|

bart plantenga is the author of novels Beer Mystic, Radio Activity Kills, & Ocean GroOve, short story collection Wiggling Wishbone & novella Spermatagonia: The Isle of Man and wander memoirs: Paris Scratch and NY Sin Phoney in Face Flat Minor. His books YODEL-AY-EE-OOOO: The Secret History of Yodeling Around the World and Yodel in HiFi plus the CD Rough Guide to Yodel have created the misunderstanding that he is one of the world’s foremost yodel experts. He’s also a DJ & has produced Wreck This Mess in NYC, Paris & Amsterdam since forever. He lives in Amsterdam. A Black, A Catholic, A Jew, A Hedonist, A Protestant & An Atheist He was going to live forever, or die in the attempt • Joseph Heller, Catch-22 The Canary-yellow, souped-up Beetle’s engine is straining, screaming in an octave somewhere between a Hendrix guitar solo and the collective anguished cry of an entire generation ...

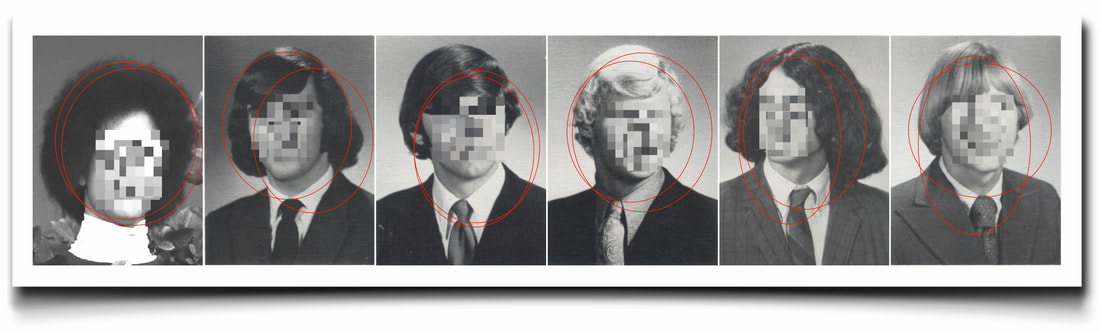

What I can’t get out of my head is the image of Jimmy Gilmore in the dark, flickering-low-wattage-bare-bulb basement of his Utica home, dangling from the end of a rope, not a rope, a kind of silk sash. It is called a fascia, it seems, and it was probably black and is usually worn by Catholics around the midsection, above the waist. These details you don’t want to investigate, but you do anyway. Because you think, maybe wrongly, that details are the key to unlocking the mystery – of somebody you thought you knew but didn’t at all. Am I the only one thinking this? I did not know he was raised a Catholic, that his parents were rich – compared to us, at least – that he despised his parents [but not really] and what they stood for but outed it in a muted, respectful manner. What did we know: He righteously refused to ever be influenced by this upbringing, wearing hand-me-down clothes and the cheapest sneakers, didn’t even own a winter coat, a comb, failed to shave and didn’t even own a stereo or get his hair cut at the chic Hair-Em in Langdon Plaza in Elmira. Jimmy was fearless and wanted everyone to know this or at least that there was nothing to fear but what fear does to our souls. Or something like that. It could very well have been that he just wanted to take the piss out of us on our long talk-walks, our scruffy-denim version of Aristotle’s Peripatetics as we slowly drifted across the dark fields between the high school and the village swimming pool in the languourous summer evenings after dinner. Along the way he’d leap up on the hand railing on the bridge that crossed the highway and without even focusing, he’d walk across, balanced wackadoodle-daredevil-style on the railing – embarrassment if he fell our way and certain death if he fell onto the highway. And any consolation for being right would be trumped by the fact we’d be panicking, puking, and swearing to the highest heaven ever imagined. Fact: He never fell, which was his Aristotelian teasing out the “why” of this ridiculous thing called fear, convincing and impressive and yet, in the end, his accumulation of facts still led to one universal truth – by the next bridge crossing we were just as shared scitless, schizofrantic, yelling, pleading with him on bended knees to PLEASE come down, be normal, reasonable and spare us the horror of the impending splatter. His signature moment: he’d feign losing his balance, arms flailing, legs wobbling, a mocking-quavering WOEHOE, as he for a moment held our collective breaths in his midst, teasing out the terror, taking mental snapshots of our fear-contorted faces for posterity. No doubt: We shit bricks then, continued to shit bricks for years, got better at disguising our quivering brick shitting and in college acquired articulate rationalization, justified paranoia, vainglorious suspicion that would place us at the center of the universe’s intrigues as if we had by merely dreaming in dark fields in the middle of nowhere changed the course of human events. However, the weird thing is: You know somebody eight, 10 years, when you suddenly realize you don’t know anything about someone except a list of movies, bands and books he has mentioned and some outrageous acts, that he despised school but got mostly “A”s, scorned organized sports, never practiced and was still a top athlete. And we, the six of us, were best friends – whatever that means – and so, how does it happen that it does not happen, this knowing much of anything about each other? One minute me – I’m Bertrand Planarien – and Jimmy and Stuart and Marcus and Jasper and Peter are plotting a big adventure, the next we are heading east on 17 – we’re 17 heading down Route 17! – clear as the clear sky yesterday, topping the speed limit, like there’s no tomorrow, no calendar, no agenda, no plans, no future. Probably won’t be, if news out of Vietnam was even half right – “Napalm Accident Kills Vietnamese Civilians.” Our goal: Last Tango in Paris was playing in only one theatre within a 300-mile radius of home – in Binghamton. What are we doing telling our parents about napalm and “friendly fire” anyway? What business do we have knowing what “friendly fire” even is? And insisting it means more than what it means? It’s a metaphor, mom. We were standing on the brink of being drafted into a military we despised, to fight a war we didn’t believe in. Guidance counselors all acted very concerned, did damage control, pushing the patriotism-plus-reasonable angle to persuade us to join – put in 20 years means a pension for the rest of your life. Most guys our age didn’t begin researching until they received the letter ordering them to report for induction. Others thought it was smart to sign up right after high school as part of the “Buddy System.” The tag line: “Who better to watch your back than your buddy?” We prepped a year early, watched the draft lottery on TV, August 1971 – silently gazing, glued to the set as U.S. Selective Service members wandered around a dour stage. On a no-nonsense fold-out table, a giant glass jar held 365 blue plastic capsules containing dated slips of paper rolled up inside. Some big Republican, grey guy strolled out, introduced the event. He reached into the jar, hand rustling the capsules, and pulled out the first capsule. We studied the process and, yes, after the fifth number we got the drift, it had sunk in – we were screwed; at least some of us would be. Peter – from a large Jewish family, in a house where books lay splayed open, spine up, everywhere – turned down the sound and cranked up “Fortunate Son” on a cheap hi-fi unit so we could all sing along while the lottery mimed along its ceremonial path of misery, and we sang louder and LOUDER than any military choir ever: “It ain’t me, it ain’t me; I ain’t no fortunate one ...” Me and Stuart, the Protestant who listened to songs of torment, had “permanently borrowed” a map of New York State from the school library – laughter. We laid it out and – follow his forefinger – plotted our escape route to Canada: hitchhike to the Canadian border, get off the main road, find dirt roads, two ruts, fields, woods, cross the border through the trees on foot with a knapsack of apples, matches, cans of soup, Swiss Army Knife. In between somebody’d yell some anxious obscenity at the screen and we sang: “it’s one, two, three, / What’re we fighting for? / Don’t ask me, I don’t give a damn, / Next stop is Vietnam.” We stared at the map, thinking that if we stared long enough, each of us would find his own escape route. Stuart declared that first we’d borrow his parents’ Chevy Nova, do a test run. “Whose up for it?” “Take me with you, man,” Marcus said, his afro, you couldn’t help but notice, had the awesome breadth and volume of a universe according to Sly Stone. “We’ll say we’re going to Watkins Glen, goin’ campin’, the final hurrah before college, go skinny-dipping up top of the Glen. Too treacherous for the Glen’s fat pigs to trek out there and bust us. Next day we head to Ithaca, Utica ...” And we – me and Stuart – did just that, singing along to the radio out of Ithaca: “Some folks inherit star spangled eyes, / Ooh, they send you down to war ... It ain’t me ...” We drove to just south of the Canadian border to check out Mooers, NY, population 400: it was the smallest, most inconsequential, obscure and unlikely border town ever put on this earth for the likes of us. We parked the Nova at the Mooers Gas Mart, shopped there, found a few worthwhile useful survival basics: apples and potato chips. We hiked out Bush Road, crossed a creek with no name and up Blackman Corners Road a ways before we tumbled down the bank to the creek and followed that clandestine trickle for about three miles until, consulting the map, matching the creek’s twist and turns, we figured we must have been in Canada – no fences, no checkpoint, no flags, no fanfare. Perfect. See you next year, same place, same time – a week before we were to be chauffeured to college by our teary-eyed parents in station wagons, a chair tied to the roof, lots of advice, turtleneck, records, paperbacks, and shopping bags full of school supplies as a gift from them. Instead, we’d leave notes behind saying we were going to be OK, mentioned Montreal, and as difficult as it was, signed our notes “love”. “We’re gonna hitch up there and then head to Montreal.” “Why Montreal?” “Friendlier toward draft dodgers.” We’d seen some foreign films, a couple by Godard, and were sure the French and people of Montreal were friendlier and more anti-war than, say, people in Toronto. We’d seek sanctuary with Roxanne who lived and worked in a hippie store there, and volunteered for a draft-dodger counselling organization, the modern equivalent of the underground railroad, run by “Quaker radicals,” who helped draft dodgers get settled. “I’m going skiing,” Jasper declared, with a casual flip of his long blond curls, “off the grid, no forwarding address, AWOL.” Jasper, the “Hedonist,” the guy with the car, his yellow Beetle – it was HIS – had this knack of yanking everybody into a good time, could crash a party and by the end, the hosts are thanking him for crashing their party. He could make becoming a ski instructor seem like a revolutionary act, a blow against seriousness. “Where?” “Colorado. There’s a movement.” “Ski to be free?” “Your funny Marcus.” “I can survive on ski lessons, drink Coor’s by the campfire.” Jasper: football-track star, ski-guy, Downhill Racer, from a neighborhood of large homes, expansive, manicured lawns that need upkeep by short men from south of some border. He knew he was one of those “it” people, nominated for prom king and stuff. But, at least he had the good sense to laugh it off. He probably also knew that a closet full of trophies couldn’t be melted down to a single nickel. “Sounds good.” Marcus, however, thought he might enlist instead, betting that with his brains he could land himself a noncombatant job, shuffle papers. “And then I’ll rob the government till with the GI Bill, go to the college of my choice and get my thrill.” “... Meet a coed named Jill.” Peter thought he’d either go to Sweden or manage a 2-S college deferment. After all, his father was anti-war AND a guidance counselor. “... Whose on the birth control pill,” my final word. “A- in poetry. Trophy on the window sill.” Jimmy, being ever the buffoon to highlight the absurdity of life, stood up, aimed his imaginary M-16 and declared: “I wanna kill me as many gooks as it takes to become a general. They say 500’ll do.” His outrageous proclamations were accompanied by his shambling manner, a nonchalant, aw-shucks-ing of his anti-establishmentarianism whenever he saw fit, which seemed to be a consequence of his avid reading and rereading of Huckleberry Finn. “I’m gonna let myself be drafted and then do the insane thing, stick a Hershey bar up my ass crack and then during the mental status interview wipe my butt and eat it in front of shrinks as advised by the Yippies to get a 4F, unfit to serve in the Armed Forces.” “You could just be a homosexual deviant. That usually sets them off.” Actually he had already decided to become a Conscientious Objector. And me, the atheist alien with a Green Card? I was going for draft dodger. The idea of killing any person – even Hitler or Nixon or Westmoreland – was a bridge too far toward inhumanity or wherever. OK, I was a naive alien with no roots, no hometown, no grandparents, no family tree, who thought poetry could save the world. So shoot me. “You got the choice to save thousands by killing Hitler and you’d refuse to kill him?” Jimmy wanted to start one of his long philosophical debates. “I’d shoot him in the leg, put him down, capture him and then force him to watch documentaries of all the suffering he caused every day for the rest of his days.” I sort of knew it would never come to this. “Maybe pillory him and Himmler and Goebbels and let Jews and others throw pig shit and rotten fruit and maybe even some stones. I’m into it – even as a pacifist.” Peter had mulled over the options. “I’d let Jews come by to spit in his face and tell him their stories of woe.” Yes, my status as draft dodger would embarrass and confuse my parents; I’d get called coward, alien traitor, be snubbed, denied jobs [that I didn’t want anyway] but ultimately I’d find some things that would give my conscience a rest: read Vonnegut, Twain, Heller, Orwell, Marx, Whitman, Abbie Hoffman, Leroi Jones and Angela Davis, listen to spiritual jazz to not feel totally alien. Other options we’d heard about: Do prison time for refusing to serve and hope for early parole, get a teaching degree deferment, claim fake medical problems like poor eyesight or flat feet, shoot yourself in the foot, fake mental illness by using psychotropic drugs, fake a stutter, wear women’s lingerie and make-up, get convicted of a felony, become a CO based on religious or ethical beliefs and accept alternative service – work for VISTA, build public housing in Philadelphia. “I’d work in a mental hospital or join the National Guard,” Jasper felt best when he acted like he had it figured out. “But I prefer ski instructor – maybe to disadvantaged kids in Denver.” “And then what? Be ordered to shoot students on campus – ‘four dead in O-Hi-O’?” Peter. “Yep, go weekend warrior, maybe get to shoot dirty hippie students at a demo. Keep America safe from its young,” Jasper. You had to laugh. No. You did. We were all pretty smart, although not as smart as we thought we were. It was pretty clear: society wanted us to believe that it was perfectly normal and polite and patriotic and manly to fight in a war that could not be made sense of. That was last year, now is a year later and the next draft will be televised and we will watch it as a group one last time before we are dispersed to our individual fates, darting into whatever abyss, uncharted territory, ripped apart, as we get chauffeured, each to our chosen campus. This was the big drawing and we were eerily fixed, gnawing fingernails; Marcus couldn’t even be in the same room as the TV. The call up cut-off was 95, I think. My number, birthdate July 16 was 74; there it was pinned to a bulletin board grid so, definitely going – if they had their way. I saw myself following the mental map I had memorized to the Canadian border. Peter drew 56, Stuart 93, Marcus 222, Jasper 289, Jimmy 351. Our gazes gave it all away – none of us were who we were an hour earlier. Less blood in the face, a little less alive. The beers purchased as solace went unopened. “No fucking way will I ever, EVER buy a Norelco Triple-Header! No to Norelco!” Marcus’s reaction to the Norelco commercial during the broadcast was loud and clear. I tried following up with Stuart. No answer. The prick. Revealing his chickenality. Anyway, we soon got off the hook because the draft numbers were never used after December 7. Where were we?: The 4-cylinder engine is straining, screaming in an octave somewhere between a Hendrix guitar solo and the collective cry of anguish of an entire generation. Jasper, his face, pressed up toward the windshield, driving with his chin balanced on the steering wheel. We, with five faces out the window, warm wind whipping our glorious long hair – every inch another blow against the empire – screaming back, imitating the whine of an engine too long in second gear to the tune that describes the terror and joy of impending graduation. And for those few seconds, those few hours that day, we were free birds floating on the breeze of now, being none other than ourselves, unburdened from the history of a people consumed by suffering and responsibility. And freedom felt good coursing through our veins, forever free to pursue our own trajectories of increasing self-doubt. We raced eastward like there was no tomorrow, no speed limit – 65! 70! 75! – thrust into the next beyond, overcoming gravity and any burdensome G-forces. Maybe there wasn’t much to look forward to except us giddily waving obscene gestures at the cars we passed and suddenly ... a discernible silent distance between thoughts in Jasper’s Beetle, as if each thought or utterance was buffered by contemplation, like thought clouds serving as safety airbags between head and hard reality. But then the resistance burst out in earnest. We we were no longer ourselves and that suited us just fine: “War, huh, yeah / What is it good for? / Absolutely nothing, “ Marcus sang it 10 times but it didn’t matter because he could sing like a mofo. “ War don’t make boys men, it makes men dead.” Jimmy swore he came up with that himself. “Fuck War, I’d Rather Be Skiing,” guess who. “Bombing for peace is like fucking for virginity!” Everybody liked that one and so I followed with one of my own: “Sex Porn better than War Torn.” “WAR IS OVER IF YOU WANT IT!” Stuart was trying to get the hang of it. “Fuck the man. Fuck school. Fuck the FUCKERS!” Nobody and I mean NObody had ever seen Peter lose his cool like this. And then we aburptly and collectively shifted gears, into 5th or 6th or something, entering a magical realm of lubricated harmony – you feel invincible, like the superhero you imagined you were at 11 but now with a James Bond coven of babes. Living in the moment is a cliché, but if you embrace it with unselfconscious earnestness you can surf perfectly on the wave just under the curl, something you will never ever be able to replicate again. We looked out the Beetle windows and everything looked suddenly totally essential, colorful, meaningful, impossibly important, full of portent, literary allusion and synchronicity – on fast forward. Jasper likes to make the engine scream and beg before shifting it into third and, if she’s real nice, into fourth. He plays it like a lead guitarist plays his Gibson. We don’t for a minute think it is insane to be screaming in unison along to the scream of a 4-cylinder engine pushed to its limit. Because that is why there are limits. To push. We can all name guitarists other than Hendrix that capture this sound. If I start the list we will soon all be chiming in. These guitarists play that sound at us and we are understood, represented, on a map. When their guitars explode in balls of flame, we know we are immortalized. I won’t name any of them here. Because this is not about music appreciation. We are whooping it up, high as Droogies, because we are on an adventure, you know, thrills to get us out of ourselves. The more distance between thrills in our upstate dead zone, they say, the faster you got to go to get to the next thrill. You don’t reach it in time you pass out and away. It’s not sci-fi, it’s the only thing we got except stories about life in New York City – that girls in Greenwich Village are so cool, they proposition you and offer you thrill drugs [LSD] that will throw you permanently out of yourself. Like being thrown out of your own house – forever. We sing: “I’m a boy and I’m a man” in unison, screaming forehead to forehead: “I’m eighteen / And I don’t know what I want.” Going hoarse in the knowledge that even as loud as the top of your voice will never make it clear to them – or yourself – why we are here doing what we are doing. Jimmy will laugh that laugh – a chuckle like someone jingling a pocket of loose change – like he knows, like the laugh is a secret password into a secret society of people who wear a fez, like he’s been to the basement and found the books of Kafka and Nietzsche, like he’s lived nihilism, can define existentialism, is always saying things like: You didn’t know that?!” Jimmy and Peter were masters of all isms and were sure that most isms were bad. Stuart believed in certain isms: transcendentalism, Buddhism, altruism, holier-than-thou-ism. I believed in animal magnetism, the magic of a beautiful face to distract and change fate forever and ever. We park downtown and the STRAND Theatre marquee is worth a picture: LAST TANGO IN PARIS STARRING MARLON BRANDO 1:15 4:25 7:30. The Strand had been in the news: cops had shut it during the premier of Deep Throat some months back. It had only reopened a month ago and was now playing another controversial film. We support people who go out on a limb for the naked arts by attending the early show. We were lucky; the ticket seller in the booth was a young girl and Jasper and Marcus were good at schmoozing, flirting, flattering her about her great feathery fake eyelashes, as she chewed pink gum, unsure of what to make of us. “Don’t worry boys, I’m not gonna turn away mature foreign movie lovers like yous from seeing a film just because yous ‘forgot’ your IDs.” She handed us our tickets, smirked with that O-yea-I’m-wise look, adding: “Keep it in your pants, guys.” We broke out into six urine-warm grins and flipped her our best solidarity fists. She didn’t care and was already back to reading a magazine as we walked off with our tickets in hand like we were pilgrimaging to the Holy Land, lightweight Bible under armpit. As a nerd, trying to be super cool requires a basic debriefing, learning to go totally disaffected, drained of all traces of enthusiasm, glee or wide-eyed, saliva-producing horniness and acquiring that dapper Buddhist-meets-James-Bond inclination that consists of a veil of composure-under-duress-who-gives-a-shit cool – we studied Steve McQueen, Paul Newman, and Jean-Paul Belmondo movies in that regard. But the learning curve is steep and the stakes are high. We’re here for the early show and there are maybe two dozen other stragglers, already slouched way down so all you see is their cowlicks. There are maybe two women in the whole theatre. Debriefing: don’t do the math – about 8.5%. They were probably liberal arts professors at SUNY. You know the kind: make crow’s feet sexy and with casual scarfs of bright strips of fabric knotted on top of the head and looping behind the ears, long enough to drape back over the shoulder, which expresses verve and just the right amount of disdain for the rest of society. We are sitting next to each other and like when you visit the urinals, the unspoken rule is during a dirty movie [even if it is art] you do not look but straight ahead – especially during the butter scene [we’d heard about]. I tried my best to, from the corner of my eyes, observe the rest of them with their eyes pegged to the screen, with nary a comment, a few swallowed guffaws of Jimmy’s – especially during the bathtub scene. We emerged from the theatre wondering about the film. Hands in pockets, a quiet that you can hear; the gears are turning and none of us want to admit we had a boner. The moviegoers, us included, seemed almost shell-shocked or hoodwinked or annoyed that we were confused; the lobby smelled almost like fear. “10 boners.” Jasper. “But don’t ask me to explain it.” “10 piles of crap.” This was the breadth of our ratings. Stuart thought that the horniness quotient, or any romantic beauty, was “spoiled” by death and suffering and cynicism. “Maybe, in a way, we’re being shown there will be no pat happy endings for the rest of our lives.” While Peter could write reviews, term papers on subjects like this, I ended up tracing Maria Schneider’s near-perfect breasts with a #2 pencil and tracing paper. Jimmy thought that Brando’s insistence on a return to a time before we had names refreshing – Buddhistic almost. The pursuit of anonymous, aggressive sex, we gathered, was a way to obliterate the past, although, I was mesmerized into admiring cluelessness, you know, where the brain goes goopy, and form trumps substance, beauty trumps meaning. “It’s driven by Brando’s grief over losing his wife to suicide.” Peter was searching for motive because you never know if we’ll some day be confronted by something similar: “In talking to his dead wife we see a man caught between existentialism and absurdism.” I was only half following. Vivid images of her face, hair, breasts, belly filled my brain to overflowing. “It must be the most powerful erotic movie ever made,” I dared to say. “Well, how many have you seen. 101 Dalmatians is not porn.” “It lacked tenderness, intimacy, human kindness.” Stuart hated that the movie refused to conform to what he thought sex was – love embodied. He wanted the movie to lift him out of himself and offer hope, the hope against all hope. He also condemned me for having fantasies aroused by the film, calling it a sign of weakness of someone who has never had a “real girl friend”. At times, you wanted to just slap Stuart up. That is how pained he was by the mere existence of pain, of slights, inequities, things that did not make sense. Marcus and Peter knew what it was: a self-serious lack of any appreciation for humor. Blame it on Calvinism, on his parents who were uptight – not awful – just reserved, so that evocations of passion were relegated to stiff handshakes, unless a half-smile between spoons of lukewarm soup was supposed to light a fire. You know the kind of smile used as churchly propaganda, like an open door, like “Welcome, aren’t we Protestants welcoming?!” Let me tell you what Stuart hated the most: becoming his parents. And, as if there was some magnetic genetic pull in his case, he became over time increasingly puritanical, judgemental. “You’re either judgemental or mental,” Peter used to say in response to some intolerant Stuart blurt. But, since I’m writing this, I’m convinced that we all sensed somehow that Last Tango was profound and that, despite feigning coolness – or revulsion – it overwhelmed us in a way that only great art can. “Stuart, you’re so frickin’ transparent. You hate it because you weren’t in it. You so wanted so bad to be in that movie.” In the cartoon version, I would beat him in, sneak in through the first panel to replace Brando before shooting starts. I was immediately smitten by Maria Schneider. Period. Not because I was grateful to her that she was so naked. No, not out of some horny perversion. No. More because she embodied a kind of being hovering between innnocence and experience that I imagined I could communicate with. Six months later, on campus, I bought the Playboy issue featuring her. I remember what a big deal it was: I invented excuses, scenarios, studied the cover, would say I liked reading the “Jazz and Pop Poll,” or I’d been assigned to read the John Clellon Holmes piece on Kerouac for poetry class. But the vendor, with the wrinkled face and a cigarette butt emerging from it could not care less because morality was just a stumbling block to sales and sales equals survival. I clipped the photo of her squatting naked, nude in wet sand near the sea. Folded it so that it appeared face out in my wallet, looking like a real photo that maybe she had sent me, which – I never told anybody ever – served as a template for the ideal woman, body, hair, elegant innocence, voice – that French accent. [Her actual tragic life would not concern me for another 30 years, when I learned how she came unraveled and I was not there to hug her or whisper dulcet encouragement into her ear.] And a year-and-a-half later – placing the photo of Schneider next to the few photos I have of Laura from back then – I realized without ever consciously using that template to hunt for a body-face double I was, indeed, dating a Midwestern version of Maria Schneider. How weird is that? Enough to have kept it quiet for all these years. We are now singing so loud that you might think we are leaping across that great distance between who we hope to be and what we fear we will become. “‘The Brain – is wider than the Sky.’” Stuart could get cryptic for a multitude of reasons. I’m unfamiliar with these lyrics. And only later learn he’d memorized an entire Emily Dickinson poem he thought appropriate to blurt out here. “The Brain is deeper than the sea ...” “And you and me are free to be you and me ...” Peter had a pointy sense of humor that jabbed at Stuart until it shut him up in a pout. “How do you solve a problem like Maria?” Did Jimmy know where my mind was stuck. “By chokin’ the chicken?” Marcus. Jimmy always seemed to have everything figured out: society was a sham, had to be worked, negotiated... How socks were bad for your feet; how shoes were bad for your feet. How he was going to go a year without wearing shoes – even in winter. Which was annoying because lots of places like malls, pizzerias, and movie theatres had those signs: NO SHIRT NO SHOES NO SERVICE NO SHIT. Marcus had a solution for Shoeless Jimmy. Marcus was a bit of an artist with an eye for rendering. He’d paint a pair of shoes on his bare feet. Nobody would notice. And nobody did. That is the magic of Trompe-l’oeil, of course. Or if people did, they sensed we were too scary-weird to bring it up. Thirty-some years later I get a call out of the blue. I don’t even recognize his voice. It is Stuart, by now a school teacher, speaking like one in complete sentences, becoming the very thing he despised back then. When a high school friend calls you out of the blue after not so much as a word for so long, you know it is not good news like he won the lottery and wants to share it with us. “I have to be the bearer of bad news,” when it’s bad news, friends suddenly go formal, using stiff sentences to hide behind. “Jimmy passed away last Tuesday after a period of declining health.” Everything he said that tried to deny it had been suicide pointed exactly to that very conclusion. I think we’ve all been in a conversation like this: the more some fact is denied, the more it becomes irrefutable, undeniable evidence of certitude. I guess that is why I knew right away it was suicide. I knew from experience, having already experienced the death by suicide of an inordinate number of friends and acquaintances: death by jumping [“falling’”] from a low bridge into a shallow canal; death by automobile [“accident”]; death by “accidental” overdose; death by unhealthy, nihilistic lifestyle [“wasn’t taking the best care of her health” – in other words, wanted to die]. Jimmy had withdrawn from the very life he seemed to always own the better part of, as if life was incapable of putting one over on him, as if life was his for the taking – and ultimately, ironically, had taken him. There was a silence on both ends, the kind where you imagine you are hearing ghosts whispering through your landline. “Well, ain’t that something, it takes a death to bring us together.” Remembering someone you hadn’t really thought about for many years sucks. Why is that? Because you immediately feel guilty that you haven’t thought about them for all this time until it is too late and he cannot really use any of your sudden fond memories ever again. “I feel bad. I blame myself. I saw him a year ago and didn’t notice anything. Nothing. He’s now forever in my thoughts.” Stuart. “I’m sure he’s super pleased about that. It’s like a million dollars in the pocket of a dead man about to be deep sixed.” Me. “I ignored him when he was crying out – without crying out – typical Jimmy. He seemed fine, calm, focused on his stocks, had come to denounce almost everything as godless. “No more Huck Finn humanism? He used to take the piss out of everything crooked and hypocritical. Ranting against every ism – saying we were all ‘ismed’?” “Yea. The laugh was still there but it wasn’t funny what he was laughing at.” There, in my mind, Jimmy is lying on a cold slab with slight bruising of the neck [lighter bruising when a noose is made of a soft material like a silk scarf or fascia] in a morgue, in a somber Utica struggling to overcome its depressing image by “growing its civic pride.” As the metalcore band In This Moment sings in “Utica is a Depressing Parking Lot”: “This beautiful tragedy crashing into me / No foreseeable happy horizon I can see, / Suck it all up with your Dyson, you and me. / Uticans are a depressing lot, hope is bankrupt but its all we got / Beautiful melodies wash away the lies and rot...” To show respect for the feelings of the family and the Catholic Church, The Chronicle-News obit was respectfully deferential, reworking the hanging-from-a-pipe details into an official cause of death: “declining health.” Maybe it wasn’t even Jimmy Gee, the ex-person now referred to as James Francis Felix Ives Sebastian Gilmore. What I knew: born a Catholic, disavowed his faith as a teen. What I didn’t know: rejoined the Church, became an oblate after he quit practicing law. “I just miss him. Have for a while. I miss his questioning of everything – even those who question everything – a contrarian of the first order. But where does it end?” Stuart was in a dour mood, the kind that wafts into nostalgia, that kind of what-if nostalgia that seeks to punish us with regret. “There is no end because inside each lie is a smaller deceit and inside that is subatomic evasion and inside that is ...” Me in a moment of philosophical clarity that startled me. “Yea, yea, remember him up on that railing balanced on one leg over the highway?” “Super smart, but somehow he managed to hoodwink himself, come unraveled, ending up the very thing he despised – a Catholic.” “He became super devout, but still, it was Jimmy. You know what I mean?” “Yea, from an open window with the light shining in, to a door deadbolted shut. I think he ended up Catholic the same way guys end up in a pub – loneliness. No wife, no partner, no cat, no dog ...” “No way.” “Grit thinks he was gay and Catholic – and tormented by it.” “NO WAY WAS HE GAY.” “Did we ever hear him talk about a girlfriend, kissing a woman, sex? He just wasn’t the lovey-dovey kind – ask Grit. Maybe he was secretly gay – and just lost his way.” “HE WAS NOT GAY! And it wasn’t suicide! That’s all sensationalist crap.” “Oh really? So, hanging from a heat pipe in your basement is an accident? Come on. Granted, it could’ve been self-asphyxiation, like some auto-erotic thing.” “He was a good friend, smart, compassionate, but burdened by his inability to overcome his self-perceived shortcomings.” Peter hadn’t said anything until now. “Remember how he used to come over and talk until we all fell asleep. I’d wake up and he’d be gone.” “He was our own Jimmy Reb, our own Dean Moriarity – invinsible – or so we thought,” Stuart was rhapsodizing as we are prone to do when the object is no longer there to hear our compliments. “A dichotomy in many ways – extremely generous to those around him, extremely hard on himself. He used to defend the weaker among us, those who were alwyays getting picked on by others and he’d take the wrath to shield them – truly fearless in the face of danger. But, maybe ironically, he couldn’t accept his own frailties, and get help from others and that made it difficult for him.” We should listen to Peter. “Maybe the god thing wasn’t as spirit-enriching as he thought. Maybe this is where he exposed his frailties to god. Maybe he discovered that god wasn’t listening.” “Like I said, he became very orthodox, really judgemental. His daily routine was OCD but he made it into some religious ritual. Like god even cares that you put your toothbrush in the exact same spot every night. And then his health failed.” Stuart. “What does that even mean?” Peter had no patience for polite clichés. “Maybe he was gay but probably not. I’m positive though that he was scarred by his parents, like all his brothers and sisters. His oldest bro left for Rome and never returned. His sister joined a cult in Idaho and later said their father had sexually abused her. His younger brother fell for the bottle. Jimmy left home before the end of high school and never returned for more than a cordial visit. The father was a bit of a thinker and drinker and drink fueled his violent temper. His mom has been in AA since our high school years. “He warned me I was going to hell for dropping acid 30 years ago. As if I didn’t already pay the price – am still paying the price! I still only have one foot on the ground.” Stuart. “Maybe he put all his faith in one basket and that basket had a hole in it.” The ride home from Binghamton that day: think of a ride from a cemetery after you’ve buried your entire family, with Jasper eerily crusing under the speed limit. Solemn reflections in the side window. As we turned off route 17 to head up South Main, Marcus made us all swear on a stack of The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers comics, Vonnegut paperbacks, Playboys or whatever, that we would remain friends forever. Like a really long time. That was the last time the six of us saw each other together in one place. The big shock: if you ever see any of your old gang again, you remember thinking they had it all figured out back then and you were clueless. They seemed to be able to explain things like they were wrapping Christmas presents, had clever comebacks, hurled brickbats, were late for school, refused to wear socks and, magically, never seemed to experience any repercussions for their anti-establishment behavior, floated along on interpretations of the philosophy they read aloud and there you were, all dazzled and humbled. But then Peter contacted me about John’s death and he said something startling: “I’ve always had a distracted approach to life. I can survive in the world but I missed lots of ops to develop skills, relationships, and talents – I know they’re hiding in here somewhere!” “You sure snowed me all those years.” “You and me. I’m amazed I’m even left standing. I never had any concept of how life should be. So much iindecision and stupid-ass decisions. But, call it accident or divine intervention or guiding hand – yeah, sure – here I still am like a paramecium blindly tasting and feeling its way through life.” I didn’t – maybe you didn’t either – realize until it was too late that they may have been each thinking exactly the same as me, thus creating an odd equilibrium of universal doubt, a détente of mutual uncertainty. But maybe this very “too lateness” now provides an opportunity to reflect – or regret. In any case, the fact that we actually live in a permanent rewind-play-rewind mode and that understanding after the fact – “too late” – makes of all understanding a hollow victory. That’s not much of an ending, but it’s all I’ve got. Unless I tell you what I learned of what became of us: • Jimmy Gilmore’s story we pretty much know. He died when we all thought he would live, if not forever, at least longer than any of us. • Marcus Cleare, after some heartbreak – his girlfriend was murdered in a freak robbery gone bad [which he never discussed, not wanting to play into ghetto blackman clichés] – and after college [MBA], became a stock clerk, and, while playing handball with a neighbor, was offered a position as a property tax appraiser. Unsatisfied, he went on a tear, doing 100 down Church with a hand gun and a Baggie powdered with cocaine residue, arrested, charged and he eventually had to leave the field, move in with relatives in Detroit with the ambition of pursuing something with music. Managed two tribute bands: the Not The Kinky Rolling Beach Beatles [50-70s hits] and Myron Fadin’ [80s-90s hits], booked New Year’s parties, bar mitzvahs, and weddings. Became despondent, ended up a salesman for mother’s little helpers, Desoxyn, methamphetamine in the rich suburbs of Detroit. Got hooked, straightened out, saved his marriage, became a drug counselor, a Little League manager, and a professed normal guy – with half a liver. • Jasper Blakely freely admits squandering his talent, but has no regrets, since squandering prevents “the man” from exploiting it. He taught rich kids how to ski, was accused of some improprieties [which he describes as jealousy revenge], married a forgiving – and pretty! – Christian woman and became – even he sees the humor – a Coor’s delivery truck driver. “I never drink the piss and stick to Left Hand Craft Beer, where I help around the place – don’t tell my employer. Fuck Coor’s! Our lab is our only kid and that’s cool.” They lived off the grid in a cabin they built themselves from a kit. He is now bald, he warned, in case any of us were planning to go to the 45th year reunion. • Peter Kaban went to Rutgers, screwed around, lived on a Kibbutz for a year, got an MBA in Global Financial Data Management at Georgetown. “We were good at big ideas,” he said, “and getting off on them, but we never learned the hammer and nail part.” He took an “ethically questionable” job in Flow Equity Derivative Strategies at a Financial Services giant [hint: beneficiary of a 2008 bail-out]. Drifted into tax shelter management for shell companies. Abandoned the industry. With a wife and three kids, he took a position at 30% of his previous salary at a Greenpeace-like NGO. Moonlighted as a stand-up comic, playing Mortie Soul, a Mort Sahl tribute act. He and his wife purchased an abandoned sailboat that they fixed up themselves. Took a year sabbatical to sail the Carribean where they discovered an uncharted island and got the right to name it. He can show us pictures of Yossarian Island, off the coast of Antigua, named after his literary hero from the anti-war novel Catch-22. • Stuart Lacy was committed to Syracuse Psychiatric after dropping 500 micrograms of LSD to prove to his girfriend that he too wanted to pursue the far reaches of ecstasy. It left him in a near-psychotic state for months – actually years, maybe forever. He eventually emerged, became a teetotaler, even against aspirin. Received a Masters from Ithaca College in the Poetics of Persuasion, wrote poetry – “the acid of literature” as his mentor, a Black Mountain Poet called it – to stop war, fund AIDS research, save affordable housing, block the theft of green space. Became an associate editor at the Library Journal, married his college sweetheart, a former orchestra triangle player, who once said: “The triangle is by no means a simple instrument to play.” Had two kids, but his reading poetry aloud at all hours, his unrelenting teetotaling evangelism, and recurring flashbacks led to the breakup of their marriage. He went on to work as a freelance taxman, switched to taxidermy – “the art of the dead appearing alive” – which he cannot explain, and he eventually settled down to become a high school English teacher. • I, Bertrand Planarien, attended the University of Wisconsin where I told people I had a cross-country scholarship and others that I had a poetry scholarship. Before school even began I had to sign for a registered letter at the local Post Office. It was my draft card, which I tore up into tiny pieces on the Post Office steps, dispersing the snippets between three garbage cans for security’s sake. And there I stood on the steps, feeling free, and yet, paranoid that a U.S. Government agent would somehow recognize me. I got a degree but never used my diploma, worked in factories in Flint, Michigan, cabdriver, foot messenger, office supply manager, proofreader, art management, failed journalist, failed everything – except dreamer. The dreams, too, have become less frequent, less vivid, less Hollywood. Moved to France, worked in forest management, as a house painter, bill poster, and handyman in Paris and wrote words against pretty much everything and, at some point, I began to count the words I’d written, gauge their power, how much of a fraction of a penny each word was worth – luckily, I stopped myself at around 13 million words ...

1 Comment

|

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed