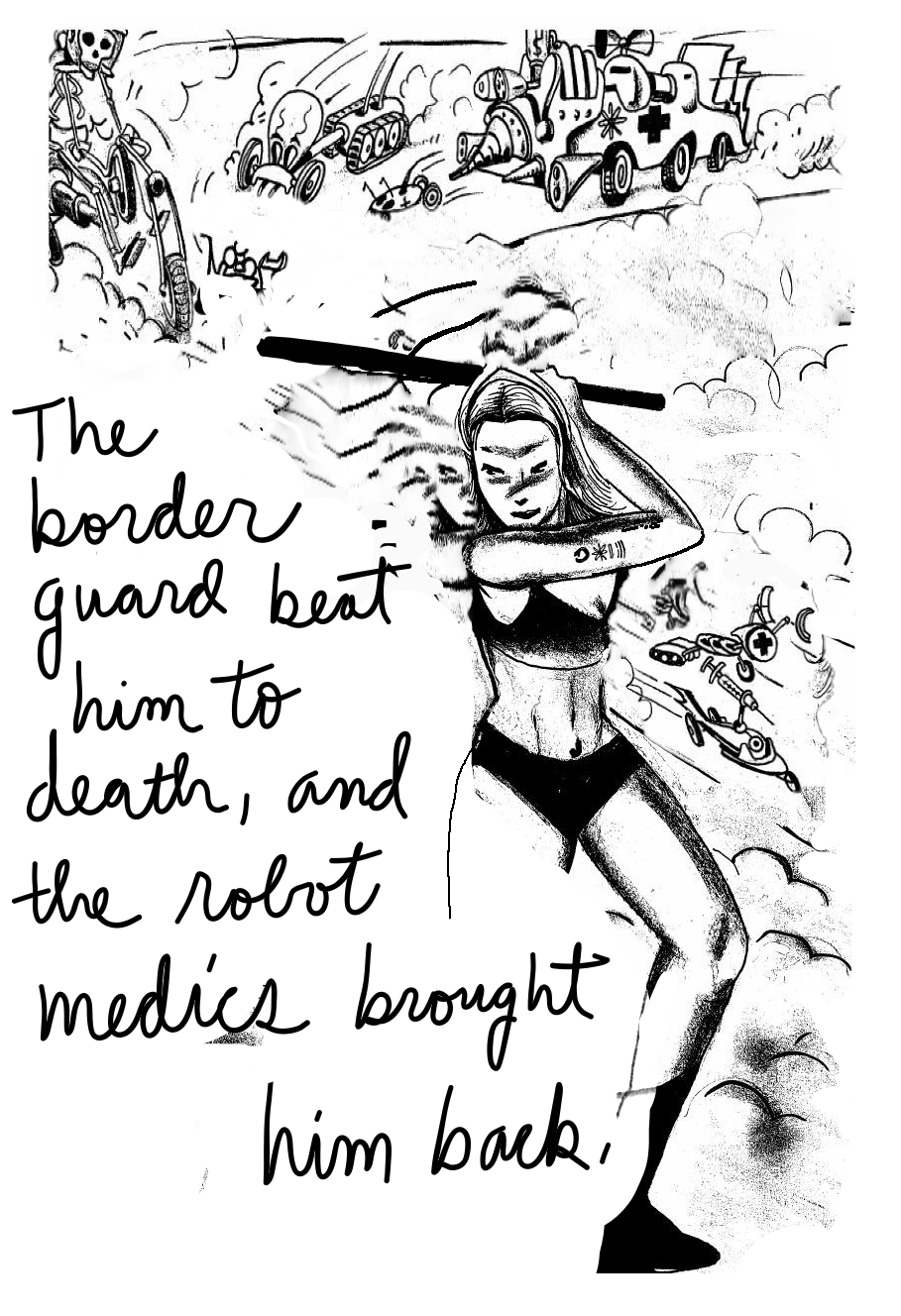

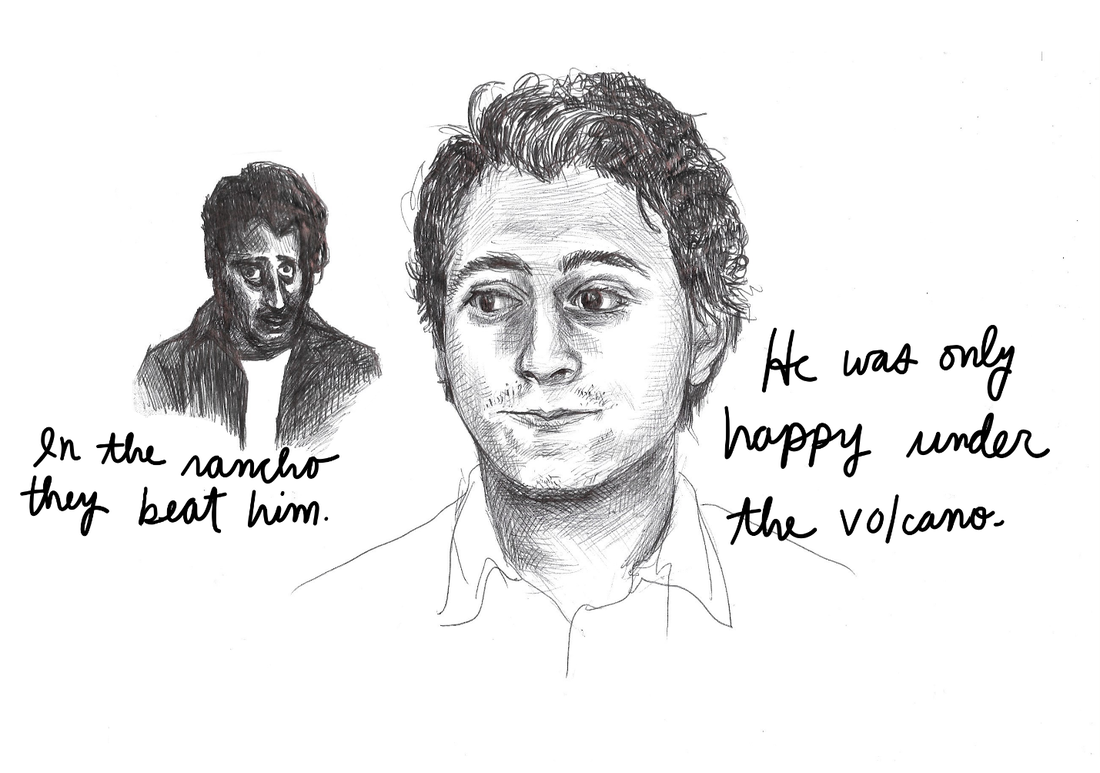

Gregg Williard grew up in Columbus, Ohio and attended the Columbus College of Art and Design, The New York Studio School and the State University of New York. His work has been published, most recently, in Muse/A, X-R-A-Y Journal and Raleigh Review, among others. He lives and works in Madison, Wisconsin and teaches ESL to refugees. His spoken word radio show, "Fiction Jones" is broadcast on WORT community radio (wortfm.org). (SELF-PAINTED PORTRAIT) Hector X1. Mordidas The birds told him he was no cop. A beat-up Toyota van with U.S. plates tore by him up the mountain. He hit the siren and followed, one last time. Around the first bend the van pulled over in the brush. When he was twenty feet away it suddenly lit out and roared off. Hector was stunned. Motorists never ran away, unless he’d accidentally picked an untouchable – a cartel member or politico – in which case he’d quickly realize his error and give up the ghost. But untouchables didn’t drive old Toyotas and look like tourists. They surely wouldn’t be wasting their time in this barren part of the mountains. And they weren’t slowing down. The road narrowed to the climb. Around a corner they stopped again. Two crows circled low and started cawing wild. He killed the siren and waited, watching the birds and hoping the van would leave. He’d decided not to follow anymore. There was no movement from the van. He got out, and dust kicked up around him and his ears rang with gunshots. He tumbled back into the car and the windshield exploded over his head. “Oh, Jesus! Hey! I’m not really the police!” How did glass get in his mouth? After a few seconds he heard high pitched laughter. “Just throw your gun out and we’ll let you go your way.” “Yes!” A higher voice said. “Go your way!” Hector threw out his gun. A thick man with a beard and a white shirt got out of the van. He was followed by a smaller man with shades and an assault rifle. The thick man scooped up Hector’s gun, checked the clip and motioned for his partner to follow. Hector’s bowels heaved. Twenty feet from his car the thick guy stumbled. All at once three of the ravens were on his head. Another two fell on the other man. More came, wings beating blood and pink flecks into the air. The men bellowed and shrieked and flailed at the birds. Tufts of black hair, bird or human, garnished the dusty road. One of the birds lay broken on the ground. Others joined the melee. It was over in seconds. The birds ignored Hector, busy with the men’s faces, pecking and pulling at pink ribbons of sinew as he walked shakily to the van. On the seat was another gun with a full clip. He snapped it in his holster and was about to return to his car when he saw a little figure on the dashboard. It was one of his Calaveras dolls, the one that looked like a Moby rave D.J. with a little turn table and light stick. He pulled it off the dashboard, put it in his pocket and returned to his car. His cell phone was on the floor undamaged and he called in a report. He watched the birds, and could smell a coming storm. The birds left the bodies and circled around Hector, swooping low and crying out. Then they lined each side of the path and watched him. They were very still. 2. Hector X Growing up in the ranchita there were daily beatings by the kids in the village. Hector’s mother would wipe off her bloodied son and ask his sister Luna why all the kids picked on him. She usually just shrugged but once managed, “’Cause they know about him, mom.” “Know what?” She just shrugged again. Hector kept quiet. Hector wrote an X for his name. You felt lucky if he gave you a blank smile, or a grunt. He cut sugarcane with hate. He drove his uncle’s poultry truck when he was barely tall enough to see over the steering wheel. He didn’t read, write, talk or understand clocks. Despite his reputation as a dullard, he was the only one who could pop the clutch just right, jerk the heap up out of ditches and mud and stalls. He mumbled once, lucky with junk. It didn’t mean anything. No one argued. Over time Hector perfected the guise of silence into a wary languor, then an impenetrable armor. His tormentors fell away from boredom; his exasperating indifference made beating him as satisfying as torturing a brick. His stealth reached the heights of art. He defied physics into invisibility, achieving an absence of mass. The silent one in the shadows. Eating shadows, made of shadows, all the while plain and simple as anything, or nothing. But if you looked closer he wasn’t there. Not just nobody special, or nobody normal. Nobody nothing. When he started to read and write it was everything, in English and Spanish, things he shouldn’t have understood, and all at once. He hid the books. At night in secret he went to the shed to read and make tiny Calaveras sculptures by lamp light from clay, and scraps of wood, wire and junk. The skeletons were in various contemporary settings, such as tiny health clubs, or office cubicles with computers. He gave them to his cousin to sell at the local market, and they split the profits. He still signed all his work with an X. His uncle Armando became a big man with connections. He said he wanted to help Hector’s family, and gave his mother money. Hector was allowed to leave the fields and work on his sculptures. When Hector was twenty-two Armando offered him a big chance as a traffic cop. The job came with a squad car and siren, and a black uniform, with a black leather holster and a black gun. Hector dreaded it, but to refuse would have aroused the suspicion of others, so he agreed. If he brought in his share of bribes (mordidas, “bites”), left the local cartel and gang alone, kept his uniform clean and his boots polished, there was a sure road to advancement. He could finally move off the stinking farm, help his mother, keep his sister out of the maquiladoras and maybe be able to afford a nice woman or two for himself. When Hector balked, Uncle Armando winked and said, “El que no transa, no avanca.” (He who doesn’t sell out, doesn’t get ahead). For a few weeks Hector dutifully wrote tickets and took the bribes, but it was too embarrassing, and he ended up in the empty foothills of the volcano, at a favorite spot up the road where three big boulders made a circle as if gathered for a story. He would sit on the big flat one in the middle and scratch skeletons and X’s into the rock. He shot at but missed ravens, crows, and sunning iguanas. He watched ants, running in and out of their tiny rooms like the bed-hopping characters of his mother’s daily telenovelas. He worked on his Calaveras models. Slowly he gathered an audience of ravens and crows. They sat inches from him to preen each other and coo. The bigger ravens liked to lie down on the ground, right on top of the streaming ants, splayed out like sunbathers at the beach, their beaks pointed straight at the sun. They understood, before Hector did, that he could never shoot them. Their caws and dak-daks began to sound like well-meant advice. He’d take it, when he understood what it was. After the birds attacked he drove home in a trance, slowing to toss the dead man’s gun out the window and into the brush. He pulled off the road and parked his car behind some rocks at the entrance to his mom’s farm. Still dazed he sat down to gather his thoughts, but behind a bush he discovered a body, clothed only in a pair of pristine jeans. They’d been pulled down to the knees. The corpse’s ass hole was jammed with a square plastic bag. Hector tugged it free. It was a brick of cocaine. He pushed the bag back in and cleaned his hands with dirt. He reported the body, and the police came and took it away. No one mentioned the bag. There were a lot of questions about the mangled men on the mountain road, and the birds. But no one talked about the body, or the drugs. Hector kept his head down. He quit the force and went back to the sugar cane, making his wood and clay skeleton models at night in the shed, and reading. He returned to the mountain and sat by the curve in the road waiting for the ravens, but they ignored him now, silently gliding over him, high and serene. Maybe they didn’t know him without his uniform. He felt bereft. Then a bad looking guy began asking his cousin questions about the figures, and Hector told his cousin, Julio, to stop selling them for a while. Hector kept on making them at night. He did a whole series of skeleton policemen in gunfights, and bad guy skeletons being set upon by ravens. He made the birds with paperclips and his own hair. On a visit to the dumpsters behind the factory he brought back a bonanza of old circuit boards, and created a new line of robot Calaveras, half skeleton, half cyborg. He decided to put them on sale again, and boxed them up for Julio. On a moonless night as he locked the shed he was struck from behind. He shrank into a fetal crouch, as he’d done many times before. He tried to cover his head, but they kicked at it, paid special attention to his head, and his ribs. And the box of his sculptures. He heard the crunch and snap of the skeletons, and his own bones. When they were finished and gone he passed out. He couldn’t remember how he got there but he woke on his kitchen floor. The door to the house was kicked in, and when he dragged through the house his mother and sister were gone. All the lights were on, and the house was trashed. His mother’s purse was still on the bed. She would have never left on her own without taking it. He called his uncle Armando for help. Armando promised to come over but Hector passed out again and didn’t see him until he came to in the morning. Armando said, “You a mess.” Armando helped him to his truck and drove him to the police station, where Hector’s former captain told him there would be a full investigation and search. But first, he said, there was the matter of the drugs. Hector had trouble sitting up, and breathing. He said he knew nothing about the drugs. He had called the police and they’d taken them, and the body, away. Everyone knew that. But what we don’t know, the captain said, is what happened to that kilo of coke? Hector looked from his uncle to the captain and back again, searching for help, then sense. Their eyes were a blank, hard show, the eyes of bad movie actors. Hector understood the drugs had been stolen, and he was to be blamed. The captain told Armando to leave the room. When they were alone he said, “Your mother and sister are fine. They had to leave for their own safety. When we recover the drugs we can get you to the doctor, then bring tu madre y tu hermano back to you. You’ll all be happy again. You’d like that, wouldn’t you? For their sake, tell us where the drugs are.” “I hurt.” “You think this is hurt?” The captain took his stick and poked Hector in the side. The pain put Hector on his knees. “Why did you quit the force, motherfucker? Did you think you’d be all set for life now, once you cut that dope and put it on the street? Did you? But you couldn’t have moved it all so fast. Where have you hidden it?” There were more pokes, then blows. Hector went invisible, and gone. He passed out, then came to. Then out. For a long time he looked out from the stone floor of a cell that dipped into a rusty drain. Then the floor was swept with shadows like brooms. The drain glowed like pearl, turned to brass, bronze, gold. Birds were casting the shadows. His ravens were back. We like you in black. Crooooaak croooaak. We’ll help you. Gronk-gronk. Come back to the mountain in black. Tok Tok Tok. In uniform, now! Don’t Wait! Wonk wonk. A metal door slamming in the distance. He woke splayed on a bare mattress that smelled like sweat. His shirt was gone and he was wrapped in bandages over his ribs. He had to roll to sit up and flipped off the bed, but found a position on his side on the floor where he was able to breathe. Across the cell was the captain. He asked Hector if he was ready to talk. “Don’t thank me for getting you patched up. I have a big heart.” Hector leaned back against the bed frame and took ragged breaths until the pain eased. Oh, sorry,” the captain said. “I forgot. Usted es el gran silencio Senor! Big Mister Silence. Use sign language, asshole. Tell me about the coke.” “Where’s my uncle Armando? He’s the one that knows.” “Now you’re turning on tu querido Armando? He’s the only reason you’re not dead now, Hectorlito. Leave him out of this.” “I’ll take you to the drugs. I buried them. Up the mountain. You give me back my uniform, and my gun, and car. I’ll drive there and you follow me.” The captain spit on him and laughed. “Why should I do that?” The gob of spit sat on Hector’s leg. “You want the drugs.” “You are a crazy fucked piece of shit, but all right.” The captain left, and returned with a uniform, boots and a gun. He tossed the bundle on the bed. “It’s unloaded, Officer Asshole.” “I don’t need bullets.” The captain shook his head and laughed. “You’re going to wish you had one for yourself if this doesn’t go right.” 3. Another Murder of Crows Had there been a landslide? The road shrank to a trail, a path, a trace, a chance. It was too narrow to turn, too late to turn back. On his way to certain death the crunch of shards and scree, the churn of dirt stirred to dirge Hector’s shift to first. This would be his dust keen. But why wait for a hymn? He stepped on it, sped the droning road to whine. The captain and his two men, Beto and a guy he didn’t know with an expensive haircut, kept up fine. Hector barely recognized the way; it looked taken over by the mountain and the wind. But they wound their way there, to the turnaround with the three big boulders. Hector parked and opened the door to reach down for a bit of gravel. He took off his hat and marked the top of it with an X drawn with the chalky stone. He pulled the hat back on his head tight. Hector told the captain and his men the drugs were buried behind the big middle boulder, and the captain dropped a shovel at his feet and told him to get to it. Hector took the shovel and made a show of triangulating off shadow and stone, pacing out a secret find not there while the men looked for shade, lit up cigarettes and passed a sweating bottle of Corona. Beto sang an army song about Juan’s sister. The nameless guy drank and smoked and flipped through his phone, looking cool. 4. The Exact Location of Nothing Hector finally settled on the exact location of nothing. The shovel edge glanced off a skosh of gravel. The captain spat and barked for Hector to get serious. Hector’s side was agony but he leaned in and thrust deep just as the first shadow streaked over the ground. The raven returned to dip and hover just over Beto’s head, casting a dash of shadow on his shoulder and doing a dagger dance of shadow around his feet. Another bird, a smaller crow, came straight out of the sun so it was almost not there at all, silent and almost motionless. All three cops blinked into the sky and stepped back. They drew their guns. The captain had heard the story of the cartel men torn apart by birds. He aimed his gun at Hector. “Keep digging or you’re dead.” Hector stabbed at the ground, drenched in sweat and his slick hands frozen afraid and sliding into splinter. Maybe he really had found the drugs. They’d been taken, hidden, so why not here? There were miracles. Juan Diego had bumped into the Virgin of Guadalupe just walking down the road. He’d told her no one would believe him, that she needed to appear to someone who mattered, the story went. He said, I’m nothing but a back frame, a tail, a wing, a man of no importance. But The Virgin insisted, he was the one! His mother loved telling him that shit. The takeaway for Hector was always that line in the story; I’m nothing but a back frame, a tail, a wing, a man of no consequence. A back frame. What did that mean, exactly? The back of a picture? The blank canvas, the stretcher strips? I’m nothing but… “Dig, asshole!” Then the rest of the birds fell in a thumping black rain, like stories from the Bible of black things out of the sky that didn’t belong. Giant locusts. Dead things. Shoes or bloody keys or hailstones of mud, and hair. No. dead birds. They hit the ground dead atop the ants again. Hector almost screamed, this is no time to sunbathe! But then they sprang aloft, not dead. But silent. An un-death sort of life, flailing, raking wild, all in silence save the flapping in fever air. He’d never seen so many ravens, or crows, rooks, black birds, whatever they were, soundless, and with eyes too bright, with the glow of black-light LED’s. The scribble cloud of them ensnared the cops. The captain and Beto got off some rounds and killed some of them, but they just kept coming. He couldn’t see the nameless guy. Hector watched it all from behind the boulder, on his stomach, pressed into the ground. First he covered his head, but the birds paid no attention to him at all. They closed around the cops, the captain and Beto quickly on the ground, covered in black feathers and blur of wings. And in the center was the first bird, the largest crow he’d ever seen, and white, its amber beak cocked up out of the melee, bright red and busy with gristle. What yanking ardor! Hector waited on the ground until the flapping and the screams were over. When he opened his eyes the birds were gone and Beto and the captain were laid out and dusted like floured meat, their heads, faces, hands pecked and poked and pocked. It was even worse than the first time, with the bad guys up the mountain. This was more like when he’d once seen a neighbor emptying a shotgun into a rabid dog, at avid close range, over and over. The captain and Beto’s uniforms were pin-holed to a delicate shred, like doilies of black lace. Hector followed a blood trail soaking into the dust, black as chocolate sauce. He found the nameless guy hanging half out of the squad car, empty eye sockets blank and cool like beady shades from an ‘80’s action film. If he raised his head just above the ground and let his gaze climb the mountain, there was nothing here to upset the silence, parched to pure. But he had to move. Soon there’d be more police. And his uncle. Tio Armando was ambitious. His absent father’s brother, always after Hector’s mother. The big man of the ranchita. He’d been north and come back even bigger. He always talked big plans for Hector. Why this set-up, Hector couldn’t say. It was all so stupid. All Hector ever wanted was to be left alone, here in the mountains would be fine, make his Calavera sculptures and dream bigger than the USA, bigger than the world. His side hurt bad. He couldn’t breathe without pain, and his head was splitting open. Move. Find his mom, and Luna. And his cousin. Julio had friends in Corpus Christi, Santa Fe, and Las Cruces. He said they could make a living there selling Hector’s shit at fairs. Authentic folk art. Not the robot shit, man. Keep it in the barrio. Skeleton mama rolling out tortillas, Skeleton Luna smoking while teasing out a quiff. Skeleton Cop Hector collecting bites. No, don’t go there. But Hector didn’t listen. He’d make what he’d make. If he could ever get his family back. Get back to his shed. Move. But he could only ease to the ground and clutch his pounding head. He couldn’t, he wasn’t going to get out of this. He wasn’t smart. He wasn’t anybody. Mister back frame. His uncle had set up the right guy. He knew Hector could never do anything about it, and nobody would stick up for him because he was weird and he didn’t make sense to anyone and Hector never knew what to say to anyone else or how to fight back. His mother had never given up trying to tell him nothing was wrong or different about him. His only problem was the silly stories he told himself. All he needed was to look into the mirror. He’d see a person, a little bit demon and a little bit angel like anybody else, but with a little more angel than most. Hector didn’t know about that, and he was afraid to tell his mother that sometimes when he looked in the mirror, he didn’t recognize the guy he saw there at all. And sometimes, less often but sometimes, vampire-like, there was no one and nothing in the mirror. Then su extrana hermana Luna would walk by. The mirror showed her fine, always with a knife and a cigarette. The blade and the burn had scarred her shoulders twin croix de guerre of gang pain games over santa muerte tats, the left one chomping some blond chica vamp with glee, the right hard to untangle. Luna was the real one, the only one in the mirror. That was the best sight of all. Like getting dressed up, cholo invisible man style, each set of clothes—the Dickies plain tee, the flannel Pendleton, the Ben Davis Gorilla Cut Khakis one size big in the waist, the black Lugz shoes, the hyna tat—all conferring one more pixel bit of see-through to nobody home, vato, but the girl. Just a see through to Luna, and that was fine. She was the real one in the mirror. His last chance to be real, vato. Move. 5. Eating Crow He tottered to his feet. Brambles cracked under his boots in a stagger to the car. The pain clawed back at his spine, sent it into a twist, and he saw his own body mirrored back across the road and over the plain in a giant maguey plant of grey green, gnarled tentacles, overgrown and knotted into surrounding tufts of mesquite and nopales cactus, like a collar of green steel wool drawn up against the wind. He was dreaming on his feet. The foliage made serpent moves and a fan dance shiver. White fog billowed around his ankles. A rush of wings and then silence behind told him he’d been abandoned by the birds. The sky darkened. He heard crunching footsteps and turned. Before him was six foot tall woman in a red and gold bikini and a red and gold tiara, her height amplified by a piled up hair-do, white and gold high heel go-go boots and an expression of regal disdain that sharpened to menace as she stepped forward. She held out a thick staff toward his chest and hissed a foreign command. Hector backed away and put up his hands but the woman kept coming. Another stick! He grabbed for his gun, holding it out and then flinging it into the air in a show of goodwill. Hector saw over the woman’s shoulder gold spires and domes of a futuristic city, sparkling out of distant clouds. Drone-like vehicles buzzed through its arches and sky walkways. Her super city home! He felt a glow of peace and looked back at the woman, who glared down at Hector’s gun and then back at his face with loathing and rage. The stick came down on Hector’s shoulder and arm and he stumbled, trying to shield his face and head. But his broken ribs constricted his reach and he could only crouch down and take the next blow with his head, and back. Staggering he took another blow and another, on the ground and full in the face, before a black-out plunge into white freezing cloud shut him down. With his other senses off, his hearing stayed acutely tuned to every nuance, from the meaty thunk of the baton splitting and smashing his skull to the bright crack of bone, blubber of blood and splong of popped eye balls. His dying senses set off a gurgling twang, like guitar strings snapping under water. Behind it was an acid yellow sonic undercoat of trill, whoop and yowl—emergency sirens climbing up the mountain, to him. Though his eyeballs seemed to be dangling loose on distended threads of muscle his vision returned with the wails, and he could see the woman again, and an