The Scallops of Rye Bay4.30 on the rough, that’s what she said…where is she, she should be here by now…

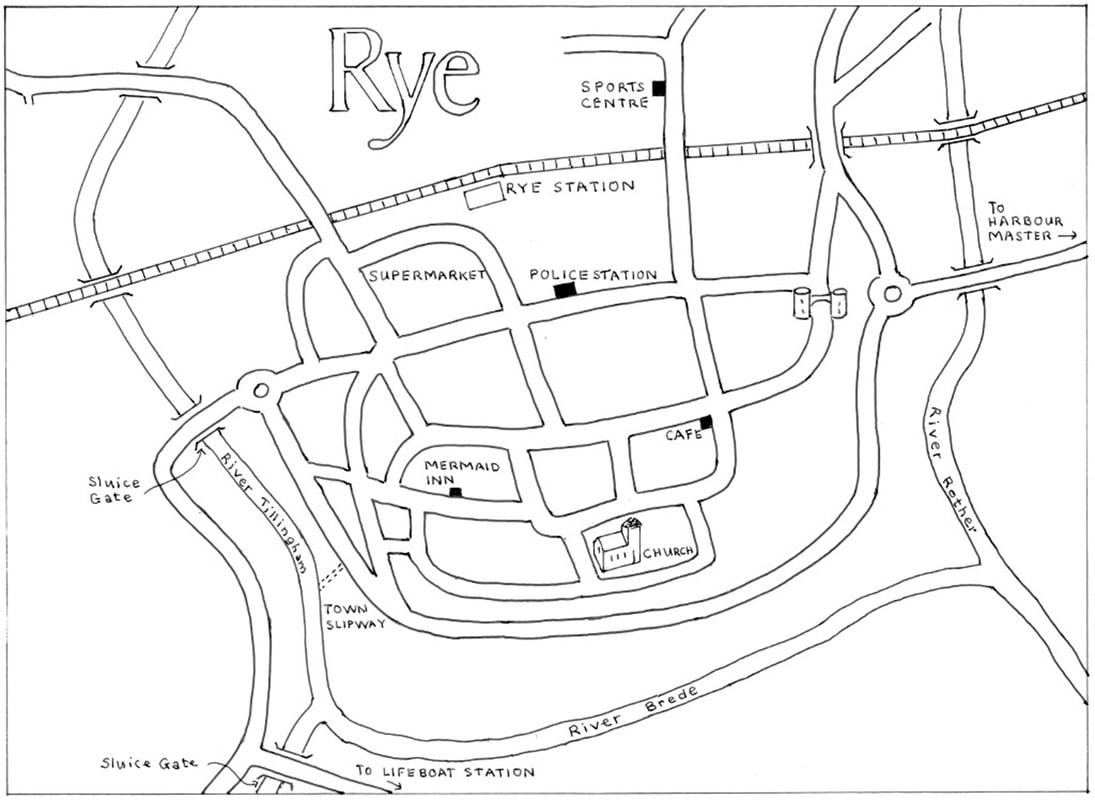

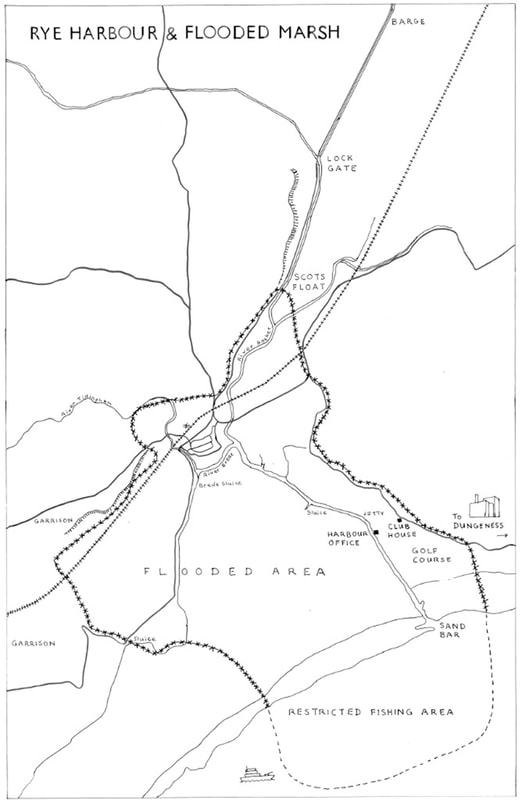

It’s all a rough now, she could be anywhere on these overgrown greens. But all he sees are dark shadows of the night and the faint menacing glow of the burnt-out power station jutting out to sea in the distance. Turning around, he takes the full brunt of driving rain and westerly wind. On Fairlight hill, the blurry sight of the red light on the coastguard mast seems to flicker. Directly below him, under the dunes, the harbour lights flash green and red along the river’s edge. Upstream, the town is in blackness, the power cut for days now. Where is she? He understands her need for secrecy, they all have secrets, but it’s always him that has to wait, get soaked or frozen to the bone, while waiting for her to slip out under cover of the night. He stares at the old clubhouse: that’s where she lives. Is she there? She’d moved in, commandeered the place once it was obvious that no one would ever play golf again. He knows he can’t knock, and sometimes when the weather or the waiting gets too much, his resolve weakens, forcing him to leave. Hanging on, pacing the greens, he sees a lantern swing in an unseen hand as it leaves the clubhouse. A minute later, he hears the sound of an old diesel turning, spluttering, before starting up. Tyres crunching on the gravel road, the truck slowly drives away; it no longer has any headlights. With her husband gone, she’s straight out onto the greens. ‘Inspector French…’ Shouting over the blustery wind, knowing no one else in their right mind will be around, she wanders across the greens towards the sea. Hearing but not seeing her, he heads towards the house. They pass each other, she ending at the dunes, he near the house. Damn, this always happens and he reluctantly gives a flash of his torch. Feeling like a fugitive, he smiles; after all, they are all fugitives. ‘There you are,’ she exclaims, slightly out of breath. Staring, trying to make out each other’s features in the dark: her messy black hair blowing with the wind, and he with an unkempt beard. Both are thin, as any others left alive in the Zone. It’s better in the dark, he thinks: hiding, not seeing, not showing. ‘He’ll be back at sunrise, preparing the boat for tonight, that’s not much time.’ There’s never enough time for this; besides, her husband’s always preparing the boat and always back by sunrise, everybody is. Grabbing his hand, she hurries them to the clubhouse. It’s even darker in the house. It reeks of fish. Wasting no time, he pushes her back into a tattered armchair, one he knows well, one they had always used when things were good. That was a year or more ago. He can’t remember exactly, before the lockdown and before the power station blew. Now they are cursed, creatures of the night. It’s better in the dark. Half-undressed, he sits at the kitchen table. It’s cold. No one has heating anymore and the only hot water for bathing comes from a once a week shower session at the old swimming pool. That’s if the power works; it’s less frequent these days. He starts to dress, his warm body quickly cooling. He can make out her pale body, legs hunched up, still in the chair. ‘Aren’t you cold?’ ‘After that!’ Her features start to become visible and he looks out the window to the east. A light sliver on the horizon, cutting the night sky, tells him to move. ‘The light, he’ll be back soon and I don’t want to get sick,’ he blurts out. ‘Or have a fight…do you have anything?’ From his sodden coat pocket, he takes a small metal box. ‘Here, help you sleep.’ ‘And forget…’ The growl of the diesel sends him to the back door and out onto the greens. She had said that she had something for him: important information. It would have to wait. She shouts after him: ‘Later, at the church…’ He’d thoughtlessly lost track of time in the clubhouse and now, as the dark beneath his feet starts turning green, he begins to run. Two minutes later, as he opens the harbour office door, the sun sparkles off the river. He slams the door shut. The blinds are down, moving gently with the wind as it pushes through broken window seals. Soft light flickers through the room, but it’s safe enough. In the semi-darkness he changes, hanging up his soaking clothes to dry. This two storey box is home: high enough to be out of reach from flooding tides and out the way enough to be secure. Not that security is an issue anymore…but there was time. He glances at the desk under the lookout windows. Covered in dust, his police gun lies there. He hasn’t picked it up in half a year. It feels a life away, but he can never shake what had really happened. * * * A virus happened, tearing through the country, battering communities. There had been a lockdown, each area keeping to itself. Containment seemed to work. Out of a population of nine thousand, Rye had about a hundred deaths. At the time it seemed a lot, but nothing compared to what came next. As head of the local police, his job became easy: crime almost disappeared. But then, due to lack of manpower or just incompetence, the aging nuclear power station at Dungeness had a small explosion. It flared bright for a day and night before suddenly reducing to an iridescent glow that has never gone away. As the wind blew in from the west, it was said that little radiation fell on Rye. This false sense of safety was soon cut short. Four days later, people started dropping like flies. Radiation and the virus didn’t mix together well, unless it’s to wipe out an entire population. Rye became toxic. It had been chaos. Paranoid of some super-virus developing, the military cordoned off the area with barbed wire. Armed patrols, in full radiation protection gear, shot anyone leaving, and there were many. Shops were looted and some smartarse sabotaged the sluice gates along the rivers Rother, Brede and Tillingham, jamming them open, thinking that if the marshes were flooded, any radiation would soon be washed out to sea and things return to lockdown normal. After some heavy rainfall, the first big high tide pushed through the sluice gates, flooding the entire marsh and lower town; even the railroad was underwater, the level rising to within an inch of the platform edge. In fact, only the small town on the hill, cut off as a small island, and a few high points like the clubhouse and the harbour office stayed dry. It had made matters worse not better. Infuriated authorities even ordered dogs and sheep wandering out of the Zone to be shot. Day and night, he’d heard gunfire. Inspector French remembers his staff, all good people: dead by the end of the second week. The authorities had quickly put him in charge. Now that the power station was down and irreparable, they promised to reroute the supply and deliver food. Insisting on a head count first, he’d lied, telling them two thousand, maybe more. He didn’t know the number, maybe five hundred, maybe less. Rye was desperate, some people having been murdered for a can of beans looted from the flooded supermarket by the station. As an official figure, he had been blamed and accused: somehow this was his fault. After a gang of locals threatened him, he feared a witch hunt and barricaded himself in the police station. Pulling the blinds, he hunkered down with a gun and few supplies. The promised food drop never materialised and his radio soon went flat. When his food was finished, hunger and panic forced him to venture out. The town was deserted. The receding tides had left bodies everywhere. The place stank and rats were rife. Daylight had an odd other-worldly hue, a yellow glow that made him sick and dizzy, sending him back to the station. That night, he tried again. He needed to charge the radio – but how? Visibly holding the gun to show moving shadows in the night he was armed, he tried starting the police cars in the yard. They had all been flooded out, batteries dead. He cautiously wandered into town, uphill where the water hadn’t reached. Trying every car door, he found one open, keys in ignition. There were no bodies here, they must have been moved, and the road was clear. Someone had taken charge and that scared him. One man, if he were still alive, knew everyone and everything, but it was risky. Desperation drove him on, across the bridge where some minutes later he stopped outside the clubhouse. Just do it, he thought, and was soon banging on the door. Hillary’s husband answered. Inspector French saw her silhouette standing in the room. Although dark, he sensed her blushing. ‘French, what do you want? I hear you’ve been hiding from the lynch mob.’ He stood looking at the man whose name he had now forgotten but still frightened the living daylights out of him. He had a reputation. Hillary’s husband looked down at the dark shape of the gun clasped tight in French’s hand. ‘Like that, is it…?’ ‘No, no…It’s not safe, can I come in?’ He felt pathetic. Hillary stepped forward. ‘Of course, are you hungry?’ He nodded. ‘Scallops and seaweed, help yourself.’ ‘You eat sea-food, isn’t it full of radiation…they let you fish?’ ‘Not glowing in the dark yet, besides, those other things didn’t kill us…been eating them for weeks, up to you. Coastguard dropped flashing buoys three miles out, signage reading: “Boats passing beyond this point will be destroyed.” It’s not a big area, but big enough for the three boats still working… saw a boat blown clean out the water, pushing its luck. Fool.’ Hillary’s husband struck a match, the flare momentarily lighting up the room. He lit a candle on the table. French avoided looking at Hillary and focused on her husband. In the flickering light, as shadows danced across his scary face, French noticed that he had a glow: not of radiation but of health. ‘You don’t look so good French, you succumbing?’ Without thinking, he picked up a plate of food and started eating. Hillary’s husband gestured to the armchair. It felt so wrong, but to avoid suspicion he sat down anyway, glancing at Hillary who quickly turned away. The seat was warm and he immediately stood back up. ‘I need power for the radio,’ he urgently blurted out through a mouthful of food. ‘Can you get us food, electric?’ ‘Do my best.’ ‘The harbour lights use wind and solar, got that working. Why not stay at the harbour office, it’s empty. Be safe there, you can a get small amount of power from the console and water from a well we sunk out back.’ ‘Who’s been cleaning up the town?’ ‘People, got their patches, not safe for the likes of you, not now, and before you ask, we all feel funny in the daylight…we’re relying on you.’ * * * And that’s how he’d arrived at the harbour office, soon learning that he was a very ex-police inspector, his very existence depending on securing food and power and the grace of Hillary’s husband. With the radio charged, that’s exactly what he did. Food was regular but the power intermittent. By greatly exaggerating population numbers, he’d managed to horde a huge amount of food, storing it in the church at the very top of town. Now, with numbers dwindling, there only being around a hundred people left, no one is interested in Inspector French anymore; well, only one but that’s still a secret. Today is a food drop day, or rather tomorrow morning dead of night. The authorities sensibly insisting the drops take place in total darkness. They too had learned to stay far away from the local light. He wakes before the alarm; it’s not yet dusk. He opens a tin of mixed beans and tears off a piece of smoked fish. With all the driftwood floating in from sea, the fishermen had made a smokery behind the jetty, a stone’s throw from the harbour office. Dipping the fish into the can of beans, he licks it clean and takes a bite while watching the orange glow of the winter sunset fade around the edges of the window blinds. They are grey by the time he’s finished and near black when he grabs his coat to leave. At first, being out all night seemed wrong, against nature itself. But now he craves it, even gladly suffering the howling winds of winter. The long summer days had been intolerable. He had spent most of them at the abandoned leisure centre, mindlessly exercising behind blacked-out windows in the gym, or, before it broke, cooking in the sauna. He’d never known such boredom, and nothing brought relief. Now, in the dead of winter, he rarely wastes a precious moment of the night indoors…unless he’s spending it with Hillary. The waxing moon illuminates the jetty. The hum and rattle of the boats below tells him that they’re ready for work, just waiting for the tide to rise. They always go together, staying close, as their radios and phones no longer work and the life boat’s long been without a crew. Here, a year ago, the moon showed bodies floating out to sea. Leaving the river and flashing harbour lights, he mounts a bike and slowly cycles through the inky night. On the road, behind the high barbed wire fence to his right, is the distant glow of the power station. Dismounting, he leaves the bike under the old stone archway. Walking up the potholed road towards the church, he turns left, passing his favourite coffee shop. It’s now a ruin: its bay side-windows completely demolished where he had once misjudged the corner, driving the tractor clean inside. Outside the old town hall, the dark shape of the huge tractor with its high-sided farm trailer stands where he had left it. An engineer, who got stuck in town, keeps it going. It even has some working lights. Skirting around the tractor, he enters the passage to the church. He stops. In the dim moonlight, he checks his watch. In front of him, the church door is ajar. Candlelight flickers from inside. In the soft wind, he hears an owl and then the loud clang of the church clock bell. Looking up towards the clock, it’s far too dark to read the time. But he knows it’s seven. The vicar still winds this ancient time piece, fastidiously taking care of it. Rye time is Church time. They all rely on it, and he adjusts his watch. Inside the church, the wind makes shadows dance. He pulls the door. It closes with a thud. The wind stops and the candles settle down. The vicar sits facing the door. He’s always there and Inspector French is never late. The vicar, once serene, is now a troubled man, no longer having any words for comfort. He’d once told French that he wished he’d perished when the power station blew. French had offered him a biscuit then, as he didn’t know what else to do. In the stillness, looking across the shadowed church into the vicar’s deep black eyes, he asks: ‘Does all bode well?’ The vicar deliberately waits before replying: ‘As well as can be expected…Inspector French.’ This is their weekly ritual, one that’s never varied, near a year. Next to the vicar is a small table. On it sits two cups of steaming tea. When the power’s down, the vicar collects wood from the high tide mark to boil a kettle somewhere out the back. French sits down and drinks his tea. The vicar studies him before asking: ‘Will you have help tonight?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘I too would like some local help but the flock seems rather thin these days.’ French smirks. ‘Mrs. Johnson’s all alone. Sure she’d gladly help you out.’ ‘You think?’ ‘Yes vicar, I think you should invite her for a very long cup of tea. I’ll suggest it when I see her next.’ ‘I’d be grateful.’ What you mean vicar is that you’ll keep your mouth shut about me and Hillary, French momentarily fumes. He gets up. All the pews have been removed and the church is crammed full of boxes and crates. Even with the vicar’s thoughtful care, there’s hardly any space. Picking up a burning candle, he walks to the tower door. Inside, he takes a pair of binoculars hanging on a nail in the wall, placing them around his neck. He ascends the tiny twisting stairway to the clock room. The vicar has made a bed up here; the whirring of the clock and harsh clanging of the clock bell must give solace, but he doubts Mrs. Johnson will feel the same. Climbing a vertical wooden ladder, he enters the bell house. Covered in bat dung, the bells haven’t rung in ages. No one goes to sermons anymore, gets married or, oddly, has children; even the dead don’t come as they are tossed over the bridge into a fast receding tide. They only come for food. Carefully placing the candle on the floor, he walks past the bells, climbs the steep wooden steps and pushes open the small parapet door. Once a week, up here outside the bell house, he surveys the terrain. At first, the authorities had wanted to know what was going on in Rye. He had told the truth: affliction, flooding and despair, or the odd body, obviously murdered, lying in a street. Nothing could be done and they soon stopped asking. But he hasn’t stopped these weekly checks; it gives meaning to his life, pretending to be a policeman once again. The wind is soft and cold. He pulls his woollen hat down over his chilly ears. The walkway goes all around the parapet. He starts with the harbour, its lights flashing all along the river. Out at sea, the three boats trawl along the nearby shore; they too have lights. He turns, focusing the binoculars on the power station: the hot glow never changing. Walking along the east wall, he stops to survey the hill at Wittersham. The garrison there organise food drops using a long barge moored on the military canal. Usually he can see the barge lights and a glimmer of the garrison stationed on the hill. Tonight there’s nothing, it’s all pitch black, except for moonlight, shimmering on the flooded marsh. Perplexed, French quickly moves to the other side of the bell tower to survey the hills at Udimore and Winchelsea. There should be lights of other garrisons up there, but there aren’t. Worried, he hurries back down to the church. He feels panic coming and finds himself staring blankly at the vicar. ‘Seen a ghost, old boy, must be a ton of them round here. I’ll put the kettle on, have a biscuit.’ The vicar disappears. Unable to think, French paces the church. Calming down, he rifles through a box and grabs a pack of biscuits. When the vicar returns, French is sitting by the table. He‘s eaten half the packet. ‘Chocolate cookies, only the best for the Inspector.’ ‘It’s not like we’re short.’ He wants to tell the vicar about the lights, but it might be nothing, just a power outage. But that wouldn’t explain the barge though; its lights, powered by the engine, are always on during his weekly parapet watch. They don’t talk. French checks his watch; there’re some hours before the food collection. Finishing his tea, he stands up. He needs to move; besides, he’s just heard the tractor start. He looks at the vicar sitting on the chair in his large overcoat, woollen hat pulled down tight over his head. For a moment, they stare at each other and then the vicar points. French follows the direction of the finger. It points to a cross, just visible in the flickering shadows. ‘It shouldn’t be a cross you know, but a scallop.’ French waits for more. Nothing comes. As he leaves the church, the vicar calls out: ‘I’d be terribly grateful.’ Outside the church, the engineer is inspecting the tractor with his flashlight. Batteries are scarce and carefully rationed. ‘Be good for tonight, don’t worry.’ The engineer smiles and French nods, feigning his own smile. He’s never worried, it’s always good. The whole town worships this tractor and he’s its priest. He walks around to the back of church, startling a few sheep sitting on the grass. Sheep are everywhere, even on the golf course where they keep the grass and weeds quite short. No one eats the sheep, they are full of radiation. He laughs aloud at that thought. It seems that daylight doesn’t trouble them. Everyone now lives in the town, except for him, the fishermen and Hillary of course. It‘s safe from floods and, although most people are solitary, there’s a sense of belonging; the last hundred holding out for some pipe-dream rescue day. Many of the houses have been ransacked, doors hanging off their hinges, windows smashed. The few untouched are lived in. French wanders through the streets, stopping outside the Mermaid Inn. It wasn’t looted as the owner had fired his shotgun at anyone coming close. He’s gone now and its sole occupant is sitting on the entrance steps. She strokes a black cat, its eyes shining in the moonlight. He can’t quite believe how good she looks. ‘Mrs. Johnson, the vicar’s invited you for tea.’ She looks shocked. ‘Tea? He’s half way round the bend that one.’ ‘Just saying…could do with,’ he pauses, thinks a moment but doesn’t continue. She and the cat both stare at him. Feeling awkward, he leaves. There, he’s done what he’d been asked. Halfway round the bend, yes, that quite the perfect tag. He stops at Strand Quay. It’s full of wrecked boats, some still tethered to their moorings. He thinks about his mother and her fine house in Spain. Is she still alive or had the virus got her and the house a total wreck? Not wanting to think about such things, he keeps walking around the town. A few people greet him but he doesn’t stop. By the time he’s back at the tractor, his anxiety has waned. The engineer’s gone and Hillary is waiting. ‘Got some biscuits and the vicar made a flask of tea.’ ‘Did he say anything strange?’ ‘Only the best for The Inspector, is that so strange?’ Hillary is smiling but French knows if they don’t take care, trouble’s coming. He checks the time; the clock bell will soon clang 12. It’s time to go. Once out of town, along the Military road, she snuggles close to him. The bright headlights illuminate the flooded road. She turns the radio on. It hisses loudly, joining the din of engine hum and wheels splashing water. ‘Not that song again,’ French laughs. Laughing too, she turns it off. Radios had long stopped receiving signals. The authorities had seen to that. Maybe good news from the outside world would result in Rye hysteria and mass breakout. He doesn’t know, but he does know that they are lepers, living in their radioactive colony with no chance of escape. On the road ahead are concrete blocks. Behind the blocks, the perimeter fence glints in the tractor’s lights. This is as far as anyone can go. He turns right, slowly crossing the river bridge over Scots Float sluice gate. The sluice is jammed open, damaged by the sabotage. He reverses the tractor, the trailer level with the slipway, a steep ramp that was used for launching boats. They leave the tractor and stand on the bridge, arm in arm, looking up the river, waiting for the barge. It’s due soon and it’s never late. The first time he’d picked up food, he’d tried talking to the soldiers on the barge. Although suited up in radiation suits and respirators, he knew they could hear him and he’d hoped they would shout back. But the soldier at the front had warned him off, raising his rifle, squarely aiming at his chest. He never tried again. All alone, that first time had been hell. The barge has a crane to unload the crates and boxes on the slipway, or, if the slipway is under water, the river bank. Loading the trailer by hand, he’d had to labour hard. Not managing to get back in time, the morning light flooded the tractor cab at the entrance to the town. A dreadful feeling overcame him and he lost control, smashing through the cafe front. Falling out the cab, he’d crawled behind the counter, miserably hiding in the shadows for the day. Since then, Hillary always comes along. It’s one o’clock. No sign of the barge. ‘Did you radio in my medicine?’ ‘Sure, you really need that stuff?’ ‘It’s Frank, he scares me. It’s difficult, you and me.’ So that’s his name, French remembers now. They watch the river, the moonlight sparkling off the still high tide. He checks his watch. They’re late. The night is cold and crisp, the wind having dropped some time ago. After thirty minutes, he fetches the radio from the cab. There’s no answer. He changes channel; nothing. Eventually they hear a voice. It goes dead again. ‘You hear that?’ ‘A cry for help, something…’ French looks at the small dinghy sitting upright in the trailer. He has it just in case the river breaks its banks and completely floods the road below. That had happened once and he’d been forced to use it, abandoning the tractor until the next low tide at night. Hillary senses what’s in his mind, then feels dread when he asks the question: ‘Shall we risk it?’ ‘They’ll shoot on sight.’ ‘The motor’s fast and the barge slow. If we see its light, we’ll turn and scarper back.’ The dinghy slides down the slipway and splashes in the water. They look into each other’s eyes. ‘It’s risky.’ ‘I know.’ As he pulls the starter cord, their hearts beat with fear. The whirring motor breaks the silence; anyone around can hear that, he thinks. If only he’d brought his gun. Out of the Zone the air feels cold and fresh; it bites their faces. Savouring the new air, it helps to ease their tension. Not speaking, they focus on the way ahead, the dinghy gently bumping on the moonlit river. Leaving the river, they turn into the canal through a dismantled lock. Way ahead, they see the sombre shape of the moored barge. ‘I don’t like this,’ whispers Hillary. Neither does French, but he doesn’t say, just puts a finger to his lips. He cuts the motor, silently drifting in towards the barge. Scraping along its edge the dinghy comes to a stop. They climb aboard. Standing in the darkest shadows behind the wheel house, they wait. Not a sound or any sign of life. The barge is loaded for the drop. ‘Let’s look around a bit,’ he says softly. There’s nothing on the barge except boxes. In the moonlight, across the road, a guard house shows. Behind that is a track leading up to the garrison on hill. Hillary pulls his arm. ‘I’m not going up that hill.’ ‘No chance of that, just the guard house, let’s make it quick.’ He grabs her hand. On the road lie two dead soldiers. The guard house door is open. They hear choking. French picks up one of the soldier’s rifle and peers inside. Unable to see much, he takes his flashlight and illuminates the room. A soldier’s lying on the floor, head propped up against a wall, a radio in his hand; he’s vomited, bathed in sweat and gasping for breath. ‘He’s got the virus, just look at him, won’t last the night,’ Hillary whispers to French’s ear. ‘Leave him. Let’s take some food and go.’ He’s about to leave when she stands in his way and stops him. ‘Going to tell you last night,’ Hillary exclaims, suddenly unconcerned about making noise. ‘Do you ever feel ill or out of sorts?’ Puzzled, French shakes his head. ‘Only ones left alive are those who ate the scallops last February, don’t you see, they’re a cure.’ ‘I only ate them once.’ ‘Vicar worked it out, thinks the radiation and the virus got into the scallops and…’ ‘Made a super virus, which we’re full of now?’ ‘Something…it’s the season, might save his life.’ He looks at the dying soldier. ‘There’s only way to find out – grab his feet.’ Cold wind rushes over them as the dinghy moves along the river towards the town. Over the whirr of the motor, the wretched rasping of the soldier’s breath distracts them. French speaks: ‘If the virus doesn’t get him before the night’s out, radiation will.’ With the tide receding fast, the river’s low. They look across and up to the shadow of the tractor, now high up on the riverbank. ‘Tide’s too low, never get him up the jetty ladder,’ Hillary says. ‘Damn, never thought of that.’ ‘Can’t use the slipway in town, I need to get the scallops from the clubhouse, besides…he’s a soldier.’ She’s right, he thinks; the town would surly lynch him. Briefly imagining a depraved medieval ritual behind the church, he then recalls his own lucky escape from the hands of an angry mob. On the edge of town, before the rail bridge, French realises that soon the whole of Rye will hear the dinghy. The dinghy means no food drop: questions will be asked. But first he needs to hide the soldier. Full of apprehension, they don’t speak until arriving at harbour jetty, two miles further downstream. French looks at the vertical ladder of the jetty: it must be twenty feet from the water to the top. Pulling alongside the harbour master’s boat, Hillary ties the dinghy tight. The engineer had decided to keep this boat running; he too needing purpose in his life. But no one’s ever used it. Heaving and pushing, they get the soldier on the deck. The rough handling stirs him. Panicking, he makes a failed attempt to stand. Shaking on the deck, blurred eyes staring into space, he tries to speak before falling limp again. ‘Delirious, near the end,’ French mumbles, turning towards Hillary. But she’s already up the ladder. Leaving the soldier, French enters the wheelhouse and goes below. He closes all the porthole shutters. Back on deck, the moonlight shows the rifle lying in the dinghy. Not wanting to rouse suspicion, he leans over the side and grabs it. He slings it in the cabin. Standing in the wheel house to abate the cold, he notices the lights are out on the Fairlight coastguard mast. He has to tell the town’s people the truth about the food drop but has no idea what to do about the soldier. ‘Here, let’s get started.’ Hillary stands at the wheelhouse door, holding a bowl full of scallops. They look at the soldier, motionless, his failing breath weaker by the minute. ‘He’ll never get them down.’ Hillary has an idea. They prop the soldier up against the side of the boat. With one hand, French holds the soldier; with the other, he holds the man’s jaw and opens his mouth. Flattening down the man’s tongue with her fingers, Hillary forces small pieces of scallop down his throat. Soon crammed full, his airway blocked, she quickly realises his shallow breathing’s stopped. ‘He can’t swallow, we’re killing him,’ she says. French shrugs, resigned. ‘Wake him up, do something!’ Hillary yells. French violently shakes the soldier before pulling a box of matches from his pocket. He strikes a match and holds the flame close to the soldier’s little finger. There’s a dreadful gurgle followed by a tiny gasp. French slaps the soldier hard while Hillary repeats the feeding process. A small throat reflux takes some scallop down. ‘How many is that now?’ ‘About four pieces, how many did you eat last year?’ ‘The whole bowl of course, near starved.’ With daylight coming soon, they hastily move the soldier down into the cabin. French leaves his torch in the soldier’s hand and writes a note, sticking it to the inside of the door: “You’re safe. Don’t go out in daylight and keep silent. Back later.” He locks the door. ‘I’ll tell Frank the barge didn’t show and nothing from the radio. That’s all.’ He nods and they embrace. He watches her hurry across the greens in the last shadows of the night. Looking to the east, the stars are fading, the night sky turning blue. He picks up the bowl of scallops and climbs the ladder. On his quick dash back to the harbour office, he hears a noise. Is that the soldier retching? There’s no way he can find out now. Dog tired and needing rest, he stares at the scallops sitting on the console. What if the vicar’s right? With a mixture of hunger, hope and superstition, he eats the lot. He wakes to a loud banging on the door. Spooked, French sits bolt upright. He hears his name. Hillary stands there, distraught. In the morning twilight, he glimpses her black eye before she flings her arms around him. As he holds her, he looks out the open door and up the river at the flashing harbour lights. ‘Mrs. Johnson slapped the vicar’s face, said it was your fault. Told on us, how could he?’ Good for Mrs. Johnson, that bastard needed slapping, French fumes. ‘Frank’s so angry, the only reason they haven’t come for you is because of that.’ She points towards the gun, hidden in the darkness. He has visions of his own demise on a funeral pyre behind the church. ‘We need to leave. The roads are blocked and the only way out is by boat. You know how to handle a boat, yes?’ ‘I’m a fisherman’s wife!’ Hillary leaves to collect a few belongings and French rapidly dresses, stuffing the gun in his coat pocket before heading to the boat. In the high tide, it’s only a few ladder rungs to the boat. He jumps on deck. He’s never shot his gun outside of training and knows he doesn’t have that killer instinct. Standing in the wheelhouse, studying the boat’s control panel in the faint moonlight, he can’t even switch it on. Come on Hillary, you’re needed here. And then he sees the cabin door. It feels too much to deal with right now but he turns the lock anyway, pulling the door wide open. The torch turns on, shining directly in his eyes. The rifle’s red spotter light clearly on his chest. ‘Don’t shoot, I gave you medicine, brought you here,’ French desperately blurts out. There’s a terrifying pause before the spotter light turns off. French’s heart beats hard. ‘It’s safe, come on.’ French slowly backs away. He’s dealing with a soldier whose orders are to shoot anyone from Rye on sight. The soldier appears, following French onto the deck, the rifle still pointing at his chest. French raises his hands. The torch turns off. As the soldier adjusts to the darkness, he asks: ‘Where am I?’ ‘In the Zone.’ ‘Rye, the radiation will kill me, I’m not safe.’ There’s total shock in the soldier’s voice. ‘The medicine cures that too.’ ‘Medicine?’ ‘You had the last dose,’ French says, trying to get the soldier to lower his gun. Frank could be here any minute. The soldier sits down on a box and lays the rifle across his legs, finger still around the trigger. ‘Is it safe for us out there?’ French points towards the sea. ‘Safe? No one’s there, all dead, I think.’ French studies the soldier. He can’t be more than twenty and now looks fit and well. There’s no time for questions but French needs to know: ‘What happened…changed?’ ‘Rye happened. You made a super-virus, wiped out the entire country, world, I don’t know…’ He shakes his head and, with a lost look of fear, looks up at French. ‘Am I cured?’ French feels he’s already wasted too much time. ‘Some dangerous men are coming for me, we need to get to sea. You’re a soldier, stay out of sight.’ He points to the cabin door and then ascends the ladder. Hillary is there with two large bags. ‘He’s awake, in the cabin, be nice, his finger’s still on the trigger.’ At the top of the harbour office stairs, he shouts over: ‘Be a minute, start the engine, I’ll dig out some of the harbour master’s sunglasses.’ Stuffing bags with anything useful that quickly comes to hand, French hears the roar of diesel trucks racing on the road. He knows some of them have headlights. Too nervous to stuff the last bag, he leaves it, hurrying down the stairs, trying to ignore the sound of his impending doom. But he’s too late. The trucks skid to a halt, headlights illuminating the jetty. Before he reaches the ladder, Frank’s voice bellows out: ‘Stop or I’ll shoot.’ Knowing they have shotguns, he stops and turns. Dazzled by the lights, he can just make out four trucks and the shadowed shapes of men. The sound of the boat is two big strides and a leap away. He would never make it. Standing there, holding a bag in each hand, his gun’s out of reach in his pocket. It wouldn’t be much use anyway, not against this lot. ‘Thought I wouldn’t find out, you rat, she may be a scrawny good for nothing but she’s still my wife. Got plans for you French. Vicar wants to see you up behind the church.’ Frank moves closer to him. So this is how it ends: Guy Fawkes behind the church. Dazed and resigned, he doesn’t hear what’s said, but sees it clearly: the red spotter light cutting through the night. It stops at Frank’s chest. Frank looks down. The soldier orders French to get on board. Throwing his bags on deck, he downs the ladder and unties the mooring ropes. The soldier, on the wheelhouse roof, shouts to Hillary. She leaves the jetty, steering the boat fast towards the river mouth. Slowing the boat to bounce across the sand-bar surf at the harbour’s mouth, Hillary turns to look back: no one’s followed them along the riverbank track and there’s not a boat in sight. The soldier drops down on deck. All he wants to know is if he’s cured, and all French needs, is to know that the morning light is safe. Both convinced, they join Hillary at the helm. ‘Says we can see the sunrise.’ ‘Anywhere special in mind?’ Hillary asks. Perplexed, French stares into the darkness, then at Hillary. She meets his gaze and bursts out laughing.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed