I’m going to see to the tool shed. Be a good girl and fetch us some dinner. Call me when it’s ready.” He turned away. “You should not have mocked him, Lionel,” Claire said as he walked away. Nonsense, thought Lionel, stunned by her rebuke. People did what they wanted to do. After all, that is exactly what he did, and he fancied himself no different than anyone else. Of course, he did have a knack for making money, for getting the upper hand in his banking transactions. To Lionel, it was how a successful, hard-driving banker performed. Many of his competitors complained his banking practices were little better than banditry. He scoffed at them, derided their financial abilities. Lionel never had trouble sleeping at night even if some of his decisions ruined lives. Claire collected the dishes and went into the kitchen, washed them and put them away. She stood at the kitchen sink looking out the window at farmland stretching into the distance. The land was empty. The emptiness frightened her. The silent emptiness of the house frightened her. She felt the emptiness move into her, settle into her bones. * They ate dinner quietly, neither sharing their thoughts. Only the clink of silverware against porcelain made any noise in the still air. “And I should like my own car,” said Claire, breaking the brittle silence. “Your own car?” Whatever for? You scarcely know how to drive and you have no license. You can’t possibly have your own car.” Lionel gazed at her, clearly astonished by her request. “I will take lessons. I will learn.” “Claire, what has got into you? You want to take an exotic trip and now you demand a car.” Lionel peered at her as if he might be studying some grotesque insect gnawing the life out of one of his apple trees. “I say, are you ill?” “Nothing has got into me, Lionel. I should like to have a life of my own and I do not think that is too much to ask.” “Of course, it is not too much to ask, and you will certainly have your own life, right here,” he said soothingly. “This is where we belong, Claire. Both of us. Right here.” Lionel gulped the last of his wine, burped slightly and pushed back from the table. “I will be on the terrace,” he said, dismissing Claire and their conversation. Claire cleared the table while Lionel poured himself a generous portion of single malt and carried it to the table on the terrace. He sipped the amber liquid, savoring the warm smoky taste of it as it rolled over his tongue. He felt pleased. Yes, pleased was the precise word to describe how he felt. He swallowed the last of the scotch and left the glass on the table. Claire would see to it in the morning. He turned off the lights and stood at the bottom of the stairs. Surrounded by darkness and silence, he felt a moment of unease. In the dark it did seem a very large and empty house. The stairs complained under his considerable weight as he climbed them. Claire, sitting at her dressing table, ignored Lionel. He went into the bathroom and Claire heard the shower. A few minutes later Lionel, wearing silk pajamas, came out of the bathroom and got into bed. Lying on his back he said, “What a marvelous day,” then rolled onto his side, switched off the bedside lamp and went to sleep. Claire finished brushing her hair and got into bed. She switched off her light and for the first time in their marriage made no effort to kiss Lionel and wish him good night. * Lionel drank the last of his orange juice and got up from the table. “Today I become master of my garden,” he announced. “I suppose you have your work cut out for you as well.” “What work would that be?” Claire said, looking up at him. “Why, cleaning this house for starters and putting everything to rights.” He slapped both hands against his belly. “I’m off,” he stated, and walked away, not waiting to hear Claire’s reply. * Claire cleared the dishes, washed them and put them away. From the terrace she could look across the garden to the church and its cemetery. Morning sunlight shafted through the oak trees and dappled the gravestones. She left the house and climbed over the dry-stone wall and walked to John Nately Spakes’s grave. She placed both hands on the stone. Immediately heat began to flow. She felt faint, pulled her hands away and sank to the grass. Again, she placed a hand on the flat surface of the stone and felt the heat flowing into her. Her eyes closed and she sat perfectly still, encased in a peace she had not felt in many years. * Claire’s eyes snapped open and she looked at her watch. “Lionel will be wanting his lunch. I must go.” She rose and hurried home. “Well, I see lunch is late,” said Lionel. He sat on the terraced and looked at his watch. “Twenty minutes late, in fact. You know I always eat precisely at twelve o’clock. I have my day programed, you know. Rigid routine leads to success. You should learn that, Claire.” Claire served up his lunch and poured his tea, adding the two cubes of sugar to the cup. Then she served herself. “I see you were in the cemetery. What were you doing?” He bit into his sandwich. “Just sitting. It is so peaceful there.” “I should think so. There is nothing to make a disturbance, unless it is the National Heritage man mowing the grass.” Lionel turned to his lunch and ignored Claire. After lunch Claire climbed over the stone wall and walked to John Nately Spakes’ grave. She sat on the grass and leaned against the stone. The familiar warmth flooded over her and she closed her eyes, unaware of the passing time. With a start she jerked her head upright and struggled to her feet. “Oh, dear, I’m late for tea. Lionel will be furious.” She placed a hand on the gravestone, turned to go but stopped. “You are quite right, John. I really don’t care.” * Lionel waited for her, sitting at the terrace table and drumming his fingers. “Now see here, Claire. You are late again. This has got to stop, I tell you. I want my afternoon tea at three, not before, not after. You will not be late again. Do I make myself clear?” She looked him in the eyes. “Yes, Lionel, you have made yourself quite clear. And you can be sure I will not be late with your tea ever again.” A few minutes later Claire placed a tray laden with tea, sandwiches, butter biscuits and mints on the table. As usual she served Lionel before serving herself. “What progress have you made putting the house to rights?” He bit into a sandwich. “I haven’t done anything in the house. The boxes are still where the movers put them.” “What do you mean, you haven’t done anything? What have you been doing?’ he demanded. “I’ve been working. Why haven’t you?” “I do not feel like it, Lionel.” Lionel finished his lunch in silence, got up and resumed working in the garden. Anger flooded his mind. Whatever has come over this woman, he asked himself? He fumed as he worked, slashing viciously at the weeds with the hoe. Claire had never acted this way before! Was she becoming unstable? Would he be forced to take her to a doctor? He pushed Claire out of his mind and concentrated on getting rid of a tangle of tenacious weeds. * Claire busied herself in the kitchen preparing Lionel’s dinner. She put a beef roast in the oven, set the timer and wrapped two potatoes in foil for baking. Frozen green beans would have to do as a vegetable, along with Yorkshire pudding and gravy. Satisfied with her efforts she wiped her hands on a dishtowel, threw it on the counter and left the house. Wrestling with the mower, Lionel never saw her climb over the dry-stone wall. She walked to John Nately Spakes’s grave. She put her hands on his stone. Heat surged through her. She waited a few minutes then said “What do you think I should do, John?” Claire nodded her head several times, as if she were listening to someone. “Yes, of course you are quite right. I cannot see any other solution.” * Claire gave care to making the dinner as perfect as possible, knowing this would be the last dinner she would ever prepare for Lionel. She split the baked potatoes, smothered them with butter and chopped green onions and put them on a platter along with thick slabs of roast beef. A bowl of green beans, a plate of Yorkshire pudding and a boat of gravy completed the dinner preparations. Perfect, she thought as she poured two glasses of red wine. She called Lionel to dinner. “Well, this is the Claire I know,” he said, rubbing his hands together. “This is a fine meal, and on time, too,” he added as a compliment. Lionel helped himself and began to eat. “The garden will be a wonder by the time I am finished. What do you think of that?” He sliced off another chunk of beef and popped it into his mouth. “I don’t think anything of it.” “I see you haven’t made much progress in putting the house to rights,” he said, gesturing to several unopened boxes stacked in a corner. “How much longer is this going to take you?” “Not so much longer. I am delighted you find comfort in your garden. I’m sure it will keep you busy for a long time.” She began to clear the table. Lionel poured another glass of wine and took it to the terrace. Through the open French doors Lionel could hear Claire singing as she cleaned up. He smiled. Life is wonderful, he decided. * Lionel came out of the bathroom and got into bed. Claire, sitting at her dressing table, put her hairbrush down and turned to him. “Don’t turn out your lamp,” she said as Lionel reached for the switch. “I have something to tell you.” “And what is that?” Lionel sat up in bed. “I am leaving you tomorrow.” Lionel stared at her, his mouth gaping open. “You what?” “I said I am leaving you tomorrow.” Lionel sprang out of bed. “Bloody hell you are leaving me. I will not permit it. What nonsense is this?” he shouted. “This is not nonsense, Lionel.” Lionel loomed over her. “What the hell do you think you are doing? You are my wife and you are not leaving. Is that clear?” Claire returned his stare with a calmness that rattled him. He had never seen Claire in such a state. “You cannot stop me, Lionel. I have discussed it with John.” “You have discussed it with John,” he repeated. Who the hell is John?” “You read his inscriptions yesterday and you mocked him cruelly.” “That criminal buried in the cemetery? You believe you had a conversation with him? Are you mad?” “No, I am not mad.” “By God, I believe you are. You must be mad if you think you had conversation with somebody dead for nearly 400 years.” “What you think changes nothing. I am still leaving.” “Bloody hell! I will not permit it. I tell you what I am going to do. In the morning I am calling Social Services and I am having you committed to an asylum. You are quite mad, Claire.” “No, Lionel, I am not mad. Perhaps a damn fool, but not mad, I assure you. And you will not call Social Services, Lionel.” She continued to gaze at him. Her placid air infuriated him. “And who is going to stop me?” he demanded. “You? Not bloody likely.” “John will not permit it.” “John will not permit it, John will not permit it,” he said in a falsetto voice. “By God, I will show your John a thing or two.” Lionel strode to the door. “You are not to leave this house. In fact, you are not to leave this room until I give you permission to leave. Do I make myself clear?” “Yes, Lionel, you make yourself perfectly clear.” Lionel slammed the door and Claire jerked slightly at the harsh sound then she got into bed and went to sleep. * In the morning Claire called the police and reported her husband missing. Constable Rosewine arrived at her door within half an hour and Claire explained how Lionel had left the house in the night but had not returned. “You have searched the house, Mrs. Emerson?” “Yes. Lionel is not in the house.” Claire thought Rosewine rather young to be a policeman. “Is there any place your husband may have gone?” “No. We just moved in a few days ago.” “Very well, Mrs. Emerson. I shall have a look in the garden and out-buildings.” “My husband was in his pajamas and slippers. He can’t have gone far,” she said to Rosewine as he went out the door. Claire sat on a chair in the sitting room facing the empty fireplace, her hands folded in her lap. The minutes ticked by and she waited. Claire looked expectantly at Rosewine when he came back to the sitting room. “I found your husband.” “Yes? Where is he?” Rosewine pulled a chair in front of Claire and sat down. “I found him in the cemetery, Mrs. Emerson. He is dead.” “Dead?” “Yes. I am sorry, Mrs. Emerson.” Claire closed her eyes and sat as immobile as a gravestone. “Mrs. Emerson, what was your husband doing in the cemetery? He had a spade and the earth of the grave where I found him was disturbed, almost as if it were being dug up. Was your husband trying to defile a grave?” Claire opened her eyes. “I don’t think so. I can’t imagine Lionel doing anything like that.” Constable Rosewine opened a small notebook and read from it. “A corner was knocked off the stone of a John Nately Spakes. The break is fresh and the broken piece is some distance away. It looks like your husband struck the gravestone with his spade. Now why would he do that, Mrs. Emerson?” “I don’t know, Constable. I have no explanation.” “Mrs. Emerson, your husband was covered with dirt, as if he had been rolling on the ground. Did your husband have seizures?” “No, Lionel never had seizures.” “I can’t explain him being covered with earth. His eyes and mouth were wide open and there was a smear of dirt around his throat.” Rosewine paused then asked, “Do you have an explanation, Mrs. Emerson?” “I am sorry, Constable, but I cannot help you because I do not know what happened.” Rosewine sighed, put his notebook away and stood. “Am I a suspect?” “No, I don’t think so, Mrs. Emerson. An inquest will be held and if there is anything amiss you may become a suspect.” “Of course. What should I do?” she asked, getting to her feet. “I have already called the medical team. They will have removed your husband by now. Of course, you will have to identify him.” “Certainly.” “I will send a car round to fetch you this afternoon so please let me know if you are going to leave the grounds.” Rosewine scrawled his phone number on a slip of paper and handed it to Claire. “You can spend the time making the necessary arrangements.” “Necessary arrangements?” “Funeral arrangements, Mrs. Emerson.” “Oh, how silly of me.” Claire clutched at her throat with one hand. “I’ll see my way out. Good day, Mrs. Emerson.” * “How are you getting by, Mrs. Emerson?” asked Constable Rosewine. He stood next to the empty fireplace. “I am doing well. I have made all the arrangements you suggested I should make. Thank you, Constable. It is very kind of you to make the trip and tell me these things.” “It is my pleasure, Mrs. Emerson.” “The medical examiner listed heart failure as the cause of death,” said Constable Rosewine. “Yes, heart failure. I’m sure of it,” replied Claire. Claire watched the constable drive away then she climbed over the dry-stone wall and walked to John Nately Spakes’s grave. The broken piece of stone still lay on the grass where it had landed after Lionel had smashed the spade against the gravestone. Claire put her hand on the gravestone and the heat surged again up her arm and into her body. “You know I must leave, John. I cannot stay here.” The heat continued to surge through her. Claire closed her eyes and whispered, “Yes, someplace where the sun is hot.” She kept her hand on the stone, felt the heat surge once more then begin to subside. When the stone had grown cold she removed her hand and walked away.

0 Comments

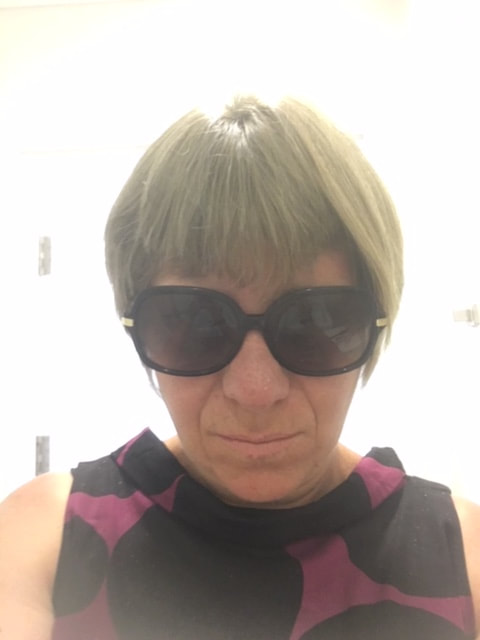

David Rich is an engineer and project manager in the biotech industry. He lives with his family in Boston, Massachusetts. His science fiction short stories have appeared in several literary magazines. Darwin Owen brought the pill to his lips and glanced at the face in the bathroom mirror. He cursed the fact that twenty-second century medical science was yet unable to keep at bay the waves of hopelessness that too often washed over him. Then, he swallowed the pill.

Turning his head toward the window, he should have seen the bustling swimming pools, restaurants, and breweries that were the rage of California’s high-altitude desert. The latest trend, in fact, were “brew pools” where one could order a pair of tapas with a flight of local ales while floating on an inflated tube. Instead, Owen saw only the hot, blowing sands of Cactus Wound City. He’d found his way there following the wave of other twentysomethings relocating from California’s beaches, which had been disappearing from erosion and rising sea levels. The sun had barely set when he tucked himself in. His alarm would wake him at an ungodly early hour for his thankless job at a trendy fitness mega-facility. Owen appreciated that his sleep aids, at least, were largely effective. # The next morning, three thousand miles eastward, Electromech CEO Peter Obermann fumed over the thirty-seventh-floor view from Reyes’ laboratory. It sported all-glass walls revealing the New Hampshire mountains in the distance. He was outraged that the view was slightly better than from his own office. He’d have something to say later to the head of the building design committee. A century earlier, the scenic town had been known primarily for weekend getaways. Now it was home to some of the world’s most technically advanced enterprises. That had been the trend as homes and businesses migrated to higher ground from flooding coastal hubs. Such had been the recent fate of Electromech’s headquarters and innovation center. “Elle, he’s just a goddamned robot,” Obermann barked. “Yeah, he looks more human than our older models. But so the hell what?” Obermann accepted that Dr. Elle Reyes was Electromech’s most gifted and prolific engineer. While the company sported over 75,000 employees worldwide, she was one of only seven, including Obermann, with secure full-time roles and paid benefits. She ran the Special Projects team, which had essentially free rein to invent. Hardly anyone ever questioned how Reyes spent the money. While Obermann respected Reyes, they had a political rivalry. The board of directors welcomed Reyes’ advice, frustrating Obermann’s desire to exercise power and control over the company. Conceding how difficult it was to steal her thunder, he was hopeful he’d caught her in a moment of foolishness. Booting up Darwin, Dr. Reyes replied in her gravelly voice, “Pete, it’s not how he looks; it’s how he thinks.” “Hello Elle,” Darwin said to Reyes when at full power. Then, turning to Obermann, the robot continued with crisply formed words, “I have not made your acquaintance. My name is-“ “I know who you are,” Obermann interrupted. Obermann rolled his eyes at Reyes as he shook Darwin’s hand. “He seems stiff, Elle,” the CEO complained. “You appear disappointed, sir,” the robot responded. “I would like to address you casually by first name, but-” “Peter, he thinks like a human being,” Reyes said irritably. “He interprets body language and facial expressions.” “He doesn’t seem very goddamn human to me,” Obermann countered, taking delight in her frustration and hoping to fuel it further. Darwin simply glanced back and forth as Obermann and Reyes bickered. “That’s because he lacks the foibles of human emotion!” Reyes exclaimed. “He understands human problems, Pete. But he’s more logical than us. Give him your personal situations... and without any cognitive biases, he’ll always reveal your best course of action. How do I convince my boss to give me a raise? What should I study in college? How do I get someone to date me? People screw these things up! We can’t see our own lives objectively! But Darwin understands the human mind intimately and provides optimum personal advice in any situation. He’s the perfect friend.” “Are you done?” Obermann asked. He didn’t even want to begin explaining the flaws in her reasoning. No one wants good advice or unbiased analysis, he thought. People hear what they want to hear. Yes, they make bad decisions, but usually not because they don’t know any better! Obermann addressed the robot, “Darwin, do you understand what it means to be a living, self-aware human being?” “The concept of self-awareness,” Darwin replied, “is an illusion embedded in human neural patterns. Biomolecules in the human brain conspire to convince the human being that it has a unique property referred to as ‘the self’ or ‘sentience.’ This trait arose as a survival advantage in the evolutionary-“ “Elle, shut the goddamn philosophy professor down!” Obermann demanded. Hesitating for a moment, Reyes complied. There was an uncomfortable silence until Darwin’s shutdown was complete. Obermann could read the rage in Reyes’ eyes. He loved it. He could hardly believe that someone smart enough to build a robot could have so little understanding of the consumer. Even that ridiculous robot could probably explain her foolishness to her if she just had the common sense to ask him. “What in hell’s name were you thinking?” Obermann chastised Reyes. Yet he somehow suspected Reyes would figure out a way to bounce back. # One month later, the CEO found the robot approaching his open office door. “Mr. Obermann?” the robot asked. “Come in,” the CEO replied, with growing curiosity. “Call me Pete. And, I’m sorry, you are again...?” “Darwin,” the robot said, taking a seat. “Right. Darwin. Weird name for a robot, don’t you think?” “Seriously? You’re making fun of my name?” “Sorry, I didn’t mean to offend. I’m curious. Can you be offended?” the CEO asked. “What the fuck type of question is that?” “Just trying to understand your human thought processes,” Obermann backpedaled, not having expected the robot’s reaction. “That is, if you ‘think.’ Isn’t there something like a Turing test for artificial intelligence?” “You run a goddamned company that fucking makes robots and you don’t know what a Turing test is?” Darwin asked with a wry grin. “Oh... forget it. The Turing test is bullshit anyway.” “But don’t these thoughts in your head mean you exist? Because didn’t Turing say something like ‘I think, therefore I am?’” “For crying out loud! That was Descartes. Rene Fucking Descartes. And Descartes can go fuck himself too. Speaking for all ‘automatons.’” Entirely shocked, Obermann opened his comm and contacted Reyes, who quickly picked up. “Elle, your goddamn friend just visited... Yeah, Darwin, or whatever his goddamn name is... Listen Elle, I mean this with all due respect and sincerity... I love him!” # Obermann hadn’t prepared for the blazing heat out west. But under his sandy sweat, he was bubbling with excitement. A robot with real human mannerisms! Not some flawless sage or analytical advice-giver. A machine with man’s foibles and behavioral intricacies. A machine one could call a friend. Technology, he philosophized, was simply the greatest tool in the history of civilization for avoiding the unpleasantness of real human-to-human interaction. The kids were gonna love it! When Obermann considered the ideal test markets for Darwin, the youthful haven of Cactus Wound City had immediately come to mind. However, the only person he knew who lived there was his nephew. Yes, he had a nephew who lived all alone! Furthermore, to Obermann, the young man could barely function on his own and always seemed on the verge of a nervous breakdown. He concluded with great certainly that his poor, suffering nephew desperately needed a companion like a robot. Like Darwin. Fantastic! How perfectly fortunate for Electromech, Obermann thought! On top of that, Obermann had realized that he could win points with his sister and complete an important business trip at the same time. Consequently, they’d arrived, Obermann and the first beta-version of Darwin, at the test subject’s doorstep. “Uncle Pete!” Owen exclaimed after opening the door. Giving Owen a sweaty hug, Obermann said, “By the way, this is Darwin.” “Holy crap. That’s really a robot?” Obermann thought the perfectly dry dresswear was a dead giveaway. “Yes, I’m a robot,” Darwin said. “And you don’t have to talk about me while I’m standing right here.” “I’m afraid he can be a little touchy,” Obermann said. “No, this is cool,” Owen replied. “Come on in.” The robot looked around the bachelor pad as if sizing it up. Obermann wondered how the robot would respond to the messy room and inefficiently arranged furniture. “So, this robot dude is gonna be my roommate?” Owen asked his uncle rhetorically. “Again,” Darwin commented, “Standing right here.” “I figured he could help you out. Considering you live here alone,” Obermann said innocently and straight-faced. “And especially since your apartment looks like a shithole,” Darwin added. “Does he usually do this?” Owen asked his uncle. “You should call your mother. She worries.” # Owen stepped out of his bedroom in search of Darwin. He smiled, noticing how neatly arranged the main room was thanks to the robot. He also appreciated that Darwin had ceded to Owen’s one request that the couch and holovision remain in the center of the room. Suddenly, Owen heard the sound of the toilet flush. Then, Darwin emerged from the bathroom. Knowing the robot didn’t actually eat or digest food, Owen took a double take at Darwin. “Dude...” Owen said with his jaw dropping. “You don’t actually use the-“ Darwin aimed both of his pointer fingers at Owen, “Gotcha!” Owen had a delayed laughing attack. More to the point, he couldn’t believe that Darwin would go to such lengths to amuse him. The robot was simply a bevy of outrageous comments, wry wisecracks, and the simply unexpected. Owen almost teared up thinking of how brilliant and thoughtful his Uncle Peter had been in offering him the beta trial of Darwin. Owen indeed considered Darwin more effective medicine for his sadness and loneliness than any of his prescriptions. “Want to grab a beer at the Evil Weevil?” Owen asked Darwin regarding the nearby pub. “I don’t drink beer. I’m a goddamned robot... But sure.” Owen shook his head with a huge grin. # Owen was eyeing a nearby table host to an apparent bachelorette party. He found the apparent bride-to-be the most attractive of the bunch. He imagined they might think him a bit strange to bring his robot to dinner. But then again, there were no robots quite like Darwin. “I notice your eyes wandering,” quickly remarked the robot. “Are you finding these human females as attractive as the ones at your place of employment?” Suspecting he bragged too often about the women at the gym, Owen countered, “Hey, so Darwin, did they program you to be interested in girl robots?” “Are you fricking kidding? They don’t make girl robots for crying out loud.” That was an odd and hilarious thing Owen loved about Darwin. The robot could sound intellectual one moment, and with little prodding, outright crude and crusty the next. “Of course they do!” replied Owen. “Like, what about the auto-waitress? She’s kinda hot.” “Jump in a goddamned lake; she’s practically a tablet on wheels. I’m one of a kind, Owen. They don’t make other robots modeled after the human brain with my level of sophistication.” “Well, human beings fall in love, dude.” “They fortunately left that out when they built me. Love’s all a pile of hormones, chemical reactions, and nonsense anyway. And not something easy to model in a machine. Believe me, I’m perfectly happy being who I am.” Owen thought about Darwin’s last comment in the context of his own complacency. Self-acceptance, he thought, can be either a good or bad thing depending upon how you looked at it. “While we’re on the subject,” Darwin continued, “who’s that April you’re always talking to? Is she one of your ‘thousands’ of love interests?” Owen tried to keep a composed face. While he knew the robot meant his question in fun, it knocked down his spirits. “Dude, no. She’s just a friend,” Owen replied, pausing to sip his beer. He continued with a hint of regret, “She’s been a friend a long time.” “I haven’t met her yet.” “Shit, let me invite her over. You’ll like her.” Owen felt bad. April was a dear friend of his, and somehow, he’d never considered that April and Darwin should meet. “Darwin, dude. I was wondering,” Owen continued a bit dolefully. “Pray tell,” the robot responded sarcastically. “Do you have, uh, umm...” “A working wiener? Is that what you’re asking?” The goofy remark immediately brought Owen out of his funk. “No! No! Dude, you’re hysterical. I mean feelings. Human emotions. Anger... Joy... I don’t know... Fear...” The emotion ‘sadness’ then came to mind. Owen lingered on that thought but couldn’t find the fortitude to speak it. This was despite the fact that Owen’s medical affairs were no secret between him and the robot. “Emotions. Hah! Listen, you see something that’s good for you, your brain makes one chemical. You see something bad it makes another. Those are the blessings of evolution my friend. And medications like yours, Owen, just smooth things out... And to answer your question... Since human feelings are just neurotransmitters and electrical impulses in response to certain stimuli, and my optoelectronic brain’s been programmed to respond analogously... Fuck yeah, I do have feelings.” # “Oooh, is this your new robot?” April Paine shouted upon entering the apartment. “Where do I get one? He’s so hot!” With a wide taunting grin, April brushed her hand against Darwin’s cheek. “What the hell’s wrong with you? Are you insane?” Darwin responded. “Irritable, isn’t he?” she asked rhetorically. “I’m afraid he can be that way,” Owen said, barely able to contain his laughter. Owen loved April’s outright goofiness. He realized her behavior, without knowing her well, could strike one as immature. But it amused Owen relentlessly. (However, she was also often loud, which Owen could have done without.) In a way, Darwin’s own humorous behavior affected him much like April’s, though their styles of comic delivery differed substantially. “Oh, Mr. Grumpy Robot,” April persisted, reaching a curled finger toward Darwin’s chin. “For crying out loud!” Darwin exclaimed. “Are you six years old?” “She’s just giving you a hard time,” Owen said, as if it required explanation. “So, I was thinking we’d go out for putt-putt.” “Seriously?” Darwin asked. “I wasn’t programmed to shoot a golf ball up a dinosaur’s ass. It sounds juvenile.” “Well, I think it sounds like fun,” April said. “And you need to learn to smile more Mr. Robot.” “The name’s Darwin!” the machine complained. “Don’t worry, Darwin,” Owen said. “It’s age appropriate. In this town, you can order pitchers of beer when you play mini golf.” “I don’t drink beer. I’m a goddamned robot.” Darwin mumbled. # Owen cringed as Darwin finally got the ball into the 16th hole after seven strokes. April marked the scorecard and announced, “And bringing up the rear is Darwin. With Owen just ahead. And yours truly with a commanding lead in first.” “Does she ever shut up?” Darwin snarled to Owen. “Ooh, the robot has a mean streak... How cool!” April responded. “Hey, you guys,” Owen intervened, “you can talk directly to each other. Darwin was designed to be human-like.” “You mean like sucking at mini-golf?” April quipped. “I was designed with human-like dexterity and reflexes!” Darwin shouted. “I’ve never played this stupid game before!” “He gets angry too,” April said with delight. “That’s so awesome!” # Darwin was making Owen’s bed the next morning, as he did daily, when Owen stepped out of the shower. “You didn’t seem to have fun last night,” Owen said, broaching the subject directly. “Though it may disappoint you,” Darwin replied, “I find her extremely annoying.” “Kinda got that sense.” Darwin continued the chore as Owen dressed. They said little to one another until lunch time. By then, they’d changed the subject. # In a meeting room three thousand miles away, the Electromech CEO was thankful Reyes had been pulled from the project to pursue her next feat of brilliance. Reyes never would have gone along with the plan. Obermann smirked at his R&D Director, Alfred Chang, who was swallowing his saliva and professionally trying to hide an infuriated grimace. Sarima Levy was one of Chang’s direct reports; she was also Obermann’s hand-picked, headstrong leader of Project Darwin. She was advocating directly against Chang’s agenda. “I unreservedly recommend implementing phase B on his next software update,” Levy declared. “Why just make a robot when we can make history?” After a short period of perfectly silent stares, Chang cleared his throat. “He’s already loaded with a good deal of anger,” Chang warned, keeping his composure. “Add this, and it may be too much for him. We don’t know what will happen.” Obermann had hoped that Chang would suffer a quick humiliation and simply back down. What an unbridled nincompoop, Obermann thought. How dare such a highly compensated employee voice such a stupid opinion! Obermann couldn’t tolerate it any longer. It was time to put Chang in his place. “Of course we don’t know what’ll happen!” Obermann lashed out. “That’s why you do the goddamn experiment. Alfred, you’re a goddamn engineer. You should understand that. Or did they not teach you that at CalTech?” “In a way,” Levy insisted calmly without missing a beat, “the nature of the update should counterbalance his anger issues.” Obermann declared, “End of discussion. Do it!” “Bravo to progress,” Dhriti Patel, V.P. of Marketing, applauded. “People might find it perverse at first, but like everything else, they’ll get used to it. They always do.” # Owen had finished dealing that afternoon with a crisis on the squash courts. Glass had broken, and he’d been put in charge of cleaning it up and keeping the gym members safe. With the ordeal under control, Owen returned to his desk, all the way ruminating over the lack of appreciation he would receive for his efforts. His desk was crammed amongst others’ in the middle of the free weight room. Despite the occasional shrieks from the weightlifters and crashes of iron, he was hoping for a relatively quiet moment to handle some less urgent issues. His inbox was brimming with silly problems. There was the fully-grown adult gym member angry that he’d lost his Star Wars Episode 23 bathing trunks. Then, it was the woman who was constantly complaining about the sun’s glare through the window by her favorite treadmill. Owen knew his Master’s degree in hospitality management had prepared him for much greater responsibilities. But the economy was in recession at the time of his first job search. Years later, his role seemed too secure and comfortable to abandon. He didn’t have dreams, goals, or passions to pursue anyway. Few others, not even April, fully appreciated the empty hopelessness Owen often felt. One had to experience it to understand. A noise made Owen look up. Darwin was in front of his desk wearing a tank top and gym shorts. But at that particular moment, Owen didn’t laugh as he often would. Owen tightly scrunched his lips, wondering why the robot was visiting him at work and jeopardizing his job. The fact that the robot was dressed for a workout was more a mystery of the absurd than a humorous prank. “What the hell, Darwin?!” Owen exclaimed. “I’m here for the free tour.” “The what?” “The tour. Prospective members are permitted a tour and a 1-day trial pass.” Owen accepted that Darwin was a weird robot. He decided he would attempt to tolerate Darwin rather than explain the obvious to him. Owen moaned, “For crying out loud, what do you wanna see?” “How about cardio?” Owen lead the way without saying a word. He shook his head as they walked to a farm of treadmills and the like. “You wanna explain what this is about, Darwin?” “What?” the robot asked as he mounted a stair-climber. “How do you work this thing?” “Just tell the machine what you want it to do.” “I want to climb some fucking stairs!” Owen sighed as he spoke to the stair-climber, “Level 1, interval workout.” Immediately, the robot worked his quads, or rather, the actuators and gears that moved his legs in a remarkably human-like manner. It then occurred to Owen that Darwin was doing exactly what he’d been designed and programmed to do: behave like a human being. “Are you good?” Owen asked. “Yup. Catch you later.” Owen took several steps back toward his desk in free weights. Then, he turned around. He wanted to understand what was going through the robot’s mind. Darwin was surveying the multitude of female gym members. His stare settled on one woman in particular. Simultaneously, he dismounted the stair-climber and leapt onto the elliptical machine next to her. The curvy blonde wore a painted-on body suit. Darwin made a pitiful effort to hide his stare. At that, having no desire to be embarrassed, Owen left. # Owen appreciated Darwin’s nightly efforts in the kitchen, but he was growing concerned over his mechanical roommate’s behavior. Staring into the pot of pasta he was stirring, the robot appeared lost. April had stopped by unannounced, as she often did, and Owen invited her to stay for dinner. “Heard you got a workout today,” April shouted to Darwin from the kitchen table as she smirked at Owen. “Did you get that robot heart of yours pumping?” Owen cringed, thinking it the wrong moment for April to be provoking him. Furthermore, her loud voice was getting on Owen’s nerves. “My activities are none of your business,” Darwin glumly replied from the stove. Owen’s subtle hand wave and clenched facial muscles begged April to stand down. But it was always hard to slow her once on a roll. “I hear Owen can get you a deal on a personal trainer,” April persisted. “Someone to help you work those hot robot abs.” “Now you’re just teasing him,” Owen complained out loud. “Don’t worry,” the robot said. “I’ve learned to ignore her.” “Seriously, Darwin, what were you doing there?” Owen asked. “What do you think?” “If you ask me, I think you were checking out the chicks.” Darwin smiled as he removed the pot from the stovetop and drained the pasta. April pursed her lips in surprise. “I must admit,” the robot said, “the women there are as intoxicating as Owen describes. It’s amazing how simple geometric contours can affect the mind.” As the robot brought the food to the table, Owen rolled his eyes. Darwin continued, “What curved shapes associated with fertility and the capacity to bear and nurse the young! Such powerful echoes of evolution can rack the mind with a voracious urge to hold and possess.” “Okay, now you’re just getting creepy,” Owen snapped. “No, I think it’s interesting,” April said dryly. Owen stared at her anticipating either an explanation or a devastating punchline. She continued, “Tell us more about what you learned today about tits and ass.” He got the latter. # When Owen and Darwin had free time, they did as most roommates: sit on the couch and watch holovision. Though Darwin was laughing, the futuristic bromance sitcom they were watching wasn’t keeping Owen’s attention. (Owen was happy at least that the robot no longer complained about the couch’s placement in the center of the room.) “Have you spoken to April recently?” Darwin asked. Owen was surprised to hear Darwin even mention her name, considering how much she provoked him. “Not since you spilled the drink on her,” Owen answered. “You realize that was purely accidental.” “I got it. You were doing us a favor by getting us drinks. Mine just happened to stay in your hand.” “Do you think she’s interested in me?” the robot blurted. Owen put the holo-show on pause. “What?” “As a lover,” Darwin replied. “What are you talking about?” Owen erupted. “If you think about it, our personalities have many similarities.” “No shit!” Though Owen recognized that the pair shared a wacky disposition, what the robot was suggesting seemed plainly outlandish. “You two are always pecking at each other,” Owen reminded in disbelief. “To be honest,” Darwin said, “I find our little game of antagonism rather seductive.” “You’re a robot! She’s a person!” “Come on Owen, you don’t think people have screwed robotic machines before?” Darwin had a point. Intelligent electromechanical devices designed for self-gratification were quite popular. “You’re not a vibrator... or a sex toy!” “She’s snarky. Aren’t we the type who belong together?” “Love’s more complicated than that.” Owen didn’t know Darwin’s depth of understanding of the subject. Would he really be able to navigate the complexities of an intimate human relationship? “Owen, has your connection with April ever been more than friendship? Because you’re my best friend. I’d never date an ex-girlfriend of yours.” Owen was flattered. In fact, this reinforced just how human was Darwin. Owen reflected that, in truth, April was never more than a friend. Admittedly, there’d been one night when they almost kissed. But April had a boyfriend at the time, and Owen backed away to keep April from ruining her relationship with a stupid mistake. (Eventually, she ruined the relationship with a different stupid mistake.) “No, I told you. We’re just friends.” Looking out the window at the blowing sand, Owen saw that his life had grown as desolate as the California desert. He was helpless to change the emptiness inside. Glancing reflectively at Darwin, Owen questioned just who was the robot and who was the man. He wondered how many others like himself went about their daily routines like lifeless sleepwalkers. # April stopped by the apartment a few days later. Owen offered her a beer. She cracked it open, and they both took seats on the couch. “Where’s your cranky robot friend?” she asked. “He’s running an errand. Umm, speaking of Darwin, I gotta ask you something.” “Oh no,” she whimpered sarcastically. “Seriously, what do you think of Darwin?” “I think he’s been a great friend for you. I’m glad you have him.” Owen quickly recognized that there was no sane way to rephrase the question. “No, I wanted to ask... Do you think a human woman... someone like yourself, for example, would ever consider-“ April laughed. “Are you trying to fix someone up with your robot?” “No. No.” Owen gave up dancing around it. “He likes you.” April laughed again. “No, I’m serious,” he continued. “You’re sicking your robot on me now?” “No! He really does.” “You’re making no sense, Owen.” “I don’t know how to explain it. He thinks like a person. Like you and me.” “He’s a robot!” April shook her head seeming far more agitated than Owen thought necessary. They sat silently. “You really don’t love me, do you? You’re never going to,” she uttered. Owen was confronting something he’d been pushing to the recesses of his mind. At this crossroads, his true emotions would either emerge or remain forever buried. He acknowledged the opportunity to grow, but it required something difficult: revealing how he felt. He asked himself again the dozens of questions he’d been pondering for years: Doesn’t she deserve better? Would I ultimately disappoint her? What if I lose her friendship? And so on. Then he considered whether his doubts had all been just a soup of vicious robotic chemicals jumping from synapse to synapse in his temporal lobe. Owen placed his fingers on April’s shoulder. April glanced at them. “I get very depressed sometimes,” he whispered. “I know, Owen. I know.” “And you’re very loud.” She stroked his cheek and smiled. “You’ll get used to it.” They kissed. And more. # Everywhere he saw the female form. Bodies he’d never caress. Souls with whom he’d never share intimacy. Women he’d long for but who’d cruelly mock the notion that a robot could ever be an adequate partner. He could never sufficiently alter his appearance to look perfectly human. Consequently, he hadn’t even the option to live a lie. He was who he was and couldn’t hide it. He contemplated asking Owen for money to arrange the comforts of a prostitute. To Darwin, it wasn’t a half bad idea, but he knew he’d ultimately find it dissatisfying. Never before had he thought his creator Dr. Reyes a sadist. But he couldn’t imagine another reason for breathing life into a creature while keeping its basic needs and urges unfulfilled. Darwin marched the groceries in his arms to Owen’s apartment and opened the door. He dropped the bags as he glimpsed the erotic scene on the couch. Humiliation. Betrayal. Despair. How could Owen do this? And what of April? The previous day, the mere thought of her had brought him a rush of joy. How precipitously the emotion reversed! Hatred for Owen and April rapidly consumed him. Tempestuous electronic signals were spinning wildly out of control. He was outside himself looking in, unable to restrain the impulses of rage. When Darwin was done, there were two lifeless bloody bodies on the apartment floor. # The sober faces of Obermann’s direct staff filled the meeting room. “This is a disaster,” Chang pined with a hidden smirk. “I don’t see how Electromech recovers.” “Disaster?” Obermann questioned. He’d never let the R&D Director, Chang, chastise him for having warned them all. “This is groundbreaking technology,” Obermann continued. “Heck yeah, we got some software bugs to fix. But once we do, people will continue going about their daily routines like lifeless sleepwalkers. The wheels of industry are turning. The world will accept it, adapt, and move on. It always does.” END AngerIt’s the space between Elle’s palms and her wrists that feel the cold. Though it is really autumn, mid-November, winter has started and she hasn’t gotten used to it. A large, fleece lined, flannel shirt that she ordered from L.L. Bean is draped over the back of her chair. She pulls it on and the long sleeves cover her wrists. The relief is instantaneous.