approaching parade of silver vehicles coming out of the fog and dust. Even as her blows rained down tenderness stole her face. Her baton dropped. She disappeared behind the huddle of ambulance machines, brilliant silver robot pods and chassis on treads, jostling like eager rubes for the best view of the geek. They shivered and gawked over him on spindly spoked tires, insect legs and unicycles gyro-ing balance in weaving sway. Silver skeleton drivers purred from within and scanned through the settling dust. A fat hologram Red Cross detached from one skeleton’s forehead and floated over Hector’s body, bathing him in scarlet light. Hector was flat-lining, but with potential. The Red Cross hopped back onto the skull, and green tinted canopies in the vehicles hissed open and issued arrays of surgical automata on a synthetic-scented breeze. Defibrillator probes zapped, and there was a beat. He was massaged by whining articulations of white plastic and silver metal, coddled and trussed in magnetic suspension harnesses, shot up by syringe-tipped tentacles and sliced open by laser scalpels glowing white, and blue. Delicate gold mandibles coaxed battered skin, and tongs spread the smoking incisions wide. Vacuum snouts chortling like the suck of draining straws suctioned blood and bone debris clear. Pearl polymer hands of nine fingers with six digits each tucked bladdered implants, and coaxed amber prosthetics deep into Hector’s now semi-corpse, reassembling and fusing shattered bone with synthetics. Squashed organs were replaced with animal-human hybrids, vat bred tissues, or all-machine pods. Then beetle surgeons cauterized, and spider web spray staunched, with platelet powder sealing it all in a pixie-dust puff. The machines rinsed off the remaining blood, viscera and dust from Hector, and then from their own instruments and the surfaces of the medical mobiles. Defibrillator implants chimed and found their rhythm. Hector gasped, coughed, and breathed, slow and easy. The bustle of digital alacrity stilled, and all was a sparkling, humming sheen. He was taken to the city and, after a brief recuperation, toured its many attractions outfitted in a powder blue jumpsuit with white boots. He was guided amiably by the tall blond woman who had beaten him to death and back. Her name was Xandra. In this cloud city Hector floated on a pain-free cloud. There was relief, but without the wrenching pain there was also a nakedness that let in doubts like a draft. He had known them all his life, but now he could not bury himself under blankets of silence and evasion. He walked through the streets as if freshly flayed. Before this, he would never have asked Xandra why she beat him so mercilessly. But now he interrupted a tour of the marketplace of floating fruit to ask, “Why did you hit me over and over?” Xandra kept walking. She said, “You will observe that our fruit is not only delicious and colorful, but performs gay dances in the air. Each succulent follows a different pattern, and rhythm. Similar species fly in groups, while unlike varieties trade off, mirror, counterpoint, or even collide. We try to minimize this to avoid a rain of juice and pulp falling on the shoppers below.” Hector tried to attend to the spirit of the tour. “What happens after these flying fruits have been ingested?” “Look, look there. The purple and orange ones, like your gourds? Do you see how they have been sliced open, how the pink flesh has been exposed? How the insides pucker and swell? Now, watch!” Hector saw the gourds aim at some bright yellow and pink grapes that had been pelting the crowd below. The gourds expelled a blast of black seeds that sent the grapes scampering into the breeze. The crowd around them approved with claps of barely glancing palms, and smiles directed shyly to the ground. They all had the same regal, demure airs and brightly colored clothes as Xandra. This place was truly, as he had heard people say of the States, a “shining city on the hill.” Though perhaps, also like the States, with the name bearing a double-edge: shining and smiling, but unable or unwilling to answer the darker questions that had to be answered before anything more could happen. He felt possessed by questions: Why did you beat me with the stick, when I’d thrown down my gun and never meant you or anyone any harm? Where are my mother and sister? Why did the birds rescue me? Why did the robot doctors heal me? Why them, when my own mother and sister never did? What is this place? Why did you bring me here? Is this the future, or am I dead, or both? What is wrong with me? Why can’t I talk to people? Why can’t I find someone to love? Or, why don’t I seem to want to find someone to love? Why do other people look at me, and look away? Xandra prattled on, her feline contralto lilting with patrician flourish. Amidst the continuing wonders of the cloud city, (a fountain of singing flames, zipping drone food carts of quivering flan, mariachi-spouting spiders weaving bridal gowns, children with heads of exploding volcanoes, marching lines of flagellants on cell phones,) Hector’s thoughts hammered inside his refurbished skull, the ghost of his new machine ragging his digitized meat with the moans of spectral, and earthly, fears: Why is my only time of peace late at night, making little skeletons in the tool shed, by the light of a battery lamp? Or with the birds who shared the sun and the mountain silence with me alone? What is wrong with the shadows I cast? Why does my reflection in mirrors smell like burning roses? What is wrong with this place? With all places? The crowd gave out a cry as giant balloon heads of Frida Kahlo, Diego Riviera, Posada skulls, the Virgin of Guadalupe, Santo, Dracula, Frankenstein, The Blue Demon and Santa Muerte, Santa Claus and La Llorana. Xandra joined the cheers and then stopped before a local artisan sitting behind a stand of incense, votive candles and Milagros charms. “Ernesto,” she said to the man, “would you kindly show our visitor from the other side – el otro lado – how the true flames burn in Nepantlia?” Nepantlia. The in-between town. But before Hector could ask for an explanation, Ernesto growled, “I will not” and crossed his arms, glaring. He stared down some black hole event horizon of hate beyond hate. It seemed to Hector that Ernesto would be pleased to dump the pair of them into that mortar of a vortex to be pestled into graviton powder. Hector had a moment of longing for that very fate. Then shuddered in perplexity: “A mortar of a vortex to be pestled into graviton powder”? How had he come up with that? Ernesto was probably in his thirties but his face was much older, sun-dried purple and criss-crossed with white scars. A face out of a sugarcane gang. His futuristic jumpsuit was wrinkled and stained with betel juice. Maybe he could help find Luna and his mother. Hector had been hoping for a fire inside himself, a new sense of mission for justice and revenge. Saving his family would redeem his life in one act of valor. A destiny, at last! A story! But he wasn’t going to do anything. He was useless. He deserved to die, wasting his time in this fantasy Norte, his body filled with artificial innards, and with a metal head “generating black hole horizons of hate, and pestled graviton dust.” Whut the fuck. Que carajo. A quien chingados le importa. Xandra shrugged at Ernesto’s snub, then nodded to Hector that they would resume the tour. Ernesto had already dismissed the pair by busying himself with customers. Hector lingered between them in his own private nepantla. He had been expecting more violence from Xandra. Without it he was at a loss. At a loss. An expression in English that cuts with a cool hiss. The sound of Estoy completamente confundido was like blows to a punching bag, but At A Loss, (ssssss) that took out the blade. Take out the blade, vato. A mortar of a vortex Bro. Xandra had gone ahead. He ran after her. 6. Xandra’s Surprise Xandra said, “Here you are.” He caught up with her at another seller’s table. Behind its wares were his cousin Julio, his sister Luna, and his mother, Reyna. Julio laughed, and his sister and mother cried. They all ran to Hector. His mother clutched his neck and wiped away her tears, and his. She said, “Julio brought us. We heard you had come down the mountain.” Hector said, “They put me in jail. They were going to kill me.” “The birds came again. They saved you.” She couldn’t stop crying. Luna said, “Mama, mama, stop it, he’s ok.” Luna held her, then gripped Hector’s shoulders tight and shook him as if to prove to their mother he was really there. No one messed with Luna. Small, hard and fast, she could have easily beaten back Hector’s tormentors. She knew better than to try. In their town the shame of a sister bodyguard would have only made things worse for her brother. They kept their distance from each other. For Hector it was like waters under a frozen river. Family and pride coursed beneath everything. Sometimes a bubble rose up, bounced against the ice like a pearl off its string. Her touch startled, and hurt. Hector peered over at Xandra and imagined them alone together. She stood apart, watching with a cool smile and swatting away a whizzing taqueria drone like a gnat. In the bustle of the market and his family’s excitement he and Xandra shared a quiet space. But no. The distance between them was unbridgeable. Yearning for her attention after she had throttled him was a pitiful masochism, some unwelcome remnant of his battered, needy childhood coming awake like a thawing limb. It hurt so bad he would just as soon saw it off, chew it off, as feel. When would he learn. He turned his back on her. Julio had returned to the table and called for Hector to join him. Among fruits, sugar skulls, a bowl and pestle, a hot plate and glasses of tinted Horchata he saw twenty or more of his Calavera sculptures. They were deployed over a red tablecloth in martial ranks like lead soldiers. Many were the robo models he thought had been destroyed the night he was beaten. “How are they selling?” Hector asked. In answer several shoppers gathered around him, carefully holding and turning the sculptures close to their eyes in studied trance. Hector thought it was a joke. Within seconds Julio had taken their money, wrapped six of the miniatures in tissue paper and boxed them in white cartons, the kind used for Chinese take-out. Julio said, “I tell them you’re the artist, you’ll be mobbed.” “How much are you charging?” “Sixty dollars each…” “Sixty?!” “…but I’ve been thinking of raising the price. We’re running low on stock. We’d better get you back to the shed!” Hector picked up a sculpture. Julio gave it a nod. “A hundred.” It modeled the trio of skeleton cops who cowered beneath the black birds. The base covered Hector’s palm and extended half an inch over his open fingers. Three marble-sized boulders surrounded the scene. The middle one bore the X’s and skeleton doodles he’d carved out of boredom. He remembered his little models as being lighter. Did everything have more density here? His feelings were more felt. His sister touched him. Yet his pain-free feet walked a little off the ground, and fruit and tacos sailed like balloons. He bounced the model in his hand. Julio wouldn’t meet his eyes. Hector said, “The color is different, too.” “They got damaged, cuz. I had to touch them up.” Hector said, “Did you know there’s another figure in this one? It’s me. I’m hiding under this huisache bush here. See? I’ve got a little X on my hat, so the birds could recognize me from the others. It worked, huh?” Julio peered at the model and twitched a nervous grin. “Hey yeh! How ‘bout that? That’ll make it a collector’s item even more!” Luna and Rena huddled behind Hector, chins hooked over his shoulders. They both cooed at the model, then stiffened. Luna said, “What are you doing?” Hector had twisted the skull off one figure and pinched it flat between his fingertips. He did another and rolled the two little skulls into a ball, like a nub of gum. It smelled bitter. Hector turned the sculpture over and pulled the wood backing off the base. The same gummy stuff was pressed into the corners. Julio said, “It’s just to weight it down, cuz.” Luna slipped her arm around Hector’s neck. He rolled his shoulder and shook her off. They were both surprised by the force of the move. She grabbed again. He gripped her hand and squeezed until she was on her knees. Years of handling a machete charged the muscles in his arm and hand with strength he never tapped. Until now. “I’m sorry. I’m sorry.” He let her go but she stayed on the ground and pushed away his outstretched hand. He had a sudden sharp memory from childhood of playing with her on the floor at home. They would move their action figures and cars and horses this way and that way, according to rules they alone seemed to know, and know without speaking. Now she picked herself up, her face averted, and went back to Reyna. Neither of them would look him in the face. In a blur of shame and anger Hector tossed the decapitated figurines on the table, and dropped the gummy stuff at Julio’s feet. Julio picked it off the ground. He blew off the dust. “OK, cuz. It’s Chiva. Black tar heroin.” “It’s not black.” Julio smooched the tar back onto the figures, trying to remold the skulls and police hats with angry pinches. “I step on it with a little white sucrose. I heat it soft to hard. Pound it down and it makes it nice for taking up your nose. One stop shopping. Though folks here prefer preparations at home. They’re very clean.” Pestled into graviton powder Hector said vaguely, “No wonder Nepantlia is all smiles.” He couldn’t take his eyes off the tiny black skull head. It grew large, filling his visual field. The blurry face beheld his. It blinked and smiled out of an adoring vortex. It had a face like Jack Kirby’s Thing from The Fantastic Four, the lovable but truculent, Neanderthal-browed mug of orange alligator-fissured skin. Only this thing was not cute. It was made of shit and disease and worse, it was a kid underneath, a little kid struggling to breath, to scream “Something’s happened to you, cuz. Come down from the mountain and you’re all changed out, man.” Hector rubbed his eyes and shook away the thing crowding his vision. Julio sighed disgustedly and got busy with two more customers. They scooped up three more sculptures each, and even took the one with the blobby heads. They paid with a Mastercard hologram. Hector watched it flutter into Julio’s box like an autumn leaf. He could feel Luna, Reyna and Xandra glaring behind his back. He wanted them to disappear like the Mastercard. Julio thanked the customers and closed the box. The sales had restored his cheer. “I know what you’re thinking cuz, but people here aren’t junkies. Not like the states. Completely different. They get high, or something, but just look around! They’re all strong and big and wear capes and have flying fucking cars!” “And flying money.” As if on cue a pair of the silver vehicles whooshed over their heads. They were so low their magnetic fields tingled Hector’s scalp. In their wake the spectrum curled into a froth of UV. Finding his mom and Luna had only brought more loneliness, painted in these new colors. In this place, time measured something besides time. How could he have made sculptures of the birds killing the police when it had just happened? Yet it seemed there was a memory of building it. He came here straight from the massacre. Had he made the sculptures here, while recuperating from Xandra’s beating? His face flushed and his hands clenched cold. Too many damn beatings. Don’t cry. He cried, and started walking. Behind him he heard Xandra said, “Let him go. He’s not ready yet.” He left the market, with the purple mountain as north star. No one called out, or tried to follow. He was glad, and furious. Time measuring something besides time. Color frothing to UV. A mortar of a vortex. He walked on. No one seemed to notice him. The music and buzz of the market faded and stilled. The streets emptied. The sun dropped and blurred red. His Nepantlia jumpsuit wasn’t made for the sudden chill. He beat his arms and turned the corner. Ahead was a narrow dirt alley between old stone walls. He went in with a rueful sigh. He’d followed his homing instinct for el barrio. El zona. Dirt. Crap. A wooden door at the end of one wall opened, and Ernesto the candle seller emerged. He held a sugar cane machete in each hand. He peered up and down the alley and then waved a machete at Hector to come inside. His face offered no comfort. Hector walked on, then turned and went back. Inside it was dark, but warm. Hector followed Ernesto down a short flight of stone steps. For the first time in Nepantlia the air was not fragrant. It smelled like cinderblock and mildew. Like burned peppers and chorizo on the grill. Like dung and petcoke and wax and stale incense. Like home. Ernesto opened another door and they were in a large cement-walled space under florescent lights. A listing gas stove was stranded near the middle of the room, as if it had slunk part way to the wall and given up. One burner glowed under a coffee percolator that croaked and spit. Around the room were a few scraps of broken furniture, patched with duct tape and odds and ends of shim and splint. Twine-bundled candles, metal molds and blocks of amber and pink paraffin lined sagging shelves. Dried wax splattered the floor like old vomit. Everything was dusty and beat. But on the gray walls were three old movie posters of lurid monsters and naked women in acidic colors and jagged, bloody fonts: SANTO VS LAS MUJERES VAMPIRO! SANTO EN ELA HOTEL MUERTE! LA NAVE DE LOS MONSTROS! Hector was lost in the posters and jumped when Ernesto dropped the machetes on a wobbly table and said, “Got a left and right-handed one there. You can take what suits you.” “I’m not cutting sugar cane.” Ernesto looked at him dully. “Neither am I.” Hector sneezed. “You need to dust this place.” Ernesto cleared a chair of newspapers and slapped it down in front of Hector. “I’ll attend to that right away. Coffee?” “Sure.” Ernesto took a couple of mugs from a cabinet, blowing and wiping them free of dust. He said, “You like the movie posters?” “Santo? Sure. Santo rocks.” He sat down and said, “You going to show me how the true flames burn?” Ernesto stopped pouring. “What?” “It’s what Xandra said in the market. You’d show me how the true flames burn.” Ernesto said, “Milk? Sugar?” “Black.” Ernesto handed him the cup and sat down on a stone plinth to blow on his own. Hector said, “I didn’t mean to hurt them. My sister and my mom.” Ernesto stared into his cup. “Xandra said I’m not ready yet. What did she mean? Not ready for the true flame?” Ernesto snapped, “There isn’t any true flame! Not in this place.” “Then what..?” “Xandra is full of shit, and not fully human. I’m not sure about what seemed to be your mom and sister. This is kind of your hologram, Hector. You’re the only one who can know for sure. But if you ask me, Xandra thinks you’re not ready to come back, to have the shit beat out of you again, which is what they’re waiting for. To get you taken apart, and put back together. Again. And again. Until you can go back out, and sell. And use.” “What the hell are you talking about?” Ernesto rolled his eyes. “Ay dios. How many times do we have to do this? I guess I should be happy you’ve made it this far. You could have just walked on, lost in the cloud city. Sooner or later you try for the border, but the robots stop you, or Xandra catches you and beats you, and it’s back to the travelrama show with Xandra and the market. Julio recruits you, you go north to sell chiva, come back home the big hero, lots of money, gifts for mom and uncle Armando, jeans for Julio, only you make the big mistake and sample your own merchandise…” “I never sold that shit! I never used it, either! I’m an artist!” “Think back.” Hector had a headache. His aching eyes were pulled back to the monsters in the posters. Silly cheap rubber Cyclops heads, vampires, ghoulies, wolfmen and blue demons, all snarling and drooling down at beefy El Santo, his flawless abs and pecs glistening under luz mala lights. And in their midst the black, gnarled mess of a head with the kid’s eyes, swelling up and sniggering right at Hector. Back home he could understand a blind eye to the black tar. Most people in his town weren’t for it, but the money talked sweet. Even his mom and Luna just went quiet when the neighbors talked about one more young man leaving to work north, following their older brothers, cousins, uncles or neighbors already set up in business. And after a few months they came back with new jeans for everybody, stuffed with cash – much, much more than you could make cutting sugarcane, and not hard on your back or your arms. They brought back money to replace leaky roofs or buy new refrigerators or even build a new house, get a new truck. The town sprouted dishes and rebar, and new boomboxes thrashed the air awake, like pounding the dust out of stinky old carpets full of piss and scorpions. And they did it without guns or bad business. All you had to do up north was drive around with some little balloons of black tar. Just tie them up and stuff four or five in your mouth. The boss gave you the car, an apartment, food. You just sold your load and went back to your apartment. You counted the money and wrapped it in rubber bands. Put it in a shoe box. Filled new balloons with little bits of tar. Then you’d get a message on your phone. They gave you a phone, just for that. The message had an address. You’d stuff your mouth with the balloons, you’d go out and do it again. The customers were ok people, and some of them were really nice. It was all simple. And if the police stopped you, you just swallowed the little balloons and shit them out the next day. Hector had imagined the taste of rubber, the slithering swallow. Gulp gulp gulp gulp. Then passing them with a grimace. Putting the chiva in clean new balloons. Setting out again. Hector had heard the stories so many times it was like he’d been there. Nobody knew Hector could speak and read English. If they did, he would have been hounded mercilessly to go north and sell tar. He could even start up his own business, they would say, hire your own drivers and develop your own clientele. Then you’d be free to make your sculptures, not just miniature ones but big shit, made out of real materials meant to last, and to stand proud in galleries and museums. And Hector had thought, (hadn’t he?), that maybe he should. Maybe he would. He could get his own money. Help his family for once. Get away. He imagined it all until he remembered it. Yes. Hector went north, and got hooked. First on the money, then on the product. He started using, and selling more to use. And using more to sell. He heard his own voice from far away. “So that’s why I ended up here, in Nepantlia?” “This isn’t Nepantlia, Hector. It’s America.” “I want to go home.” “You can’t. Not yet. There’s only one place you can go. Nepantlia. The real one.” “When?” “First, you’re going to have to lose all the shit that they put in your body to keep you going. And it’s going to hurt real bad.” “I don’t care.” “And then we’re going to have to fight our way out of here.” He went to the table and picked up the machetes. “Are you a lefty, or a righty?”

0 Comments

|

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed